The 2023 Baseball Hall of Fame Ballot, Part II: How I Would Vote

The fourteen Cooperstown-worthy players, ranked. Apply your own moral limits

That special time of year is already here. Not the holidays — Hall of Fame debate season! I am not a member of the Baseball Writers Association of America, let alone one tenured long enough to vote for the Hall of Fame, but not having a practical need for strong opinions has never stopped me before. So since I am at liberty to write about Cooperstown candidates for the first time in eight years, I am fully availing myself of the opportunity to do so. (You’ll know what I mean when you see how long this post is.)

To quickly summarize how the Hall of Fame voting process works: Players who spent at least a decade in the Major Leagues can appear on the ballot five years after their last game. The 400 or so veteran sportswriters from the BBWAA who comprise the electorate can each vote for up to 10 candidates. If a player is named on 75% of submitted ballots, he gets a plaque in Cooperstown the following summer. If he falls short of election but receives at least 5% support, he stays on the ballot the following year, up to a maximum of 10 tries. The nonintuitive quirks of this process include players being expected to consolidate support over the years, long after their careers ended; voters who believe there are more than 10 worthy candidates on the ballot triaging support to players whom they expect to be close to the 5% or 75% thresholds; and writers taking advantage of the secret ballots to snub worthy players anonymously.

Last week, I wrote at length about what I consider and prioritize when evaluating players in the context of Cooperstown. If you’re not a hardcore fan and you’re interested in learning more about the Hall of Fame process, or if you’re gearing up to argue with my picks and want to understand my philosophy in order to have a constructive debate, I strongly encourage you to read it. But if that’s too much to ask, here is the CliffsNotes version:

I am a relative “Big-Haller” who tends to look for reasons to advocate for borderline candidates rather than find reasons to keep them out, even if that means considering stats I do not value for contemporary player evaluation.

To me, Cooperstown is about honoring the game’s greatest more than the game’s best — when comparing two players, the one I consider more special isn’t necessarily the same as the one I would have preferred to be on my team.

I make no distinctions between candidates who are generally deserving and those who are worthy of first-ballot or unanimous selection, though I am willing to prioritize players whom I expect to finish close to 5% or 75%.

Cheating allegations against a player (which, with one notable exception on this year’s ballot, mean performance-enhancing drugs) typically do not deter me from voting for him, but may influence my thinking depending on how strong the evidence is, how much of an competitive advantage they realistically gained, and how the sport viewed such behavior contemporaneously.

Given how immortalization in Cooperstown blurs the distinction between celebrating the accomplishments and venerating the man, inducting a player who is known to be an odious person is not worth the pain that it would bring to his victims (or those who have been harmed in similar circumstances).

We can agree to disagree about each of these principles. If you think Cooperstown should be reserved for only the game’s true best players, that’s your own aesthetic preference (though you have to explain Rabbit Maranville). If you’re unwilling to recognize any player who used PEDs, I’d say your perspective is ahistorical, but that’s your prerogative. If you believe on-field performance is all that should matter for whom to invite to the podium on Induction Weekend, I’m not interested in arguing with you about it — not because I’m sure that my perspective is correct (more on that in a moment), just because such a debate would likely be neither fun or constructive. You may have different evaluation criteria, but this is where I’m coming from.

Content warning: Descriptions of bigotry, domestic abuse, and sexual violence; and discussions of offenders’ sports accolades.

There are 14 candidates on this year’s ballot who I believe deserve a spot in Cooperstown based solely on what they did on the field. When I first sat down to write this article, my plan was to write a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure-style voting guide, with one list of the 10 worthiest players from a pure-baseball perspective, and another that considered whether the people themselves are deserving of celebration. But I quickly realized that such moral judgments resist clear binary classifications. After filtering out the obvious bad apples, there remained men on the ballot whose values I do not share and whom I would not want to befriend, but whose scandals may not rise to the level of denying them baseball’s highest honor. I think reasonable people can disagree, and have their thinkings evolve, about where to set those boundaries.

So here’s what I’ll offer you instead: Below you will find my list of the 14 players I would support if I knew nothing about them off the field, roughly in order of how worthy they are based on their career accomplishments. I will also lay out what gives me pause about them as people, where applicable. You can consider the first 10 players to be my pre-character-clause endorsees, and substitute as many of the next four as you need (and who don’t have their own such baggage) for the better candidates whom you would feel uncomfortable supporting. To be clear, there are multiple players discussed below whose personal conduct I believe should be disqualifying for Cooperstown, but I’m going to let you draw that line for yourself.

1. Alex Rodriguez

Many remember Rodriguez as one of the greatest heels in recent baseball history. He earned his reputation for signing what was then the largest-ever contract in MLB history in 2000, then breaking his own record in 2007. For emblematizing the early-aughts financial dominance of the New York Yankees. For his high-profile feud with teammate Derek Jeter. And for slapping the ball out of Boston Red Sox pitcher Bronson Arroyo’s glove in a tense playoff game.

Yet whatever you think of his playing persona, A-Rod was one of the greatest players of all time. Whether you call him a shortstop or a third baseman, he has a strong claim as the best player ever at his position. If his 696 home runs and 3,115 hits aren’t convincing enough, he won three Most Valuable Player awards and deserved at least a couple more. He ranks among MLB’s top eight hitters in career homers, runs scored, RBI, and total bases, and he climbed the offensive leaderboards while winning multiple Gold Gloves at the second-hardest position on the field.

A-Rod’s first appearance on the ballot last year should have been one of the easiest yeses in the history of Cooperstown voting. Alas, only 34% of the BBWAA marked him on their ballots, less than half the support he needed for induction. This is in part due to many writers simply not liking him — silly as it sounds, such things can indeed affect how they vote — but it is mostly because of Rodriguez’ use of PEDs. And unlike many of the other poster boys of the Steroid Era, there’s no ambiguity about whether he broke MLB rules: Following a prolonged media and legal circus that cemented his reputation as the sport’s main villain, Rodriguez was found to have used human growth hormone in violation of the league’s ban on it and was suspended for the entire 2014 season. He is also widely accepted to have tested positive for a banned substance in 2003, though that was in the context of a non-punitive league survey whose results were supposed to remain anonymous, and whose results were leaked years later by nameless sources. Still, I fervently believe that he would have been a slam-dunk Hall-of-Famer even without illicit enhancements. God only knows how many players have injected themselves with foreign substances since Pud Galvin experimented with testicle elixirs more than a century ago. Most of them didn’t turn out like A-Rod.

2. Manny Ramirez

Stop me if you’ve heard this one: A player who was one of the greatest hitters and biggest personalities of his generation, and who once held the distinction of signing the second-largest contract in MLB history, has had what should have been a suspense-free Cooperstown coronation torpedoed by getting suspended for PEDs late in his career. Ramirez’ Hall of Fame case is admittedly weaker than Rodriguez’ (he has topped out at 29% in six years on the ballot) for two reasons. The first is that he was a repeat juicing offender, earning suspensions for banned substances in both 2009 and 2011 (as well as allegedly testing positive in the non-punitive 2003 survey). The second is that he provided no value to his teams outside his bat. FanGraphs’ Defense metric, a component of Wins Above Replacement that estimates how much a player helped with his glove in terms of both defensive ability and positional difficulty, is admittedly a crude measurement for historical players. But it’s nonetheless telling that, at 277 runs below average, Ramirez ranks as the second-least-valuable fielder of all time.

Yet for all his positive tests, defensive limitations, and personal goofiness, Ramirez was simply one of the great hitters ever. He finished his career with 555 home runs, which is particularly impressive since he never hit more than 45 in a season. He’s one of only seven players in MLB history to hit more than 25 homers 12 years in a row, and one of just 11 to bash at least 20 in 14 straight seasons; it probably goes without saying that all his peers on each list either are in Cooperstown or would be if not for their scandals. And that doesn’t count the playoffs, where his 29 taters represent the all-time record. The complete list of right-handed hitters to have a career OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage) at least as high as Ramirez’ in as many or more plate appearances is…well, just him. Include lefties and you get three more comps: Barry Bonds, Babe Ruth, and Ted Williams. That’s Manny being Manny.

3. Billy Wagner

There’s an interesting debate to be had about how to evaluate relief pitchers’ places in history. Relievers’ jobs, by and large, are easier than starters’. Even modern pitching analysis, with its fuzzier definitions of roles and appreciation for putting your best arms in the most-important situations, is predicated on the notion that it’s easier to throw one inning at a time than six or seven. Consider Huston Street and Andy Pettitte, both of whom are on the ballot this year. Including the playoffs, Pettitte pitched over five times as many innings as Street in their respective careers. How do you even compare Street’s accomplishments to Pettitte’s? Hall of Fame worthiness is about more than quantity, and anyone who’s played the sport at a high level will you that being on the mound in the ninth inning is much harder than taking the ball in the second, but it makes sense that Hall of Fame standard for relievers should be extremely high.

That doesn’t matter for Billy Wagner, because wherever you set the bar, he is far above it. Over the last 100 years of Major League Baseball, 1,094 pitchers have thrown at least as many innings as the 903 Wagner accrued in his career. Here is the complete list of such players whose ERAs are better than Wagner’s 2.31:

Mariano Rivera

…and that’s it. But the fact that there’s even one name ahead of him is fairly notable. By contrast, Wagner’s 33.2% strikeout rate isn’t just the best in MLB history. It’s over two points ahead of second place (Jacob deGrom at 30.8%). The feat is all the more impressive considering how strikeouts have increased over time — the league average K% was six points higher in 2022 than it was when he debuted in 1995. Wagner’s .184 batting average against also represents the Major League record, and the margin between him and the runner-up (Nolan Ryan’s .200) is the same as between second and 19th. And he did it with his left arm despite being a natural right-hander! Wagner has a credible claim as the most-dominant pitcher in baseball history, and it’s preposterous that he has lasted eight years on the ballot without being granted entrance to Cooperstown.

4. Andruw Jones

A few paragraphs up, I mentioned FanGraphs’ Defense metric, a holistic measurement of a player’s defensive value based on how hard of a position he played, how much time he spent there, and how well he played it. By no means should this be the foundation of a Hall of Fame case — defensive ratings are noisy enough when they’re derived from modern tracking data, let alone when they’re based on decades-old box scores — but broadly speaking the career leaderboards look sensible. It passes the sniff test that Willie Mays ranks as the second-best defensive outfielder of all time. On Baseball-Reference’s Total Zone leaderboard, the runner-up is Roberto Clemente, which makes sense in a system that puts center fielders on the same scale as corner outfielders.

The top-rated outfielder on both lists is Andruw Jones, but just saying that he ranks first doesn’t do his numbers justice. FanGraphs sees Jones’ glove as worth 109 runs more than Mays’ over the course of their careers, a gap larger than the margin between the #2 Mays and the #32 Chet Lemon. He also has a 48-run edge over Clemente.

This — along his with his 10 Gold Gloves, countless web gems, and rave reviews from anyone who watched him roam the outfield in his prime — is a long way of saying that Jones has a credible claim as the best defensive center fielder in baseball history. This alone makes him a Hall of Famer in my book, since I believe being an all-time great at a single aspect of the game is sufficient for enshrinement. But while he wasn’t a generational talent as a hitter (there are three players on the ballot whose career OPSes are better than the .922 Jones posted in his best offensive season), he was a pretty good one. His 434 career home runs rank 48th in MLB history, and he’s one of only 26 players to hit more than 50 in a season. His agility in the field also translated to the basepaths, as he is one of only 22 players to exceed both 20 homers and 20 stolen bases three years in a row.

The biggest detriment to Jones’ candidacy (he has yet to exceed 41% of the vote in five years on the ballot) isn’t the unreliability of historical defensive metrics, or how his good-not-great offensive production compares to the gaudy numbers posted by other outfielders of his era, or how precipitously his performance declined after his 30th birthday — or at least it shouldn’t be. It’s a brutal incident of domestic violence that ought to preclude any fan from seeing Jones the person as a hero.

5. Scott Rolen

At first glance, Scott Rolen may not look like a Hall-of-Famer. He’s a career .281 hitter who batted .300 or better only twice. He had good power, but never hit more than 34 homers in a season. He was terrific at third base and won eight Gold Gloves there, but the hot corner is not considered a premium position, and it’s hard to say he was the best third baseman of his generation when his career mostly overlapped with Adrián Beltré’s. He had just one Top-10 finish in the MVP voting, and otherwise received even downballot support only thrice.1

But the whole is greater than the sum of the parts, and Rolen is the type of player whose career is better appreciated through a modern analytical lens. He walked enough to be well-above-average at getting on base. His overall power production was more impressive than his home run totals would suggest — he had the sixth-most doubles and triples in the Majors over the 16-year span of his career, and four of the five names ahead of him are either in Cooperstown or on this list. Third basemen aren’t held to the same defensive standard as middle infielders, but the runs Rolen saved count just as much as a shortstop’s. He ranks as one of the 10 best overall third basemen ever by both FanGraphs and Baseball-Reference wins above replacement, as well as Jay Jaffe’s JAWS and Adam Darowski’s Hall Rating. The only name ahead of him on any of the WAR-based lists who primarily played at the hot corner and is not already in Cooperstown is Beltré, who ought to be a lock to get in on his first ballot next year. Hopefully Rolen, now seeking induction for the sixth time, will already be there to welcome him.

6. Gary Sheffield

We don’t have good measures of bat speed for players who retired 13 years ago, but anyone who watched Gary Sheffield hit will tell you he swung as hard as anyone who ever played in the big leagues. He used the thunder in his lumber to wreak havoc on opposing pitchers for 22 years, hitting .292/.393/.514 with 509 home runs. As terrifying as he was to face in his prime, his longevity is arguably more exceptional. Sheffield is one of only three players in MLB history to put up a wRC+ (FanGraphs’ park- and league-adjusted holistic hitting measurement) above 135 in at least 250 plate appearances 12 years in a row, along with Barry Bonds and Manny Ramirez. Change the criteria to 14 consecutive seasons with a wRC+ of at least 122 and the only additions to the group are Alex Rodriguez and Rickey Henderson.

Sheffield’s only major on-field weakness was defense, though it was a big one — speaking of ways Sheffield compares to Ramirez, he is the only player in MLB history whom FanGraphs rates as a less-valuable defender than Manny. (This is the last time we’ll talk about those numbers.) But the bigger reason why he’s on his ninth try to get into Cooperstown is his connection to PEDs. Sheffield has admitted to unknowingly using a steroid cream in 2002, though he has been accused of doping more extensively and intentionally than that. Other troubling controversies include being charged with assault while in the minor leagues, getting into a fight with a fan during a game, and for making offensive comments about Latino players while discussing systemic racism within the sport.

7. Todd Helton

Todd Helton did a lot of things really well. He hit for average, including batting .372 in 2000 — one of only five players in my lifetime to hit above .370 in a full season, and the most-recent to do so in the National League. He walked more than he struck out. He could hit for power, including leading the sport with 592 doubles over the years of his career and placing third with 998 extra-base hits. He slugged over .600 four times, including the highest peak (.698) of anyone on this year’s ballot. He was widely regarded as a strong defender, and won three Gold Gloves.

So why is Helton still waiting after four times on the ballot? The simplest way to put it is that he is a victim of expectations. The offensive bar for Hall of Fame first basemen is sky-high, both because they contribute little defensive value at the easiest position on the diamond, and because of how many of the game’s great luminaries also played there. Then, if you account for the cartoonish power numbers Helton’s peers put up in the height of the Steroid Era and the thin, ball-flight-enhancing air of Colorado (where he spent his entire career), his 369 home runs look underwhelming by Cooperstown standards. But while adjusting for these contexts is both fair and important, I think the narrative surrounding Helton has overcorrected. In recent years, the baseball community has come to understand that playing half of one’s games at Coors Field distorts hitters’ instincts for how pitches move. In other words, the fact that Helton homered in 5% of his plate appearances in Colorado but just 3% elsewhere is partly because it’s easier to hit in Denver, but the disparity is amplified by the Coors hangover Rockies players experience on the road. I also have a longstanding hunch that the predominant linear-scaling method for park adjustments doesn’t give enough credit to standout performances in unique environments.2 He's far from the most glaring omission from the Plaque Gallery, but he more than earned a place in it.

8. Carlos Beltrán

Center fielders are in a tough position (pun intended) when it comes to the Hall of Fame. They fall into a sort of doughnut hole where they are judged alongside corner outfielders offensively, compared to other up-the-middle players defensively, and evaluated in the shadow of a high concentration of inner-circle all-time greats — you can make plausible list of the Top 5 center fielders ever that doesn’t have Ken Griffey Jr. on it. This dynamic is why recent deserving candidates like Kenny Lofton and Jim Edmonds failed to reach even the meager 5% required to stay on the ballot. With that in mind, there isn’t a single specific statistic that demonstrates why Carlos Beltrán is worthy. He was just really good. He had impressive power, belting 435 home runs across 20 seasons. (In the context of the other players we’re discussing, it’s easy to forget that 435 is a lot of dingers.) He had great speed, swiping 312 bases with a high success rate (86%). Only four players in MLB history had both more homers and more steals, and only three had more 20/20 seasons than Beltrán’s seven. He won three straight Gold Gloves from 2006-08. He is also one of the best playoff hitters of all time, as his 1.021 career OPS leads all players with at least 200 PA in the postseason.

Like many players on the ballot, Beltrán has been credibly accused of cheating. But not with performance-enhancing drugs. Beltrán was named as the ringleader and co-creator of the Houston Astros’ sign-stealing scheme, in which they illegally used technology (and a trash can) to alert their hitters to what kind of pitch they were about to see. Stealing signs without the use of technology (i.e., a runner on second base relaying what he sees from the catcher to the hitter) is an accepted part of the game, Beltrán has claimed that the Astros were not alone in deploying such tactics, and we don’t know how much hearing the bangs from the dugout actually drummed up his numbers. But there is a real difference between the juicers engaging in long-established behavior that the league had previously condoned and Beltrán innovating and evangelizing new methods of unambiguous cheating. I would probably vote for him regardless, but I respect those who draw the line here.

9. Omar Vizquel

Until a couple years ago, I would have been eager to lay out the contrarian case for my onetime favorite player. From a pure baseball standpoint, I believe that being one of the most-lauded defensive players of all time and (to a lesser extent) his great contact skill in an age when league strikeout rates were ticking up make Omar Vizquel worthy of Cooperstown. Yet I can’t make this argument with any enthusiasm because in addition to being the worst overall player on this list — his OPS+ is barely half of Manny Ramirez’ — he is the worst person. Vizquel is accused of committing both domestic abuse at home and sexual harassment and ableist bullying in the clubhouse over long periods of time and as recently as three years ago. His glove deserves a place in the Plaque Gallery, but it’s not worth inviting someone that odious to the podium for Induction Weekend.

10. Bobby Abreu

The ten-vote maximum for Cooperstown ballots is an arbitrary limit, but it makes this spot feel pivotal. To be honest, in my first few versions of this list, Bobby Abreu was not ranked this highly; when I first sat down to do my homework on the 2023-eligible class, I wasn’t sure that he would even make the cut as an honorable mention. But the more I looked at Abreu, the more I’m convinced that he is worthy of immortality.

Abreu was not widely considered an elite player in his own time. He never finished higher than 12th in an MVP vote. This is partly because one of Abreu’s best skills was how often he walked, and in his heyday the sport was only just coming around to appreciating how valuable that is. It’s also because Abreu was more remarkable for his consistency than his peak performance. Consider the following list of every player in MLB history who had 14 straight seasons with at least 575 PA and a walk rate of 10% or better:

Bobby Abreu

That’s the whole list. But okay, even if you understand the importance of plate discipline, you don’t walk your way into Cooperstown. Luckily, Abreu could also run. He stole exactly 400 bases, and is one of only 12 players to have a streak of 14 consecutive seasons with at least 19 steals. And while he was never known as a premium slugger (he exceeded 20 homers only four times and maxed out at 31), he led the Majors with his 633 doubles and triples over the span of his career. Only four other players stole at least as many bases and hit as many home runs as Abreu did over his 18 years in the big leagues.

Anyway, back to Abreu’s consistency. Here is a complete list of players who had a 12-year run of consecutive .810 OPSes or higher in 575 or more PA:

Hank Aaron

Lou Gehrig

Willie Mays

Stan Musial

Albert Pujols

Paul Waner

Bobby Abreu

Abreu actually has company this time, and it’s six guys who either are or will be in the Hall. (Paul Waner is a pretty impressive worst-case comparison.) Speaking of impressive feats of consistency, here is every MLB player in history with 10 straight seasons of 15 homers and 15 steals:

Barry Bonds

Bobby Abreu

How about hitters who went 15/15 eleven years in a row?

Barry Bonds

Bobby Abreu

Twelve years:

Barry Bonds

Bobby Abreu

Thirteen years:

Barry Bonds

Bobby Abreu

Yes, I cherry-picked the 10-year threshold as the starting point above because that’s where the list gets whittled down to two names. So in the spirit of intellectual honesty, here are all the players who strung together nine straight 15/15 seasons:

Henry Aaron

Barry Bonds

Bobby Abreu

This is Abreu’s fourth year on the ballot. So far he has topped out at 9%. I hope his tendency to go on decade-long streaks does not extend to losing the BBWAA vote.

For those keeping score at home, we have now exhausted our 10 allotted picks under the BBWAA’s voting rules. Yet since there are at least a couple players above whose personal behavior ought to preclude their being celebrated in Cooperstown, here are the four other candidates on this year’s ballot whom I believe are worthy of induction (at least from an on-field perspective).

11. Mark Buehrle and 12. Andy Pettitte

Mark Buehrle and Andy Pettitte are remarkably similar players. Both are left-handed starters whose Cooperstown cases are based more on sustained quality than concentrated dominance. Their career totals are separated by just 33 innings pitched and four points of ERA. They are just three spots away from each other among the Hall of Stats’ ratings for historical pitchers, and are only two ranks apart on the list of starters by JAWS. And they hold similarly tenuous places on the Hall of Fame ballot: Pettitte got 11% of the vote on his fourth try last year, while Buehrle received just 6% support in his second attempt in 2022.

The challenge Buerhle and Pettitte face is how pitcher evaluation has changed over the last couple decades. They came up in an era of relatively high offense, and while they were relative innings-eaters by modern standards, their workloads are unremarkable in the grand scheme of baseball history. The upshot is that if either were inducted, he would both have the second-worst ERA of any Hall of Famer and fall a couple hundred innings shy of the Cooperstown average. That’s why controlling for the context is so important. By ERA+, Baseball-Reference’s metric that scales a pitcher’s ERA to the run environment he pitched in, both Buehrle and Pettitte come in at 117, meaning they were 17% better at preventing runs than an average pitcher on a per-inning basis. That puts them just behind recent inductees Bert Blyleven (118) and Tom Glavine (118), and ahead of legends like Steve Carlton (115) and Nolan Ryan (112).3

In the initial version of this list, I had Pettitte above Buehrle (and both over Abreu) because of his postseason success. Pettitte pitched more than a full season’s worth of high-quality innings in the playoffs, racking up 19 wins and 276.1 IP (both MLB records) along with a 3.81 ERA en route to five World Series championships. What changed my mind (and inspired me to discuss them together) was considering how they gained the respective competitive advantages for which they are famous. Pettitte has admitted to using human growth hormone, though he sanctimoniously insisted that he did so only to rehabilitate an injury, which he believes is less wrong than juicing to improve on the field. By contrast, Buehrle consistently outperformed both his stuff and his expected results thanks largely to his own defensive skill. Defensive Runs Saved estimates that the four-time Gold Glove winner prevented 87 runs as a fielder, tied with Zack Greinke for the most for a pitcher since tracking began in 2002 (no one else has more than 63). I don’t consider Pettitte’s HGH usage to be disqualifying, but between two players who found distinctive ways to get a leg up, I prefer the one who made his own luck.

13. Jeff Kent

This is Jeff Kent’s 10th and final year on the ballot, so there isn’t much to say about his candidacy that hasn’t already been rehashed. Kent was a good and occasionally great hitter and was generally considered a solid but not superlative middle infielder. He is a borderline candidate whose induction would not lower the standards of Cooperstown but whose omission would not be egregious. Your opinion on Kent probably depends on how big you think the Hall of Fame should be. I would put him in, but as you can probably infer, I do not feel particularly passionately about his case. Given that this is his last year on the ballot and he has consistently received less than a third of the vote, it’s probably a moot point anyway. Kent has courted controversy off the field, including some conspicuous feuds with Black teammates and making a $15,000 donation to support a proposition banning same-sex marriage in 2008.

14. Francisco Rodriguez

As with Omar Vizquel, there isn’t much support for Francisco Rodriguez among the baseball analytics community, and I would be far more enthusiastic about making this contrarian argument if not for his personal baggage — in this case, a lengthy history of domestic violence. In short, I think Rodriguez the player is worthy of recognition because he helped cement the role of the modern closer. Had he hung up his cleats after the 2016 offseason instead of holding on for one more year, he would have finished with what was then the highest strikeout rate (28.7%) among pitchers with at least as many innings in MLB history, along with the sixth-lowest ERA (2.73) in the preceding century. Alas, he still holds the record for most saves in a season (62 in 2008), and his nickname is one of the coolest ever in the sports: K-Rod. He ranks in a tier below the likes of Mariano Rivera and Billy Wagner, and his personal conduct should disqualify him regardless, but I think his numbers put him over the bar of requisite dominance for Cooperstown.

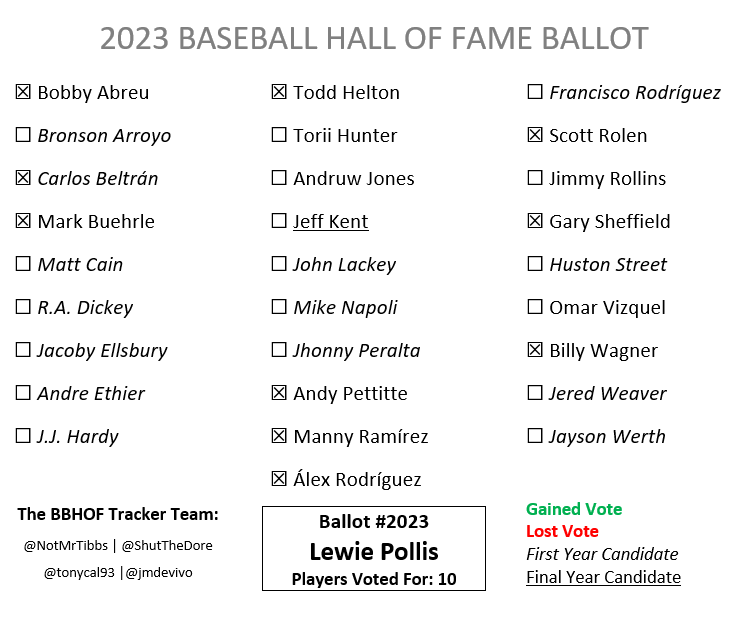

About 5,000 words ago, I wrote that there isn’t a good answer for where to draw the moral line on this year’s Hall of Fame ballot. If you can sleep at night having voted for Jones, Vizquel, or Rodriguez, I don’t begrudge you that. If there’s someone else you think is too dishonorable to invite to the podium, I respect that too. But after weighing performance and personality, metrics and morals, here’s how I’m filling out my imaginary ballot (with an official BBHOF Tracker image from Ryan Thibodaux!):

Huge thank yous to FanGraphs and Baseball-Reference/Stathead for hosting the statistics cited in this post!

Rolen’s spectacular 2004 campaign deserved more acclaim than fourth place, but it came in a year when 10 National Leaguers posted seven-win seasons, depending on your preferred flavor of WAR.

As an extreme example, consider two players in dramatically different run environments: One who hits .275 in a league where the average is .200, and one bats .400 when the baseline is .300. The former has a proportionally higher batting average — 38% vs. 33%, or a 138 AVG+ compared to 133 — but I suspect the latter was a tougher accomplishment.

It hopefully goes without saying that Carlton and Ryan had other strengths, including the fact that they each pitched about 2,000 more innings than Buehrle and Pettitte.

Shh... Don't let folks know I learned it here but you did just help me sound more in-the-know at the dining room table.