Cooperstown's Votes of No Confidence

The historical impact of the BBWAA's secret ballots on the Hall of Fame

It was January 2011 and I had far too much time to kill before the end of my college winter break. As was my wont, I fell into a rabbit hole of baseball data. The results of the annual Baseball Hall of Fame vote had just been released, and I found some conspicuous differences between the grassroots tallies of the ballots that were revealed before the election (essentially a virtual exit poll) and the official totals once the secret ballots (then the vast majority of submissions) were counted. In other words, those who voted anonymously made different choices — and, in my opinion, less-reasonable ones — than their peers who put their names on their ballots. So I wrote about it with all the righteous indignation of an 18-year-old who had nothing better to do.

Because I am an obsessive completist, this phenomenon became my beat as a baseball blogger. I noticed and complained when anonymous voters’ choices diverged from their more-transparent peers’ again in 2012. And again in 2013, and in 2014, and in 2015. Then I stopped writing about baseball for a while. By the time I returned to the subject this past January, the culture had shifted such that the majority of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America’s voters now voluntarily share their ballots with the public. But a significant minority of holdouts remained, and these secretive writers’ votes followed familiar patterns.

These analyses each suffered from two significant flaws (besides my adolescent sanctimony). First, I was looking at only one election at a time, so the samples were too small to convince non-sympathetic audiences.1 The second was waiting to complain until after the results were announced and it was too late to change anyone’s mind. After all, if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.

So this time I’m taking a different tack. As I write this, it is November: the 2024 Hall of Fame nominees were unveiled last week, and BBWAA members are starting to get their ballots in the mail. As the writers are making up their minds about how to vote (in more ways than one), I dove into the historical data for public and private ballots to get a big-picture view of how anonymity impacts the Cooperstown selection process, which as far as I know has never been done before. It is my hope that the more-relevant timing and larger dataset help convince more voters to share their selections — because I am more convinced than ever that secret ballots are distorting the Hall of Fame election results.

In our democratic political system, voting is a right, not a privilege. At least in theory, it is a universal right extended to all adult citizens. The secret ballot is an important tool to prevent bribery and harassment based on how people vote. No matter how informed you are, what issues you prioritize, or from whence you derive your ideological worldview, your dual rights to influence the government and maintain privacy while you do so are (supposed to be) inalienable.

By contrast, voting for the Baseball Hall of Fame is a privilege, not a right. The Cooperstown election process is more technocratic than democratic. Only 400 or so members of the Baseball Writers Association of America will receive ballots this month. The qualifications to get one — at least a decade of recent experience covering MLB for an accredited publication — ensure an electorate where everyone has both insider-level knowledge of the game and an extensive track record of disseminating information and analysis to the public. Absent discriminatory inclusion policies, the conditions for participation in what is essentially a glorified organizational membership survey have nothing to do with civil rights.

Therefore, just as the secret ballot does not apply to floor votes in Congress, privacy is less important for Hall of Fame electors than for laypeople going to the polls. The BBWAA clearly understands this, as they reveal each voter’s full ranked-choice ballot for other awards like the Most Valuable Player and Cy Young. They also voted overwhelmingly to make all Cooperstown votes public in 2016 — with 90 percent in favor, open ballots got more support than any actual candidate did that year — but the Hall of Fame’s Board of Directors overruled them. So secret ballots remain to this day.

For consistency and ease of data-mapping, the forthcoming analysis is based on the BBWAA’s official releases, which include selected individual ballots dating back to 2012.2 It started out as a few dozen voters revealing their picks this way, then grew into a majority of the electorate by 2016. Participation has plateaued around 80 percent for the last five years.

The BBWAA’s numbers actually undercount the number of writers who published their ballots. The famous BBHOF Tracker, which Friend of The Lewsletter Ryan Thibodaux has maintained for over a decade and includes @leokitty’s data going back to 2009, has better coverage, especially the further back you go. This means many voters have written or tweeted about their ballots in the past but did not authorize them to be officially listed by the BBWAA. (The jump to the current equilibrium level in 2019 corresponds to the current opt-in/out checkboxes being added to the ballot itself.) This is a significant caveat for the forthcoming analysis, though on the flipside it means that any differences we see between public and secret ballots are underestimates, since many of the former are lumped in with the latter.

And there are differences.

Some natural variation between two groups of voters is normal, to the point where we would expect to see a handful of player discrepancies achieve common measures of statistical significance based on random chance alone. (If the full population of voters is divided exactly 50/50, the chances of 100 random ballots yielding a mandate of 60 percent or more in either direction are double the odds of rolling snake eyes.) How do we know that the differences in public and private votes are not mere statistical noise? There are two high-level trends that I find convincing. First, those who reveal their choices are more generous with their votes than those who don’t, with a median yearly discrepancy of more than a player per ballot over the last decade.

Second, the differences in how the two groups of voters evaluate players are consistent over time. On the following chart, the x-axis shows how much support players got on secret ballots relative to public votes — i.e., their vote percentage each candidate got from anonymous voters minus their vote percentage from named ballots. Negative indicates they did better on open ballots, positive means more support from secret ballots, and higher-magnitude numbers reflect larger spreads. The y-axis displays the same metric for the following year. (Players on the ballot for n years in this timespan are represented n - 1 times.) A simple linear correlation yields an R-squared over 0.7, with the trendline coming awfully close to a 45º angle.

To be clear, these patterns suggest a correlation between ballot transparency and voting philosophies, not causation. Ballot-sharing culture is driven by social media, so the choice to reveal one’s vote could be an instrument for generational differences in analyzing the game rather than a cause of diverging behavior. We would dismiss this potential selection bias at our own peril. On the other hand, these factors were probably more salient when ballot-tracking was a niche nerdy hobby rather than an official BBWAA initiative, and while Cooperstown voters enjoyed the privilege for life (changed in 2015 to exclude writers more than a decade into retirement). Plus, approving mandatory open ballots with 90 percent in favor surely indicated a broad pro-transparency coalition within the BBWAA.

Whatever the root cause, there are some clear patterns in which players over- and under-perform on secret ballots. Let’s look at the 10 biggest public-private vote disparities of the last 12 elections in each direction. Compare those who seemingly benefited the most from anonymous voting:

With the players who did better on named ballots:

In one corner, we have Fred McGriff, Jack Morris, Lee Smith, Omar Vizquel, and Bernie Williams. McGriff, Morris, and Smith are enshrined in Cooperstown (McGriff and Smith deservedly), and I diverge from most sabermetrically inclined fans in that I think Vizquel’s on-field accomplishments merit inclusion too. You’re reading Williams’ line correctly: none of the 55 writers who voted for him in 2012 published their ballots through the BBWAA (though at least three did so elsewhere).

But when you put those names up against the incredible lineup of Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Scott Rolen, Curt Schilling, and Larry Walker? It’s not even close. Leaving aside the their respective off-field controversies — we’ll get to that — whoever the weakest link of the latter group is (probably Rolen) would be the best player in the former. My go-to somewhat-objective metric for evaluating Cooperstown worthiness is Adam Darowski’s Hall Rating. The first fivesome’s average Hall Rating is 79, with none of the players reaching the 100 threshold for enshrinement. (McGriff comes closest, at 95.) The second quintet’s average is an amazing 225, with each ranking as not just fit for Cooperstown but as one of the 100 best players in MLB history.

This is as good a time as any to address the elephants in the room: the many high-profile scandals surrounding players on recent ballots.3 Vizquel has been accused of both domestic violence and sexual harassment, which has (very reasonably) redefined his image around the game. His disproportionate support from non-public voters over the last few years, including the largest secret-ballot advantage on record in the first election after the allegations surfaced, has inspired a narrative that Vizquel voters are taking advantage of their anonymity to support a man with whom they would be ashamed to have their names attached. Meanwhile, voters’ main objections to Bonds and Clemens, both inner-circle greats and among the most-accomplished players of all time, are their notorious use of PEDs. Whether because younger voters who are more likely to share their ballots are also more open to immortalizing dopers, or because those who think PEDs are dealbreakers for Cooperstown know their argument is ahistorical, Bonds and Clemens routinely came in lower than the early ballot-tracking data would indicate in their 10 years on the ballot.

The reality is more complicated. Andy Pettitte, who not only admitted to using human growth hormone but has taken a ridiculously sanctimonious tone towards other dopers, routinely gets more support on secret ballots than named ones. Infamous cheaters Alex Rodriguez (9 percent more support from anonymous voters in 2022) and Manny Ramírez (7 percent in 2019) have also done better with the private caucus. On the other hand, Bonds and Clemens have been accused of domestic abuse and child-grooming, respectively, which complicates the notion that public-facing voters apply stricter moral standards. PEDs may be their most-salient scandals in the public zeitgeist, but surely the veteran journalists of the electorate should be aware of these incidents. Among still-eligible candidates, domestic violence offender Andruw Jones has done better on published ballots over the last few years, including a 19-percent differential in 2023. And while the 2016 BBWAA election predated many of the worst controversies that spring to mind when you read Schilling’s name, he had just been suspended by ESPN for comparing Muslims to Nazis, and he maintained conspicuously disproportionate support on named ballots through the end of his eligibility window even as his subsequent scandals mounted.

In short, I do not see an obvious pattern for how off-field issues impact the salience of secret ballots — or at least, the inconsistency with which athletes suffer reputational harm for their scandals confounds generalizability to Cooperstown consideration. The same cannot be said for how anonymous voting affects the other major narrative juxtaposition between Vizquel and Bonds: quality of performance. However you feel about Wins Above Replacement as a tool for baseball analysis, at the very least its leaderboards are highly correlated with popular notions of how players stack up, and reasonable starting points for comparing players’ careers.4 So a relationship between public-private voting differentials and WAR would be telling.5 To wit:

These twelve years of election results include over 200 instances of a player receiving at least 2 percent support (a quick filter for players whom the writers considered to be remotely serious candidates).6 Extrapolating from that data, for every 6 additional WAR a player earns in their career, they lose 1 percent support from secret ballots relative to published ones. The sample size plummets if you limit the analysis to each player’s most-recent election (so e.g. Bonds and Clemens don’t represent 10 different datapoints each), but the relationship is nearly identical. Or, if using straight WAR is too facile for your taste, we see the same trend when comparing the vote deltas to Jay Jaffe’s JAWS, which balances candidates’ career production with their peak value:

You can probably make out Rolen’s foxhole at the bottom of these graphs and find Bonds and Clemens’ columns on the right. The point my eye keeps getting drawn to is on the lower left. That’s Billy Wagner, who heads into the 2024 BBWAA election with the largest previous public-private vote discrepancy of any player left on the ballot. Wagner has the second-lowest JAWS rating of any candidate to meet the 5 percent stay-on-the-ballot threshold in over a decade. In other words, he is not the type of player we would expect to do worse on anonymous ballots if the differences were generational rather than causal — strong as his case is, voting for a reliever but not, say, A-Rod does not comport with sabermetric WARthodoxy. It also leads us to the single best predictor I could identify (outside of the prior year’s delta) for the discrepancy between a player’s public and private support:

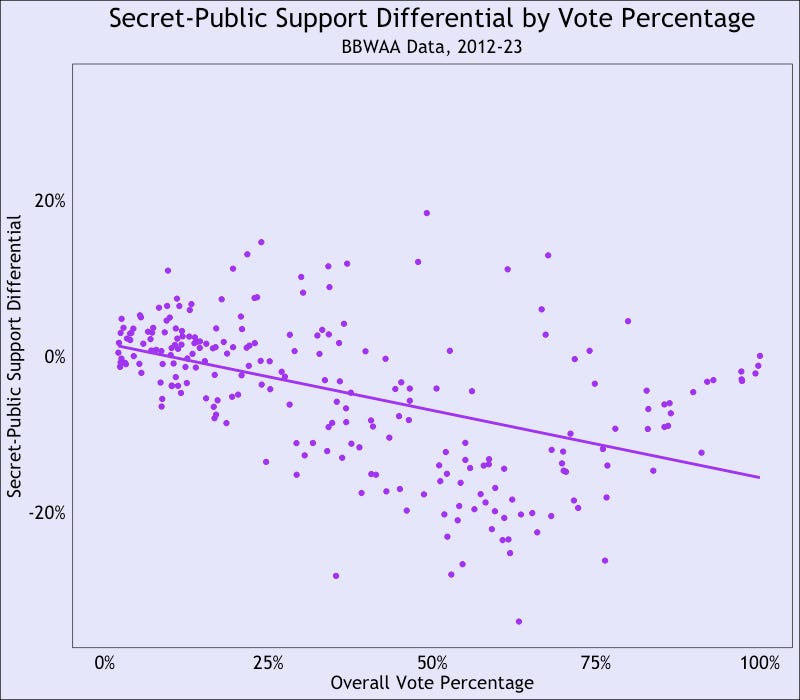

The relationship between a player’s overall vote total and the size of their support splits necessarily confounds linearity. (When a candidate approaches 100 percent of the vote, by definition that means there were no pockets of voters with whom they fared significantly worse than others.) The trend is unmistakable regardless. The more votes a player gets, the more their relative support on secret ballots wanes. Of the 25 players since 2012 to reach the requisite 75 percent for enshrinement, only one (Trevor Hoffman) saw his support go up when the private votes were counted. The linear trend indicates candidates lose a point of anonymous support compared to public ballots for every 6 percent of the vote they get overall. In other words, there is a direct and clear relationship between how worthy a candidate is — not according to a black-box formula or some guy in his basement, but the BBWAA voters themselves — and how much they are hurt by secret voting.

In the spirit of constructive communication, I am making a concerted effort to present these findings as straightforwardly and nonjudgmentally as I can. Yet the conclusion from this last chart is inescapable. Not only do those who cast secret ballots vote differently than those who publish their choices. They vote worse.

If you accept that anonymity is at least partly a true causal factor in the discrepancies between published and secret ballots, the impact is felt not just in the vote totals but on the binary results. There are seven instances since 2013 of a player exceeding the 75 percent threshold for induction among public votes but falling short once the anonymous ballots came in: Craig Biggio in 2013 and 2014, Mike Piazza in 2014 and 2015, Jeff Bagwell in 2016, Edgar Martinez in 2018, and Todd Helton in 2023. The first four all got in eventually and Helton is likely to join them next year. But why make them wait? Especially when the stress of a near-miss election is so great that it makes a measurable impact on a candidate’s life expectancy?

This on top of some other close calls. Rolen’s comfortable 82 percent support on public ballots this year fell to a nail-biting 76 percent once the anonymous votes, from whence he got just 56 percent, were counted. Mike Mussina, David Ortiz, Iván Rodriguez, and Larry Walker each received 80 percent of the vote from writers who shared their ballots, buoying them above 75 percent when they were snubbed by their more-secretive peers (from whom their support ranged from 62 percent and 71 percent). At the other end of the spectrum, where candidates need at least 5 percent support to remain on the ballot next time, Bobby Abreu relied on public voters each year from 2020-22 (when he got between 6 and 9 percent overall but just 4 percent from secret ballots) before finding some helium (15 percent overall) in 2023. Likewise for the underrated Tim Hudson, who cleared the bar by a single vote in his first try in 2021 before falling to 3 percent on a more-crowded ballot in 2022.

As far as I can tell, the converse — a player reaching the threshold from secret ballots but not from published ones — has never occurred at the 75 percent enshrinement level, though it happens about once a year for the 5 percent required to get another shot. Carlos Delgado, Jason Giambi, Paul Konerko, Joe Nathan, Jorge Posada, and Alfonso Soriano were all one-and-dones on the ballot, but each got 5 percent or more from anonymous voters. Nomar Garciaparra and Bernie Williams (the aforementioned year when he got zero votes from BBWAA-published ballots) had enough mysterious benefactors to stay on the ballot after their respective first tries, though both fell off the next year. The private caucus also defied their transparent peers and kept hope alive for Torii Hunter on his second ballot, Sammy Sosa on his third try, and Don Mattingly on his 14th attempt.7

This bloc’s disproportionate support for marginal candidates could actually make strategic sense. Voters are allotted a maximum of 10 selections per ballot, and most years there are more worthy players than that. Helping a longshot candidate whom you believe is worthy get 5 percent to stay on the ballot arguably makes more of an impact than boosting a more-popular pick from 24 percent to 25 percent or 54 percent to 55 percent, and maybe even taking a player on the cusp of induction from 74 percent to 75 percent (since they will probably get in eventually anyway).

Yet this reasoning falls apart when you consider that anonymous voters choose fewer players (as shown in the chart above), so ballot space is not the issue; and that these candidates would benefit the most from public stumping and vote-coordination if their supporters really believe in them. Further, the aforementioned players are hardly causes célèbres as unfair snubs, like Kenny Lofton or Johan Santana. Of the 11 names listed in the last paragraph, only one (Sosa) would have made my ballot. The upshot is that anonymously voting for guys like Konerko and Soriano, who have no shot at Cooperstown, while all-time greats like Wagner and Helton are left out in the cold doesn’t read like principled disagreement. It comes across as not taking your vote seriously since you know you won’t get any flack for it.

I write this essay knowing that, when I hit Publish, it will go directly to the inboxes of several voting members of the BBWAA. If you’re one of them, odds are you are part of the majority of writers who share your ballots with the world, so thank you for your transparency. Maybe you could you pass this message along to some of your coyer friends, and ask them to model the behavior the BBWAA has sought to codify?

If this writing finds its way to a voter who doesn’t share their selections, I’m not accusing you of malfeasance or negligence. You might not vote differently because of your anonymity. Maybe your ballot looks the same as mine would. (That’s my point; I have no way of knowing.) But I would ask you to take the coming weeks to rethink that choice as you are considering your ballot.

Consider the importance of the Hall of Fame’s reputation. The political nature of the Cooperstown selection process is not new, but it has received increased attention at a time when fans are more attuned to voting trends. Institutions becoming vulnerable to bad-faith conspiracy-mongering after failing to cultivate their assumed credibility has been a common theme across our society in recent years. The existence of a divergence between public and anonymous votes, however benign the cause, is worth addressing. So is the conflict of interest of a journalist not disclosing their role in shaping a news event they will write about. Sunlight is the best disinfectant.

Diversity of opinion is also good for the game. Many have bemoaned the homogeneity of modern baseball thought, with advances in analytics and strategic optimization leading to less action in games and greater leaguewide conformity. If the disparities in how anonymous voters’ submissions reflect genuinely different approaches to player analysis, any of the veteran sportswriters holding a Hall of Fame ballot should be qualified to articulate that. Recent inductees Tim Raines, Edgar Martinez, and Larry Walker were all elected thanks to fan campaigns in support of the candidates who had long been unjustly snubbed. Scott Rolen got just 10 percent of the vote in his first time on the ballot, and it is a credit to the electorate’s open-mindedness that he was elected five years later.8 That’s the same vote percentage Bernie Williams got from his mysterious benefactors in 2012. If his initial supporters had been as vocal as Rolen’s, would his bust now adorn the Plaque Gallery too?

I understand not wanting to potentially get yelled at on the internet for your votes. The widespread outrage at Lawrence Rocca and especially Ken Gurnick after they left Greg Maddux off their ballots in 2014 serves as a cautionary tale. Of course an easy way to avoid incurring social media’s wrath is to not snub one of the arguable 10 best pitchers of all time. At least they had the guts to put their names on their ballots, unlike the 14 other anti-Maddux voters whose identities remain a mystery. The same goes for the secretive souls who left Ken Griffey Jr. and Derek Jeter, who both got unanimous support among public votes, off their ballots. If you are part of a selective group chosen for their professional expertise in baseball analysis and mass communication and you cannot make a convincing argument for your Cooperstown choices, that doesn’t mean you should keep your picks anonymous. It means you voted wrong.

The official rules for the Hall of Fame selection process specify six criteria by which to evaluate candidates: “the player's record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played.” The categories are vague and largely overlapping, but it’s notable that voters are instructed to focus as much on personal decency as athletic accolades. (Varying interpretations of the “character clause,” as the consideration of off-field conduct is commonly referred to, are ultimately the driving force behind many of the most-contentious contemporary Cooperstown debates.) I submit that, in vetoing the BBWAA’s decision to make all ballots public, the Hall of Fame’s leadership acted against its own professed principles. As the data presented here show, secret ballots are detrimental to the integrity and sportsmanship of the selection process.

Perhaps someday the stewards of the Hall will have a change of heart. In the meantime, I urge all voting members of the BBWAA to lead by example and open your ballots to the world. It is a sacred privilege to admit or deny entry into Cooperstown, and the last dozen elections show that secret ballots threaten the integrity of the process. Please don’t balk at this responsibility.

The last five elections have included an average of 30 candidates, and typically only around two dozen receive even a single vote.

I’m sympathetic to the idea that revealing ballots en masse before the results are released takes some of the magic out of the announcement. That’s not an issue for ballots released this way.

To put my cards on the table: I do not think those who used performance-enhancing drugs should be disqualified from the Hall of Fame, and while I respect those who can compartmentalize on-field accolades from off-field scandals, I would not vote for someone accused of sexual or domestic violence.

In short, WAR is an estimate of how many fewer games a team would have won if the player in question disappeared and the team had plugged a minor-leaguer or waiver claim in their place. A more-thorough summary can be found here.

Thanks to the good folks at Sports-Reference, from whom I scraped WAR and JAWS data.

I’m not saying Lance Berkman and David Wells didn’t have cases for Cooperstown. I am saying they got fewer votes than Sandy Alomar Jr.

The rules have since changed to limit ballot eligibility to 10 years, after which players can still be considered by more-selective Era Committees.

On the flipside, it’s strange that the majority opinion of the BBWAA is that he somehow was more qualified 10 years after he retired than he was five years after he hung up his cleats.