Let Out the Vote

Time to end the Baseball Hall of Fame's secret ballots

On July 23, Fred McGriff and Scott Rolen will take the stage in Cooperstown and be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

For McGriff, his selection last month was a long time coming. Aside from candidates who got mired in controversies about performance-enhancing drugs, no other heretofore-eligible player with at least as many home runs as the 493 McGriff hit over 19 years in Major League Baseball has been kept out of Cooperstown. If not for the strike that claimed much of the 1994 and 1995 seasons (he had 34 homers when the 1994 season ended two months early, and hit 27 after the delayed start in 1995), he would almost certainly have reached the magic number of 500. However, he languished well below the 75% requisite threshold for induction on each of Baseball Writers Association of America’s Hall of Fame ballots from 2010-19. The Eras Committee — a special group tasked with reconsidering historical players who were passed over in the typical electoral process — belatedly righted that wrong in December.

On Tuesday night, Rolen got the call for induction as well. It’s a remarkable climb for the third baseman, who got 76.3% of the vote in his sixth try on the ballot. As mentioned on MLB Network’s coverage of the announcement, the BBWAA had never before elected a player who initially got as little support as the 10.2% he received on his first try in 2018. Why he received so few votes initially is beyond me. Kudos to the writers for belatedly recognizing his accomplishments.

Rolen’s election is a terrific moment for baseball, and his enshrinement will be rightfully celebrated in the coming months. Still, it’s hard not to notice that, by my count, there were 14 players on this year’s BBWAA ballot whose on-field contributions were worthy of enshrinement. (This number is smaller if, like me, you prefer not to celebrate players who committed acts of sexual assault or domestic violence, but recent history shows that most voters are willing to overlook such things.) Which means that a lot of deserving players have been left out in the cold — like longtime Colorado Rockies first baseman Todd Helton, who fell an agonizing 11 votes shy of immortality.

Arguably the main sources of this disconnect are the controversies surrounding performance-enhancing drugs. By any reasonable standard, Alex Rodriguez is one of the best players in baseball history, and Manny Ramirez ought to be considered among the greatest hitters of all time. Yet neither received even half of the 75% support needed for induction in this year’s balloting, as modern voters apply anachronistically harsher judgments towards PED users than what the consensus attitudes were in even the not-that-long-ago era in which they played.

Players also have to contend with the fact that — to be blunt — many voters do not take candidates seriously until after they’ve spent a few years on the ballot. Some players do get in on their first try, but that honor has recently been bestowed only on those whose on-field accolades have been supported by overwhelming popular narratives. Of the four candidates in the last five years to have been inducted on their first ballots, three — the New York Yankees’ Derek Jeter and Mariano Rivera and the Boston Red Sox’ David Ortiz — were the main characters in the greatest rivalry in American sports at the peak of its intensity. The other, Roy Halladay, was elected posthumously, having tragically passed away before he was eligible for induction.

Rolen himself is a terrific example of this phenomenon. In another context it might sound strange, and perhaps even embarrassing, that nearly two-thirds of the veteran sportswriters of the BBWAA changed their minds about his Cooperstown worthiness between his getting 10.2% of the vote in 2018 and his 76.3% showing this year. Or consider the would-be Hall of Fame class of 2013, when the BBWAA snubbed the entire slate. Ten years later, a whopping 10 players from that ballot have been selected into Cooperstown — a figure that does not include the three best ones, who may still get there one day as (for better or worse) the saliences of their respective controversies fade from the zeitgeist. Nothing about the belated inductees’ résumés changed between that election and their eventual enshrinements, as each had already been retired for at least five and in one case as many as 18 years. For some reason, baseball has normalized the notion that the esteemed vanguards of the game needn’t do their due diligence for bestowing the game’s highest honor until after a player has gone through a few rounds of a process so stressful that it is actuarially measurable.

Yet there’s another looming factor that may have played a role in keeping at least one player out of Cooperstown this year: Anonymity.

The secret ballot is a foundational tenet of popular democracy. Your rights as an American citizen are not contingent upon whom you vote for (except insofar as the people you elect may affect them). You cannot be coerced into or punished for casting your ballot a certain way. That’s because, at least in theory, voting is considered a fundamental right.1 You don’t need to be an expert in political science or up on current events. You don’t even have to know what the candidates stand for or care who wins. You just have to be 18 years old and live in a place where those administering the election are not trying to suppress your voting rights.

Yet the right to vote anonymously does not apply in every situation. Consider Congress. Legislators’ names are attached to the votes they cast, and the results of their Yeas and Nays are public record. That’s because participating in a representative legislature is a privilege, not a right. We expect our leaders to be fully informed about the issues they vote upon, to exercise good judgment, and to be able explain their actions to constituents who feel that their values have not been represented. Surely many politicians would rather this were not the case, and that the American public would not notice when their actions conflict with their stated principles, but such transparency is part of the deal. Any legislator who prefers not to go on the record with their policy preferences is free to not seek for reelection, or resign, or to not have run for office in the first place.

The voters of the Baseball Writers Association of America are not elected leaders. Our taxes do not pay their salaries, and they do not derive their authority from the principles of popular sovereignty. However, those who are invited to participate in the Hall of Fame vote — journalists who have worked at accredited publications for at least 10 years and who have been active within the last decade — have some broad-strokes similarities to Senators insofar as their credentialing requirements diminish the utility of secret voting. The BBWAA’s eligibility filters are designed to ensure that the voters know the game of baseball, and have seen or even covered many of the players on the ballot. As professional sports journalists, they should be more than capable of explaining their choices and supporting their arguments for and against each candidate with facts and statistics; many of them subsequently write news stories about the results they helped to create. And most importantly, casting a Hall of Fame ballot is a voluntary privilege, so changing the conditions required to vote is not a violation of anyone’s civil rights.

Despite all that, the BBWAA Hall of Fame allows its voters to submit their ballots anonymously (EDIT2). Many writers upload pictures of their ballots via social media or write columns explaining their choices, which fans hoping to divine the results early have been tracking since at least 2009. Writers can also opt in to have the BBWAA publish their ballots on the official results pages, but they are not released until two weeks after the inductees are announced. But while many Cooperstown voters now publish their choices, a significant number do not — as of this writing, 194 writers out of the 389 participants revealed their picks before the ballot announcement compared to 195 who didn’t, a nearly even split. And when you take even a cursory glance at how the results are split by named and anonymous ballots, a conspicuous pattern emerges.

Not only do those who cast their votes privately vote differently from those who disclose their choices — they vote worse.

The modern king of ballot-tracking is Ryan Thibodaux, whose team started tracking the known 2023 vote totals over a month before Tuesday's results were unveiled. Based on the numbers Thibodaux had compiled prior to the announcement, Rolen, who had 80.7% support among the known ballots, would have expected to be joined in Cooperstown by five-time candidate Todd Helton (78.7%). Billy Wagner (72.5%) and perhaps Andruw Jones (66.7%) and Gary Sheffield (62.8%) also had reason to hope.3 But such projections would have relied on the assumption that those who vote anonymously put as much thought and care into their choices as those who own up to their ballots.

Recent history shows that this is not the case. For five years from 2011 to 2015, I analyzed the splits in the BBWAA voting and found clear patterns relating how good a player was to how his support varied between public and private ballots. To be clear, these correlations do not necessarily imply causation. For example, writers who are well-versed in modern sabermetrics (and thus whose choices generally align more with my ideas of worthiness) are probably more likely to be active on social media and thus more interested in revealing their picks there. There’s a good argument that sharing one’s ballot is probably an indicator of keeping up with contemporary baseball thought, so the causal relationship may work in the opposite direction.

Yet I have long believed that anonymous ballots also give cover for some minority of the BBWAA electorate to vote irresponsibly with no consequence. Consider Pedro Martinez’ candidacy in 2015. Martinez, arguably the best pitcher of my lifetime, cruised into Cooperstown with 91.1% of the vote. But while he garnered near-unanimity (98.0%) from the known named ballots at the time, he got a less-commanding 87.2% from those who voted anonymously. There was no reasonable argument to be made against Martinez, a no-doubt inner-circle Hall of Famer.4 So I don’t think it was mere coincidence that those who cast their ballots in secret were six times as likely to snub him as those who owned up to their choices.

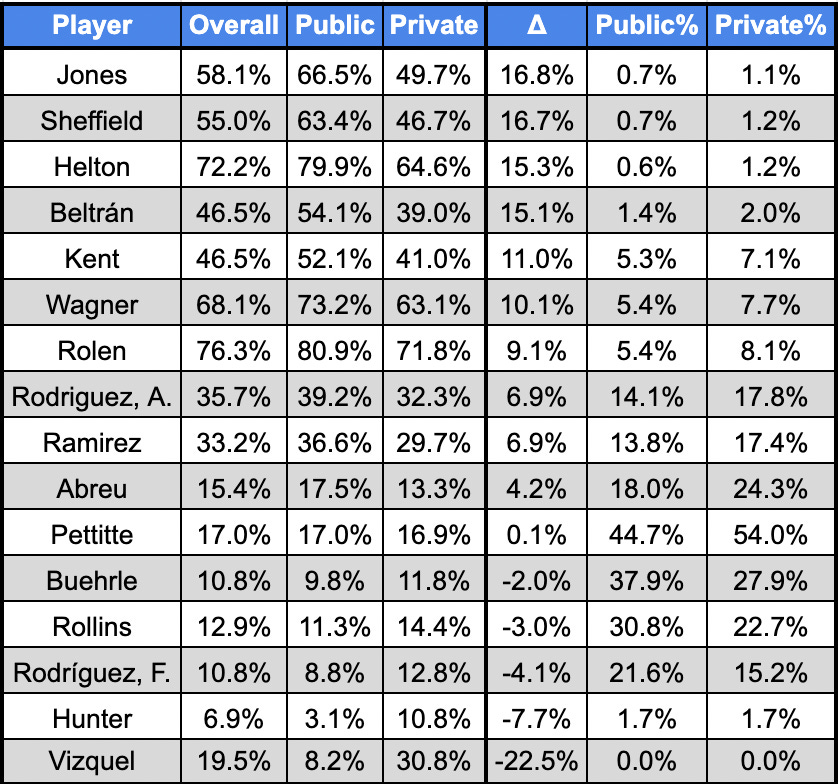

Which brings us to this year’s results. Here’s how the overall numbers (based on Thibadoux’s final pre-reveal count) split out by ballot type:5

Of the 16 candidates who received meaningful support (named on more than one ballot), 11 got more votes from named ballots than anonymous ones. This is to be expected, as public-facing voters averaged 6.2 names per ballot, compared to private voters’ 5.5. It’s also an initial hint about the quality of the votes, if you believe (as I do) that there are at least enough worthy candidates to use up all of one’s allotted 10 selections.

Not all of the deltas here are meaningful. Andy Pettite’s 0.1% drop among anonymous writers represents less than a single vote. The small differences for Mark Buehrle and Jimmy Rollins, and probably the four-percent gaps for Bobby Abreu and Francisco Rodríguez, probably fall within the realm of statistical noise. Even some of the larger disparities are probably better explained by what demographics of writers are more likely to post on social media — it’s not as though denying Manny Ramirez and Alex Rodriguez enshrinement because of their PED suspensions is a fringe position.

But some of the splits are interesting. Below is a more-focused table, ordering the serious candidates by their vote discrepancies and adding a quick estimate of how significant the splits are. The Public% and Private% columns represent the binomial-distribution-based probability of a player diverging from his overall vote share by as much as he did from his named and anonymous voters, respectively, by random chance alone. For example, the odds of Abreu being checked on no more than 26 of the 195 unnamed ballots given his overall level of support are about one in four — not enough to say there’s a true intrinsic difference. (Probabilities are for getting at least as many votes when the split-share is greater than the player’s overall support, and for getting at least as few votes when the subset results are lower.)

The top of this chart may catch your eye. Based on their slight-majority overall support, Andruw Jones and Gary Sheffield would each have had only about a one-percent chance of getting as many votes on named ballots as they did absent any other factors, and as slim odds of dropping as low as they did with anonymous writers. Carlos Beltrán’s discrepancies are similarly unlikely based on a pure random split. On the other hand, Torii Hunter’s support tripling on private ballots relative to public ones probably indicates statistical significance. And there is a particularly jarring gap for Omar Vizquel. Only eight percent of writers who put their names on their votes were willing to own up to supporting the most-odious man on the ballot, compared to almost a third of those who could hide behind anonymity.

And then there’s Todd Helton, whose support plummeted from 79.9% from public voters, well clear of the three-quarters mandate for induction, to just 64.6% on private ballots. There’s no way to know whether any of the unnamed writers who left Helton off their ballots did so in part because they would not have to own up to it. But if that secrecy played a role in at least 11 BBWAA members’ decision not to vote for him — an increase of under six percent support from anonymous voters, representing less than half of the disparity between private and public ballots — then it cost a well-deserving slugger a spot in Cooperstown.

I asserted above that, whatever the cause, Hall of Fame ballots cast anonymously are not just different than those with names on them, but worse. I suppose you could take my word for it that there is a correlation between how good a player was and how much better they fared among public voters than private ones, but we can show this with some quick data-visualizations, too.

Consider the quickly generated chart below. The x-axis represents JAWS, writer Jay Jaffe’s metric for estimating Cooperstown-worthiness. Reducing the nuances of whether a player belongs in the Hall of Fame to a single holistic number is a vast oversimplification, but JAWS has caught on across the industry because its rankings align impressively well with popular perceptions of how players stack up. The y-axis is the difference between a player’s support on named ballots vs. secret ones. While a sample of 16 candidates is admittedly small, the trend is clear: The better the candidate, the bigger the drop-off among anonymous voters.

Another of my favorite attempts to quantity deservingness of immortality is Adam Darowski’s Hall Rating, as hosted on his terrific Hall of Stats site. The interpretation of Hall Rating is simple: a score of 100 equates to being the nth best player in Major League history, where n is the number of players currently enshrined (that count currently stands at 240). Anything at or above 100 means a player is deserving of Cooperstown. The results are pretty similar to the above:

A skeptic might argue that this is confusing cause and effect. A voter who considers modern sabermetric stats like Wins Above Replacement, which fuels both JAWS and Hall Rating, is probably more likely to enjoy discussing their picks on social media. The counterargument is in the graph below, which shows vote-share discrepancies by vote totals. The better the candidate, according to the BBWAA electorate themselves, the more his support decreased among writers who didn’t reveal their choices.6

Perhaps everything that could be written on this subject has already been said. A child who was in first grade when I first started this series of anti-secrecy screeds would be a freshman in college by now. (To be fair, I did take an eight-year hiatus.) Even if supporting mandatory vote reveals was once a hot take, it’s at best a lukewarm one now. When I began my series of analyses comparing named ballots to anonymous ones, only about 20 percent of writers shared their picks voluntarily; now half of the voters do so without a FOIA request. Even most writers now support such a policy (at least in theory; a far smaller proportion apparently do so in practice). Transparency has come a long way.

Still, if I were Todd Helton and I were looking at these numbers, I’d have a hard time shaking the feeling that I got screwed. I don’t think that forcing writers to reveal their choices would have caused 11 of the 69 snubbed whose identities are secret to change their minds. Asserting that private ballots made an impact on this year’s results is far less clear than when Craig Biggio narrowly missed being elected in 2014, or Pedro Martinez’ detractors hid behind anonymity in 2015. But it’s close enough to wonder: What if?

Maybe it’s unfair to read negligence in how starkly anonymous voters’ choices diverge from those who put their names on their ballots. If so, there is an easy way to prove it: Open up all the ballots. Encourage every single member of the Cooperstown electorate to explain their choices; all of them should be more than qualified to do so. A requirement to reveal one’s choices would be a small price to pay for the honor of deciding whose bust adorns the sport’s most-hallowed halls. Baseball fans deserve a transparent election process, not a black ballot-box.

I don’t know where to begin if you the find the assertion that there is dissonance between the ideal of universal suffrage and how it works in the U.S. practice to be surprising. You can Google it.

Multiple members of the BBWAA have informed me that the organization has asked for all ballots to be made public, and that it is the Hall of Fame, not the BBWAA, who has refused that request. Still, the problem persists regardless of the source, and it’s reasonable to ask why so many writers decline to share their ballots if the organization supports such transparency.

These numbers include voters who revealed their ballots to Thibodaux but otherwise remained anonymous, which is why they are different than those cited below.

Given that voters are limited to a maximum of 10 votes per ballot, it could make sense not to vote for a shoo-in like Martinez and prioritize candidates for whom your support would make more of a difference. However, ensuring success for this strategy would presumably require publicly explaining your plan, lest a critical mass of other voters do the same thing because they all assumed that everyone else would wave him in.

It is possible that other writers will reveal their choices now that the results have been announced, including in two weeks when the BBWAA publishes the ballots for those who opted in to release them that way.

The trend holds even after adjusting for the potential bias of public voters selecting more players on their ballots.

Hi. HOF voter here. I keep my ballot private. Here's why: https://www.ocregister.com/2022/11/30/hoornstra-this-baseball-hall-of-fame-ballot-isnt-news/