My 2025 Baseball Hall of Fame Mock Ballot

The cases for and rankings of all 17 Cooperstown-worthy candidates

This year’s slate of Baseball Hall of Fame nominees comprise the most-interesting Cooperstown ballot class in recent memory. It’s not just that the 2025 candidates are particularly talented, though they are — in an election where voters can choose a maximum of 10 players, there are at least nine first-time-eligibles who are worth serious consideration, alongside the 11 holdovers from last year whom I consider deserving. It’s also that they raise several bigger questions about how we evaluate modern players' legacies.

The debates that have dominated Cooperstown discourse in recent years have grown stale. What do we do with steroid users? Should advanced stats like WAR have a role in the selection process? (Bonus points for punctuating your crotchety point with an Edwin Starr reference.) Is there room in the Hall for modern relievers? This year’s slate of candidates invites a new set of arguments. How do we adjust the durability expectations for starting pitchers when the greatest workhorse of my lifetime barely reaches the median for inductees’ innings? Do we really value catchers’ pitch-framing skills as much as contemporary models say we should? Having proven that the Baseball Writers' Association of America can be swayed towards initially underappreciated candidates — Tim Raines, Scott Rolen, Larry Walker — how will the analytics community choose their next cause célèbre among such a deep rookie class?

As an outspoken advocate of transparency in Cooperstown voting, it seems only fair that I hold myself to the same standard that I ask of others. So what follows is an in-depth explanation of how I would fill out my ballot, if I had one.

For the last two Hall of Fame elections, I worked through my (hypothetical) ballot by identifying the players whom I thought were deserving based purely on their athletic accomplishments, ranked them, then went down the list and removed candidates who flunked my moral standards until my 10 votes were fully allocated. I didn’t expect to change your mind on whether off-field scandals are relevant to player evaluation in an analysis like this, so I sought to focus on the baseball parts and let you apply your own ethical standards.

This year I’m tweaking the format. In an effort to highlight the aforementioned big-picture questions that span multiple players’ cases (and to hopefully rein in my own inflated word count), I took the additional step of clustering candidates by the core arguments behind their Cooperstown cases.

Before we dive into individual players, I’ll lay my cards on the table about my Hall of Fame philosophy. If you don’t share my evaluative framework, you probably won’t agree with my picks! But my hope is that, even if I can’t convince you that these players are worthy, you can at least follow my logic and understand where our perspectives may diverge.

On a basic level, I look for reasons to put players into the Hall of Fame rather than to keep them out. This is partly a function of my nostalgic completist mentality, but it’s mostly a reaction to how stingy the BBWAA voters were in my formative years. Take the 2013 election, in which not a single candidate was elected, though a decade later 10 of them (so far) have since been deemed worthy. I learned that a vibrant Hall of Fame requires us to make arguments for players, not against them.

It won’t surprise you that I gravitate towards modern sabermetrics for evaluating players, but I think we owe it to the athletes to consider their legacies in whatever terms are most favorable to them. Especially if they played in a time when a pitcher’s wins were seen as more important than their wins above replacement.

I believe that how good a player was and whether they belong in Cooperstown are somewhat different questions. I think being an all-time great at one facet of the game or heralding an evolution of league strategy should get you in even if you weren’t an MVP-caliber performer overall. For example, I am one of probably only three people in the world who would put Adam Dunn in the Hall of Fame. (The others I know of are Hal McCoy, the lone BBWAA voter who checked his name in 2020, and my friend Ed.) By conventional criteria, Dunn is nowhere close to the Cooperstown standard, especially since his celebrated bat came with some of the most atrocious defense in baseball history. But he is the greatest three-true-outcomes hitter of all time (we can talk about Aaron Judge after a couple thousand more at-bats), he was a harbinger of the contact-for-power trade that batters started accepting en masse shortly after he retired, and he is the only MLB player in recorded history to hit a home run into another state. That’s good enough for me.

The distinction between first- and subsequent-ballot Hall of Famers is silly. While a willingness to change one’s mind is good and healthy, I consider it a sign of either flippancy or smug process-story indulgence when voters decline to take candidates seriously until well into their 10-year eligibility windows — especially since the toll the process takes on borderline candidates’ stress levels is actuarially measurable. I was thrilled when Scott Rolen was elected on his sixth try after earning just 10 percent support on his first ballot, but I’m flummoxed by the opinion, implied by nearly two thirds of the BBWAA electorate, that a candidate who hadn’t played since 2012 somehow better between 2018 and 2023.

If my vote actually counted, I would probably triage my allotted 10 votes to prioritize players near the 75 percent threshold for induction or the 5 percent minimum to remain on the ballot, though it seems unduly obnoxious to pontificate on that when my picks are purely theoretical.

I do not consider cheating to be a dealbreaker for the Hall, unless the offense were so exceptional and game-breaking as to compromise the integrity of the sport. If Major League Baseball sees fit to welcome players who, say, test positive for performance-enhancing drugs back into its good graces after they serve their suspensions — to say nothing of those whose (alleged) doping predates collectively bargained prohibitions or is presumed but unproven — I see it as ahistorical and inappropriate to belatedly levy lifetime bans. I see it as fair to raise the bar slightly for known cheaters or to rank a clean player over a known cheater with similar numbers, but not to discount their achievements wholesale.

However, I take the opposite view of the off-field portion of Cooperstown’s so-called “character clause.” Allegations of domestic and sexual violence are distressingly common among Hall of Fame candidates. I have a blanket rule against voting for players who have been accused of such things. I know it is possible to appreciate an athlete’s accomplishments without endorsing them as a person. Still, the lines get blurred when bestowing an honor like Cooperstown induction, and making exceptions to your moral standards undermines your credibility when you choose to apply them.

Ultimately whether a player’s behavior is disqualifying comes down to who is hurt by them being honored. Adulating a steroid user is an embarrassing to the league, a reminder that the sports failed to coherently address the issue of performance-enhancing drugs for a century; celebrating an abuser may elicit far deeper pain among survivors of such experiences.

With all that said, there are 17 players on this year’s BBWAA ballot whom I believe had Cooperstown-worthy careers, plus four more honorable mentions who are worth serious consideration. Here they are, ranked by deservingness and grouped by broad criteria, along with (hopefully) concise explanations and footnotes listing their potentially relevant controversies. To be clear, there are several players listed below whom I believe should be disqualified for personal conduct, but first I want to engage with them based on their on-field merits.

Inner-circle greats

If you’re this deep into an article about the Hall of Fame, you don’t need me to tell you about Álex Rodríguez. But sometimes when a player has been in the public eye for as long as A-Rod has, you can forget just how good he was. He ranks fifth all time in home runs, fourth in RBI, and seventh in total bases. His three MVP awards and 10 Silver Sluggers each rank behind only Barry Bonds, and he did it while playing (two-time) Gold Glove defense at the second-hardest position on the field. He is comfortably the best infielder the sport has seen since integration, so when you adjust for quality of competition he is probably the greatest ever. There is no remotely serious argument that his on-field accomplishments are unworthy of the Hall.

Technically the same cannot be said for Manny Ramírez — there is a plausible, though myopic, argument that he gave too much of his offensive value back with his historically abysmal defense — but his bat was truly legendary. Ramírez’ .996 OPS is the best in history for right-handed hitter with at least as many plate appearances; throw in lefties and he trails only Bonds, Babe Ruth, and Ted Williams. His 29 postseason homers (on top of the 555 he hit in the regular season) are an MLB record. Aside from Bonds, he is the greatest hitter who is not enshrined in Cooperstown.

“You had to see him play” is usually what people say when they know a candidate they’re arguing for doesn’t have a good statistical argument. (You’ll see me do this a few paragraphs down.) Not so for Ichiro. The 10-time Gold Glover, three-time Silver Slugger, and oldest-debuting member of the MLB 3,000-hit club has an unimpeachable résumé, even without considering his time in Japan (with which he holds the record for most top-professional-level hits in the world). Yet his numbers don’t convey how magical he looked on the field. One of my most vivid baseball memories was when eight-year-old Lewie first saw him on TV, batting leadoff at the 2001 All-Star Game. “The skeptics said no, it wouldn’t work,” Joe Buck said of Ichiro’s playing style. Moments later, he beat out a grounder to first base, then slid into second on a steal almost before Mike Piazza’s throw passed the pitcher’s mound.

I’ve made the extended case for Billy Wagner before, and I will exercise some restraint in not rehashing it all again here. Suffice to say that unanimous inductee Mariano Rivera is the only reliever in baseball history to pitch as well as Wagner did for as long as he did it. On a pitch-by-pitch basis and relative to his era, Wagner has a legitimate argument as the most-dominant pitcher ever. We can debate what the standard ought to be for modern one-inning relievers, but wherever it is, Wagner is clearly above it.

There are two broad arguments for Andruw Jones. The first is that he was one of the most dynamic players in the game for at least a decade, and our lasting impressions of him as an athlete would be far better had he simply retired at age 30 rather than hang on through his precipitous physical decline. The second is that Jones is probably the single greatest defensive outfielder of all time, which for me is enough for the Hall no matter what he did as a hitter. Which was a lot: including the playoffs and his time in Japan (if it’s fair game for Ichiro…), he came just six homers shy of reaching 500.

My pet theory is that Chase Utley is ironically underrated because he is so beloved: the industry did not properly value his skillset — strong but not monstrous power, efficient baserunning without blazing speed, quietly exceptional defense — in his heyday, and he sold his late-career image as a wily veteran so well that the industry has collectively forgotten to reevaluate his prime. So here’s some quick context. From 2005-09, Utley earned 7+ fWAR five years in a row. Only 13 other hitters in MLB history have achieved such a run of uninterrupted excellence: Henry Aaron, Wade Boggs, Barry Bonds, Ty Cobb, Lou Gehrig, Charlie Gehringer, Rogers Hornsby, Willie Mays, Joe Morgan, Albert Pujols, Babe Ruth, Mike Trout, and Honus Wagner. These legends of the game are the company Utley keeps.

Hindsight is 20-20

8. Carlos Beltrán4

11. Bobby Abreu

When the voters of the BBWAA sit down with their ballots, they can take one of two broad philosophical approaches. The first is to evaluate the candidates as they remember them. Did you feel like you were watching a Hall of Famer? The second is to reconsider the players’ legacies through new lenses. The latter mindset is both fairer and more fun.

I don’t remember people talking about Carlos Beltrán as Cooperstown-bound while he was in his prime, but we ought to have been. He was a true five-tool player who earned three Gold Gloves, two Silver Sluggers, and nine All-Star nods. Only four hitters in MLB history have exceeded both his 435 homers and his 312 steals, and the only ones with more 20-20 seasons than Beltrán’s seven are either named Bonds or the subject of the next paragraph. His 1.021 playoff OPS is the best in history among batters with at least 185 PA. He was one of the best players of his generation, whether we knew it at the time or not.

That applies even more so to Abreu, who certainly was not seen as a future Hall of Famer in his heyday, but is exactly the kind of player who warrants reappraisal. He was ahead of his time in his batting approach, becoming an on-base machine before taking walks was cool. Without selling his peak short — he had the fifth-highest fWAR in baseball from 1998-2004 — his signature trait was his consistency, which is easier to appreciate in retrospect. Abreu is the only player outside the Bonds family to go 20-20 nine times, or to reach 15-15 in 10 consecutive seasons. Only six other hitters have earned an .815 OPS in at least 585 PAs for twelve straight years: Henry Aaron, Lou Gehrig, Willie Mays, Stan Musial, Albert Pujols, and Paul Waner. Impressive peers.

A pitch for new standards

Now that most of the Steroid Era’s most polarizing figures have fallen off the ballot, the biggest question facing Cooperstown voters today is what to do with starting pitchers. A full MLB starter’s workload is simply lower than it used to be, as pitchers throw with more effort and teams fret about pitch counts and times through the order. This means they pitch fewer innings, which in turn reduces their opportunities to accumulate wins, strikeouts, and WAR. Yet the voters have not adjusted. The recent trend of clearly Hall-worthy starters getting snubbed — Kevin Brown, David Cone, Johan Santana — will only accelerate as we get deeper into the Pitch Count Era.

Which brings us to a fork in the road. We can continue applying historical standards to new candidates, knowing they are functionally impossible for contemporary players to reach. Or we can take a step back and acknowledge that elite starting pitching in this generation simply manifests in different ways — lesser, if you must — than it did in the past. I am firmly in the latter camp, which I see as the logical extension of my pro-reliever bent. I don’t know exactly where the line should be drawn for modern starters, but in the interest of preserving positional balance, it’s probably a step and a half lower than you think.

With that in mind, CC Sabathia is a no-doubter. The six-time All-Star and five-time Top 5 Cy Young finisher was an institution of the game. His 251 wins, 3577.1 innings, and 66.5 fWAR are in line with Cooperstown standards, but perhaps more importantly, they’re feats we may never see again. If Sabathia is not a Hall of Famer, we should just dispense with the kayfabe and stop including pitchers on the ballot at all.

If we’re looking for reasons to put starters in, then having been universally acknowledged as one of the most-dominant aces in baseball for a several-year stretch should be more than enough for admission to Cooperstown. That’s Félix Hernández. From 2009 to 2014, he was tied with Clayton Kershaw for the highest fWAR among starting pitchers (37.2) and ranked second in the league with a 2.73 ERA, winning one Cy Young and finishing in the top two thrice. You can deduct points for pitching in offense-chilling T-Mobile Park, but you should add them back in recognition of the iconic “King’s Court” fan environment he inspired there.

Mark Buehrle and Andy Pettitte’s cases are extremely similar: two crafty lefties with long careers and underrated peaks, separated by just four points of ERA and 32.2 innings. Pettitte’s best year was better. Buehrle’s peak was longer. Pettitte holds the record for most postseasons wins and innings. Buehrle won four Gold Gloves. Tie goes to the one who is not known to have taken human growth hormone — a performance judgment, not a moral one — but both had Cooperstown-worthy careers.

Fittingly, closing out this cohort brings us back to why I am so open-minded about starting pitchers: it is a necessary counterbalance to my philosophy for relievers. The bar for Cooperstown ought to be far higher for pitchers who throw one inning at a time instead of six. But their skillsets are not interchangeable, and comparing every bullpen arm to Mariano Rivera is as unrealistic a standard as expecting first basemen to be as legendary as Lou Gehrig. A plurality of MLB players are relief pitchers, and I firmly believe that there is room in the Hall of Fame for a handful of the most dominant arms of each generation.

Francisco Rodríguez fits the bill. You may know that he holds the single-season saves record (62) and ranks sixth on the all-time list (437). Had he called it quits a year earlier (instead of getting shelled for 23 runs in 25.1 innings in his farewell tour), he also would have retired with the highest career strikeout rate (28.7 percent) among pitchers with at least as many innings, while trailing only Nolan Ryan in batting average against (.202) and ranking ninth in ERA (2.73) over the preceding century. He earned three top-four Cy Young finishes and a top-six MVP ranking out of the bullpen, and had one of the greatest reliever playoff performances ever as a rookie during the then-Anaheim Angels’ 2002 championship run. Christened with one of the best nicknames in all of sports, K-Rod helped make the modern closer cool.

Reframing catcher value

13. Russell Martin

16. Brian McCann7

It’s particularly hard for a catcher to make the Hall of Fame. The grueling nature of the position means players need more time off and the aging curves are steeper. If they move out from behind the plate later in their careers, it’s usually to first base, where the bar for hitters suddenly gets much higher. Joe Mauer’s surprising (but welcome) first-ballot selection in 2024 may portend a shift in how the voters evaluate catchers. This year we’ll find out for sure.

In the span of under two decades, the sabermetric community went from rolling their eyes at the belief that catchers could make their pitchers meaningfully more effective to proselytizing it. The ability to quantify pitch-framing, the art of receiving pitches while creating the subtle visual cues of a strike for the umpire, revolutionized our understanding of how catchers generate value. (It’s also a revealing illustration of how MLB condoning and even endorsing a strategy that could be considered cheating leads to it being understood as legal — an allegory that ought to inform how we consider players accused of using PEDs.) While the specific ratings vary across models and granularities of input data, the delta between the best and worst framers in the league is on the order of multiple WAR per year. This understanding has fundamentally altered how teams acquire, develop, and value catchers. And if the industry believes this as much as they say they do, it should be a major consideration for catchers’ Cooperstown cases, too.

There is no single source-truth for framing among the various public-facing models, and even if there were, the earliest ratings I’m aware of go back only to 1988. Still, so far as I can tell, the three most-readily available metrics (FanGraphs’ and both the current and prior versions of Baseball Prospectus’) all agree on one thing: Russell Martin is the best framer in recorded baseball history. It’s an admittedly attenuated bit of hyperbole, but once again I believe that having a plausible case as the greatest at a given skill is enough to get into the Hall. What’s more, his defense was so exceptional that, despite a career slugging percentage below .400, Martin actually has more fWAR than Mauer (who had 20 percent more plate appearances in which to accumulate value). Take the specific numbers with a grain of salt, but if you believe in the importance of framing, he is clearly over the line.

It follows that Brian McCann should be in, too. His case is quite similar to Martin’s: not nearly good enough for long enough by conventional criteria, but so skilled at stealing strikes that it vaults him from merely padding out the ballot numbers to worthy of enshrinement. The main difference between their candidacies is that McCann was a much better hitter — his peak OPS (.961) was even better than Andruw Jones’ (.922). The flipside is that McCann was merely an elite framer, not the possible best ever. While I value Martin’s superlative a little more, their overall values are close enough that I don’t see how you could argue for one but not the other.

All you need is glove

10. Omar Vizquel8

12. Ben Zobrist

I said at the start that there should be a place in Cooperstown for players like Adam Dunn, who did not play at an all-around elite level, but who exhibited excellence in a single aspect of the sport or helped usher in an evolution in how the game is played. This year’s Hall of Fame ballot features two candidates who fit the mold — even though they are very, very different than the Big Donkey.

You had to see Omar Vizquel play. (I told you I would use that line!) He was quite simply the best defensive shortstop I’ve ever seen. What I remember most are not the web gems (though they were numerous) but how fluidly and gracefully he moved even on routine plays. How he made a ballet out of turning two. If we must talk numbers, Brooks Robinson and Ozzie Smith are the only infielders in history with more Gold Gloves than Vizquel’s 11 — a fitting reflection of where I’d argue he ranks among the sport’s greatest defenders. To be clear, when I say Vizquel’s glove makes him Hall-worthy, I’m not arguing that his overall value was on par with that of the other hitters on this list despite his shortcomings as a hitter. My belief is that a glove as special as Vizquel’s ought to be immortalized regardless of what he did in the batter’s box.

For most of baseball history, playing multiple positions carried a stigma. With some exceptions (I was fascinated with Ryan Freel and Mark McLemore when I was a kid) it was a sign that the player wasn’t good enough to hold down an everyday lineup spot. Then came Ben Zobrist. His breakout 2009 season was remarkable not just for the improbability of an unheralded 28-year-old suddenly playing at an MVP level, but of doing it while playing seven different positions. For another decade thereafter, Zobrist made versatility cool — and became the archetype for a new vision of position-less baseball. As recently as nine years ago, when the Chicago Cubs signed him to a four-year contract, I remember people being flummoxed by giving $56 million to a so-called “utility man.” Now there’s a special Gold Glove for multi-position players, and even as established a superstar as Mookie Betts routinely moves all over the diamond. Zobrist was a pioneer of modern baseball strategy, and for that he has earned a place in Cooperstown even if the rest of his résumé falls short.

Honorable mentions

Ian Kinsler

Dustin Pedroia

Troy Tulowitzki

David Wright

As I weighed all the candidates on this year’s ballot, there were four players whom I couldn’t quite justify calling Hall-worthy, but I also felt bad leaving off. In a world where candidates so often gain support over time, I could see myself being swayed to them in the future, and I’m rooting for them to reach the 5 percent threshold to stay on the ballot so we can reconsider them in 2026.

Ian Kinsler is the definition of a borderline candidate. Per Adam Darowski’s (sadly now defunct) Hall Rating, where 100 points is the threshold for Cooperstown, Kinsler comes in at 99.5. He was really good for a long time — he had nine seasons of 4+ bWAR — but his career numbers are underwhelming in the context of Cooperstown. He was underrated in his day, though even in hindsight he was never in the conversation as one of the best players in the game. If you count Zobrist, you could argue that Kinsler isn’t even a top-three second baseman on this ballot. Maybe we can talk after Utley gets in.

At the other end of the spectrum was Troy Tulowitzki. In his prime, you could have made the case that Tulo was one of the best players in the game when he was healthy. But injuries took a severe toll on his career. He averaged just 92 games a year and retired at age 34. There is narrative power in such a what if: he had a 1.035 OPS in 2014 before hip surgery ended his season in August, then declined to just a .752 OPS for the rest of his career. It was injury, not ability, that derailed his clear Cooperstown track. But his qualifications are too theoretical for me to justify them.

The cases for Dustin Pedroia and David Wright are effectively the same: true superstars, synonymous with the respective teams for whom they played their entire careers, cut down prematurely by insurmountable recurring injuries. It feels strange to leave them off my ballot — my gut reaction was that they are both Hall of Famers — but if being a fan favorite is worth that many bonus points, you have to start talking about players like Jimmy Rollins, too.

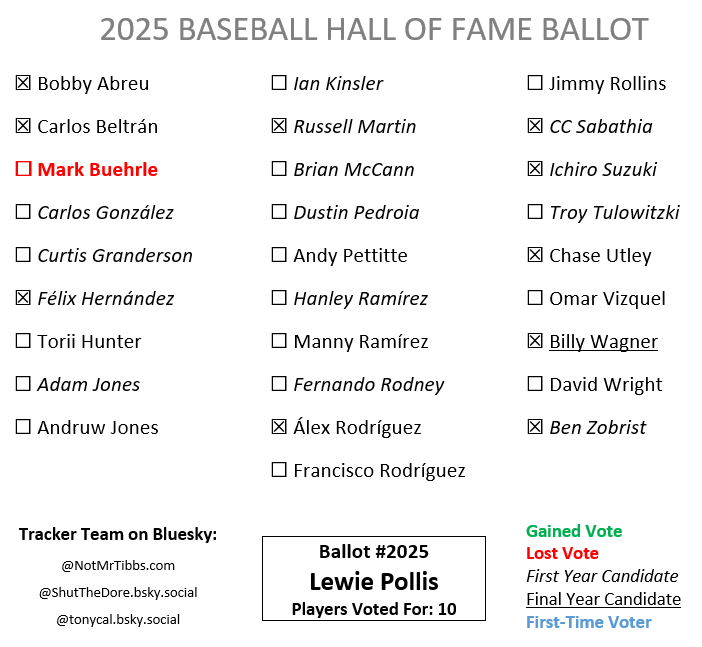

Of the 17 worthy candidates I have listed, I’m disqualifying Andruw Jones, Manny Ramírez, Francisco Rodríguez, and Omar Vizquel because of their respective allegations of domestic violence. That gets us to 13 players, which I will pare down from the bottom of the rankings by dropping Mark Buehrle (who technically counts as a dropped vote from last year, though the snub is only for space reasons), Brian McCann, and Andy Pettitte. So my 2025 Hall of Fame votes go to:

Bobby Abreu

Carlos Beltrán

Félix Hernández

Russell Martin

Alex Rodríguez

CC Sabathia

Ichiro Suzuki

Chase Utley

Billy Wagner

Ben Zobrist

Ballot-tracking maven Ryan Thibodaux kindly turned my picks into an official BBHOF Tracker image:

Those are my Cooperstown picks. Who are yours?

Rodriguez was suspended for the entire 2014 season for his role in the Biogenesis doping scandal, and has admitted to using banned substances from 2001 to 2003

Ramírez was arrested for and charged with domestic violence in 2011.

Jones was arrested for a domestic violence incident in 2012 and pled guilty in court.

Beltrán was an alleged architect of the Houston Astros’ illegal sign-stealing system.

Pettitte has admitted to using human growth hormone on multiple occasions during his career.

Rodríguez pled guilty to attempted assault of his girlfriend’s father in 2010, and was charged with domestic abuse in 2012.

McCann was an Astros hitter while they ran their illegal sign-stealing scheme in 2017, though he reportedly disapproved of it.

Vizquel was accused of domestic violence in 2020 and of sexual harassment and bullying in 2021.

Utley must get in.