The Shift is Hitting the Ban

How baseball's new rules are inadvertently increasing strikeouts

There are many reasons why strikeouts are more common than they used to be. Pitchers at all levels are throwing harder every year, going at max-effort for shorter stints instead of pacing themselves to last deeper into games. Coaches are helping players develop better pitches based on what increasingly intricate data shows is most effective, then encouraging them to use their best offerings more often. Meanwhile, the modern game’s emphasis on power — the dreaded “launch-angle swing,” you’ll hear old-timers grumble, as though geometry had been discovered only in the last few years — means hitters are willing to sacrifice quantity of contact for quality of contact.

At the risk of oversimplifying decades of baseball evolution, I think the myriad explanations boil down to one thing: A divergence in incentives. For pitchers, high strikeout rates are virtually always good. For hitters, strike three is embarrassing, but in terms of on-field value, it’s typically not that much worse than making another kind of out. Batters who strike out a lot also tend to hit for more power, and especially since sabermetrics started influencing team decision-making, that’s a tradeoff teams are happy to make (at least to a point). Thus, pitchers have more incentive to pull strikeout rates up than hitters do to push them down, and the league equilibrium has shifted accordingly. Here’s a look at how that has manifested over the last 70 years of baseball history (since box-score stats began being tracked with near-modern detail). You can see where the analytical revolution started spreading in earnest.

The increase in strikeouts is part of a broader decline in in-game action that MLB sought to reverse with a slate of new rules for the 2023 season. I’m a fan of the bigger bases, a win for player safety that have also helped drive a 40% increase in stolen bases per game compared to last year. I still don’t like the concept of a pitch clock in a sport that famously operated on its own dimension of time, and after experiencing a game where it took only an hour to play five and a half innings I think the league has overcorrected, but I will begrudgingly admit that something had to be done about the increasingly lackadaisical pace of play. It’s certainly keeping fans more interested.

And then there are the new rules about defensive positioning, commonly referred to as the shift ban. This was pitched as a way to improve the on-field product on two fronts. Limiting a fielder’s ability to stand where the ball is most likely to go obviously means it’s more likely to fall for a hit, thus injecting more offense into the game. In addition, as balls in play are more likely to find holes, hitters have more incentive to just make contact — if a rolled-over grounder isn’t an automatic out, then it’s no longer functionally equivalent to a strikeout. Something would finally stem the game’s spiking strikeout rates.

My vehement opposition to the shift ban is well-documented. Even if it worked at increasing batting average on balls in play (BABIP) — which I didn’t think it would; I’ve already admitted to being wrong on that — the overshift had been a legitimate baseball strategy for a century, while policing offsides has never been part of the sport. The shift was scapegoated as the embodiment of what’s wrong with modern baseball, vilified only for its (overblown perception of) effectiveness. There were no issues of cheating or player safety. It’s a matter of degree, not principle, that separates banning the shift from outlawing triple-digit-velocity fastballs.

The Athletic’s Eno Sarris noted this week that, in spite of the rule changes, strikeouts haven’t just failed to fall — they’ve gone up. The jump in leaguewide K% from 22.4% in 2022 to 22.8% so far this year isn’t enormous, but it’s not negligible (on the order of one every four games) and it’s not the direction MLB was hoping to see. Sarris ultimately concludes from his reporting (which is well worth a read) that the heart of the problem is the league’s ever-increasing velocity, which the new rules can’t fully mitigate. Yet I would argue that the changes aren’t just insufficient for reversing the sport’s years-long strikeout trend. The shift ban is hastening it.

To start, any discussion of the theoretical strikeout-reducing effects of restricting defensive position must account for pitchers having agency, too. Every bit of incentive hitters have to make more contact has an equal, opposite implication for pitchers’ incentives to allow less contact. And as recent history has demonstrated, pitchers around the league are more than capable of doing their part to move towards a rational equilibrium. But that merely explains why the league’s strikeout rate isn’t dropping, not why it’s rising.

If I asked you to imagine a player who was particularly vulnerable to the shift, what would you picture? Probably a hulking left-handed slugger. Below-average speed. Someone who swings for the fences, not to hit it where they ain’t. When a batted ball of his falls prey to the shift, it’s the result of getting jammed or hitting it off the end of the bat. These are generalizations, but they’re not baseless — there’s a reason why teams didn’t shift against Myles Straw.1

Hitters who check these boxes also tend to have something else in common: They strike out a lot.

It turns out this connection is more than anecdotal. The following chart shows the relationship between strikeout rate and shifted-against rate for left-handed hitters last year. The correlation is hardly perfect, but apparent. A 5% increase in a batter’s strikeout rate translates to a 6% increase in how often he’s shifted.2

Right-handed hitters aren’t shifted as often as lefties, so it’s not surprising that the relationship with shift rate is weaker. But it’s visible nonetheless:

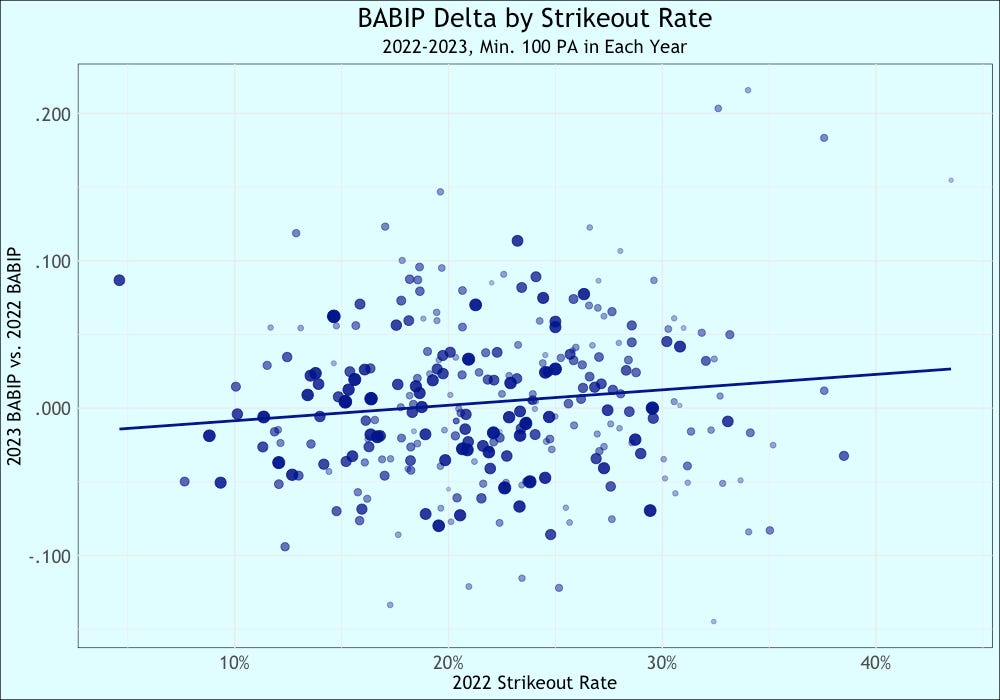

It follows that hitters who had high strikeout rates last year would see bigger BABIP improvements under the new rules this year. Indeed:

To be fair, we’re not doing much in terms of explanatory power (the trendline above has an R2 of just 2%). But the relationship is linearly significant, with the delta between the least- and most-strikeout-prone players in baseball translating to a difference-in-differences of over 40 points of boosted BABIP post-shift ban. Survivorship bias could be a factor in these numbers (if a player with a high strikeout rate last year is still getting significant playing time this year, he’s disproportionately likely to have made some offseason improvements), but there’s no correlation between the BABIP and K% deltas. Further, what we see this year bucks the recent historical trend: the relationship between strikeout rate and BABIP improvement without an intervening rule change is typically either nonexistent or negative:

Which leads us to the inadvertent side effect of the shift ban: As low-contact players become more comparatively valuable, teams are incentived to give high-strikeout hitters more playing time. Since 1954, the median season has seen 43.3% of plate appearances taken by hitters with average-or-worse strikeout rates.3 This year, that’s up to a record-high 48.4%. The 2023 season also ranks in the top three for the largest proportion of PA given to hitters with strikeout rates at least 5% higher than the respective yearly norm (21.4%, up from 19.9% in 2022). We are lagging only the strange shortened 2020 season with 35.9% of PA taken by hitters with strikeout rates of 25% or higher (2022: 32.6%) and 14.8% allocated to batters with 30%+ K%s (2022: 12.4%).

Of course, these measurements are directly related to the overall strikeout rate and have been ticking up over time, so this year’s spikes could just be continuations of the existing trends. But note that each of the above lines dips after 2020 before cresting again this year. The proportions of at-bats given to players with (what were once considered) extreme strikeout rates were lower in both 2019 and 2021 than they are now even though the league K% is down.4

So there you have it: In an ironic twist, a rule meant to encourage putting the ball in play is instead fueling the sport’s arms race of strikeouts by incentivizing teams to select for lower-contact hitters.

This is not the strongest statistical argument I’ve ever made.

Observing that all-or-nothing hitters tend to be good shift candidates is not groundbreaking baseball analysis. The relationship between strikeout rate and BABIP improvement is tenuous enough to illustrate the difference between statistical and practical significance. What I call an acceleration of teams abiding once-intolerable strikeout rates could be a blip in a noisy trend. I sincerely believe there’s something here, but it’s only fair to recognize my anti-anti-shift bias, and my pet peeve of people invoking game-theory terminology to defend the new positioning rules without acknowledging the competing incentives to keep strikeout rates high.

Yet the logic is compelling. A certain hitting style becomes more valuable under the new rules. Teams increasingly seek out these batters, so they get more playing time. Their shared characteristics impact the league ecosystem — but subtly.5 If the theory were true, these small-magnitude trends are exactly what we would expect to see.

Dare I say this perverse incentive was predictable? As I wrote in March:

Yet the (not always accurate, but not baseless) stereotype of the players who are most vulnerable to defensive positioning — the ones who will benefit most from the new rules, and thus whom teams will increasingly seek out under the new rules — is that they are plodding, all-or-nothing hitters who walk and strike out a lot. … The new rule dovetails with this trend, and I wouldn’t be surprised if it ultimately leads to fewer balls hit into play.

For years, the main counterargument against proposed attempts to curtail the quirks of modern baseball was that they were solutions in search of problems. Fluctuations in who has the advantage between offense and defense are cyclical. If the shift were a novel tactical development that dramatically tipped the balance of the sport as opposed to a long-established strategy that happened to become the symbol of what’s wrong with today’s game, hitters would have adjusted their approaches without waiting for the league to intervene. Whatever you think of professional sports’ ruthless drive towards analytical efficiency, modern teams are really good at understanding the incentives the game provides them with. Would that the curmudgeons who hate strikeouts so much that they accidentally caused them to go up could say the same.

Straw was shifted exactly once his rookie year, and responded by hitting a homer. Per Baseball Savant, he hasn’t seen a shift since. It also took him three years to hit his next big-league homer. Baseball!

Shift rate is based only on pitches with the bases empty. Switch-hitters are included here with their full-season strikeout rates and handedness-specific shift rates. Circle size and opacity are proportionate to plate appearances. All chart data as of June 8 and courtesy of Bill Petti and Saiem Gilani’s terrific baseballr package.

If the fact that this isn’t 50% seems like a paradox, consider the impact that pitchers hitting used to have. Most pitchers didn’t get many at-bats, but collectively they batted enough to impact a given year’s run environment.

Implementing the universal DH in 2022 provided a superficial break in the established trend. Excluding pitchers hitting, 2023’s K% ranks behind only 2020’s.

The domino effect from the league’s current seven-point BABIP increase over last year (roughly an extra seeing-eye single every three games) wouldn’t radically upend how front offices evaluate players.

This is really good and though-provoking. I agree that teams have additional incentive to play low-contact hitters, but I would also point out that the player development environment of the last decade plus has created more of those players than it has Myles Straws and Steven Kwans and thus they are more readily available. Where we differ in opinion is that it seems reasonable - to me - that the shift rules require more athletic fielders who are likely to profile differently at the plate as well. That change will take more time to appear, and if K-rates continue to rise they will obviate any incremental athletic benefit.