Plunking Down a Plan to Curb Strikeouts

A modest proposal to bring more action back to baseball

For many years, Major League Baseball has been subject to constant hand-wringing about how to restore the game to its former glory. It’s a common observation that the modern style of play, featuring more strikeouts and fewer balls hit into the field, is less aesthetically appealing. Of course it’s impossible to disentangle how bothersome these contemporary trends are in a vacuum from the fact that so many of the baseball’s most-prominent voices won’t stop complaining that the game used to be better1 — sometimes I imagine John Smoltz bringing his curmudgeonly brand of color commentary to other events, like walking the red carpet at the Grammys and rambling about how none of this year’s nominees holds a candle to Pet Sounds — but most would agree that the product is more entertaining when the hitter is running to first than when they are trudging back to the dugout.

The problem with most plans to cut down on strikeouts is that the proliferation of swing-and-miss is borne not of contrarian stylistic preferences but of strategic optimization. Pitchers are throwing harder and using data to develop better pitches; hitters are prioritizing contact quality over quantity. Any proposal to make the game more exciting that does not fully reckon with the incentives that led to the current high-strikeout equilibrium (and the new ones it may create) is unlikely to work.

Consider the shift ban MLB implemented ahead of the 2023 season. To my surprise and chagrin, the new limits on defensive positioning have succeeded in meaningfully boosting the league’s batting average on balls in play. Yet anyone who considered the rules’ secondary goal of decreasing the the sport’s strikeout rate for more than a minute would have seen the obvious flaw: If hitters gain greater incentive to put more balls in play, pitchers have exactly the same extra motivation to avoid allowing them. What’s more, I found evidence that the shift ban is actually increasing strikeouts, because the new rules disproportionately benefit (and thus incentivize teams to play) hitters who swing and miss a lot.

The Shift is Hitting the Ban

There are many reasons why strikeouts are more common than they used to be. Pitchers at all levels are throwing harder every year, going at max-effort for shorter stints instead of pacing themselves to last deeper into games. Coaches are helping players develop better pitches based on what increasingly intricate data shows is most effective, then encour…

Short of revisiting fundamental assumptions like three strikes you’re out, I’ve long believed that the only surefire way to regulate strikeouts away is to restrict pitchers’ arsenals — an endeavor that would feel invasive and against the spirit of the game even if it were possible to implement fairly. (Though it’s a question of degrees, not principles, now that the league has started telling fielders where to stand.) No one seriously believes that MLB should ban sliders or establish a leaguewide speed limit.

But maybe there’s a more-natural way to make pitchers a little more hittable. What if we could subtly disincentivize velocity?

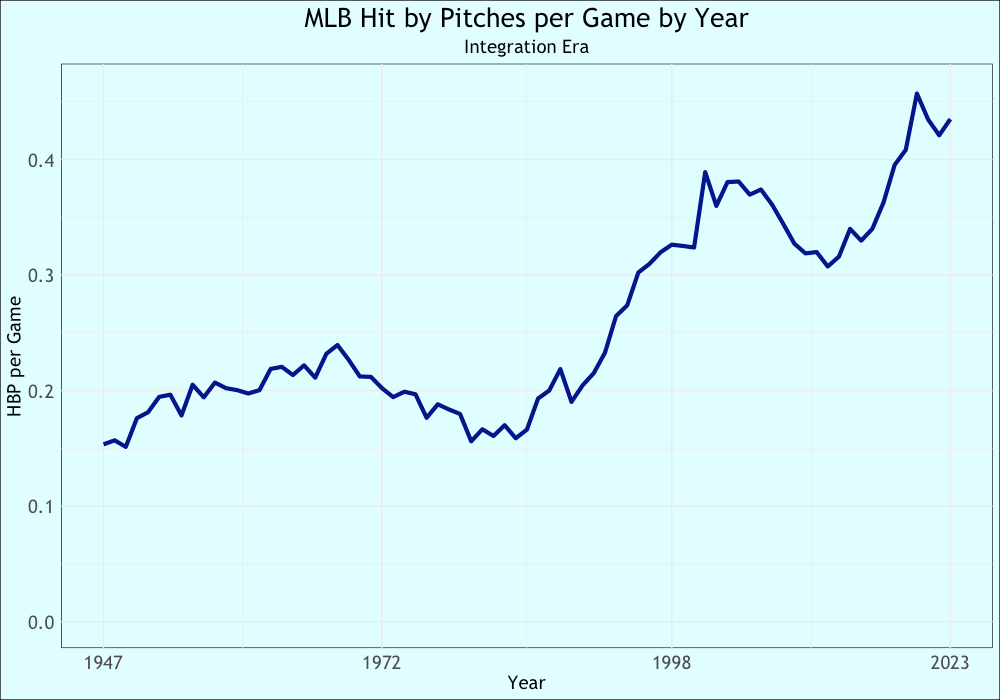

There’s been another trend in baseball over the last few years that has gotten less attention: hit-by-pitches have skyrocketed. MLB teams are averaging 0.44 HBP per game in 2023. That’s the second-highest rate in modern baseball history, trailing only the COVID-shortened season of 2020. It’s nearly double the league average from the year I was born. The league HBP/G was under 0.40 for 118 seasons from 1901 through 2018. Now we are on track to exceed that for the fifth year straight.

The last five years also happen to be the highest-strikeout seasons on record. It makes sense that these phenomena would overlap. The common conception of choosing between stuff and command is largely a false binary (like the narrative that sabermetrics works in opposition to scouting), but it’s fair to say teams are increasingly willing to trade a larger margin of error in pitch location, and thus a greater chance of the ball tailing into the hitter’s elbow, for more velocity and movement. The historical correlation between league strikeout and HBP rates — the “K-beans clustering,” if you will — is stark:

Correlation is not causation, and to be clear I am not alleging that strikeouts cause plunkings (or vice versa). Rather, I take this as evidence that they are two instrumental variables for the same high-level phenomenon: the degree to which the game is decided in the sixty feet, six inches between the rubber and home plate instead of the infield dirt or the outfield grass.

From the pitchers’ perspective, this tradeoff has been worth it. Comparing the 2023 league environment to when I was born in 1992, they have added roughly 15 strikeouts for each extra hit-by-pitch within my lifetime. But if you buy that the max-effort approach that leads to more whiffs also carries observable yet incommensurable drawbacks, a new avenue for rebalancing the game comes into focus. We don’t have to regulate pitch velocity. We just have to make throwing hard a bit costlier.

With all that in mind, my plan for cutting down on league strikeouts is to add the following to the MLB Rulebook:

A team may not hit an opposing batsman with a pitch more than once per game. Any subsequent instances of the same team hitting an opposing batsman with a pitch shall result in the immediate ejection of the offending pitcher, even if the prior hit-by-pitch was committed by a different pitcher.

It’s simple. It leverages an outcome that is already discouraged and penalized. There is ample precedent both for beanballs to result in ejections and for sports leagues to implement escalating in-game penalties. So far as I know, no one has ever proposed this before. And most importantly. it targets the specific behavior that has led to increased strikeouts in at least three distinct ways.

The most obvious impact of this rule would be to tilt the balance back from velocity towards command. A starting pitcher taking the mound in the first inning (probably) isn’t trying to drill the leadoff batter, but if they do, it’s effectively the same thing as a walk or a single. Under my proposal, if the first pitch runs too far inside, they’ve squandered their team’s margin of error right out of the chute. Each side starts the game a single mistake away from being a single mistake away from being in trouble. Would the pitcher be a little more inclined to attack hitters with finesse than to try to overpower them, at least for the first couple innings? You’d have to think so.

Once a team loses its sole legal HBP, they would play the rest of the game under the equivalent of an umpire’s warning, where even an accidental beanball will get you tossed. Perhaps that wouldn’t be a major deterrent to throwing at max effort for a pitcher who’s nearing their pitch limit or whose replacement is already warming up in the bullpen. But for a starter hoping to go deeper into a game or a closer coming in to forestall a late-inning comeback, an extra inch of locational precision might be more valuable than an additional tick of fastball velocity.

The Sho Must Go On

It was April 26, 2017, and Eric Thames was the toast of baseball. Thames was once known as a roster-fringe journeyman who had yet to distinguish himself at the Major League level. Now he had returned from three years with the NC Dinos in Changwon, where he ranked among the Korean Baseball Organization’s top three in both homers and OPS in each season and…

You could also see a shift in player evaluation. Consider Cincinnati Reds left-hander Nick Lodolo, who personified these trends in his MLB debut last season. The rookie ranked fifth in the National League (min. 100 IP) in strikeouts per nine innings (11.4 K/9) while also leading the Majors with 19 hit batsmen. (Only four other pitchers reached even 14 plunks; each threw at least 68 more innings than Lodolo.) He put the “effective” in “effectively wild,” posting a 3.66 ERA and earning multiple votes for NL Rookie of the Year. Yet he would have been ejected early in four of his 19 starts under this proposal, plus a fifth in which a reliever would have been thrown out for drilling a batter after Lodolo had used up the Reds’ freebie. There would still be a place in the big leagues for a pitcher as good as Lodolo — his ERA actually improves if you remove the times he continued to pitch after his retconned ejectable offenses — but approaches like his would be less valuable, and thus less common, if they came with a significant chance of getting tossed prematurely.

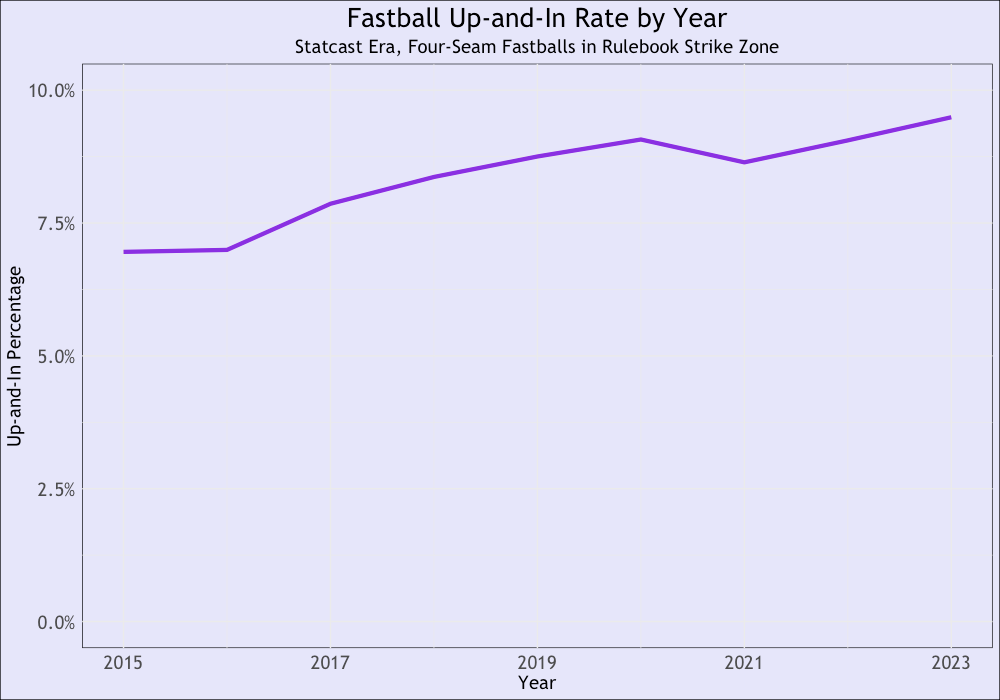

Beyond blow-and-go pitching philosophies becoming riskier bets, this proposal mitigates the advantage of velocity in another, more-specific way: throwing a fastball up and in would be more dangerous. To radically oversimplify modern views of pitching, high-and-tight is one of the most-effective locations for a heater, and arguably where velocity itself plays up the most. (Consider how much farther into your swing path you have to be to get the barrel through that part of the zone compared to attacking a pitch low and away.) The league has adjusted accordingly. The proportion of rulebook-strike four-seamers that hit both the upper and inner thirds of the zone is 36 percent higher this year than it was at the dawn of the Statcast Era.

There’s a good argument that baseball’s current strikeout-happy equilibrium ultimately boils down to ever-increasing fastball velocities. The proliferation of nasty breaking balls plays a role, as do batters’ willingness to trade contact for power, but even those are related to how little time a modern hitter has to identify and react to a pitch, à la If You Give a Mouse a Cookie. Meanwhile, more than two thirds of MLB beanings this year have come on pitches above the vertical middle of the strike zone, including 92 percent of offending four-seamers and sinkers. If pitchers have to think twice before throwing their fastballs where they feel the fastest, the compounding ripple effects will make it that much easier for hitters to square the ball up.

Finally and most subtly, ejecting pitchers more frequently would mean teams would need to make relievers more available. In many ways, bullpens have grown more flexible in recent years. Managers are increasingly willing to mix and match relievers based on matchups and situational leverage instead of waiting for an assigned inning. Yet the side effect of optimizing for short-stint nastiness is a greater need for rest — max-effort pitching is strenuous on the arm, and all else equal it takes more pitches to strike a batter out than it does to retire them on contact— so contemporary bullpen usage has come to mean heavy regimentation. Teams are increasingly reticent to let relievers throw three, or even two, days in a row.2 It’s not uncommon for a team to play a game with multiple bullpen arms on the active roster who are off-limits to pitch.

When Mike Trout Became the Best

In retrospect, what is the timeframe in which it was reasonable for a knowledgable baseball person to decide that Mike Trout was the best player in baseball? As in, when your reaction to hearing “Mike Trout is the best player in baseball" would have shifted from a scoff and an eyeroll to mere skepticism; and when “Mike Trout isn’t the best player in bas…

At my last count, MLB teams have reached the two-HBP-in-a-game threshold 8 percent of the time this year, including three or more (and thus multiple ejections) in a fifth of those instances. Obviously we would expect beanballs to decrease if this rule were implemented — that’s the whole point of increasing the penalties — but with that as our starting point, the average team would go to the bullpen earlier than expected a little over once every two weeks. That’s not enough to tear up modern bullpen-management philosophies, and I see a presumed increase in ejections as a flaw of this plan, not a feature. Still, if a manager needs more pitchers to get through a game, it would make it that much more difficult not to have a full stable of arms at their disposal. Thus teams should feel some pressure to help relievers pace themselves and save some strength in case they are needed on consecutive days.3

Cracking down on beanings would have other benefits too. It’s easy to forget that baseballs thrown at Autobahn speeds are dangerous. If increasing ejections goes against the principle of letting the best players showcase their skills as much as possible, that would at least be mitigated by fewer batters clutching their wrists on their way to the trainer’s table. It would also send a signal against the waning but still pervasive notion that aiming to hurt a hitter is an acceptable way to mete out justice for on-field slights.

The best argument I’ve come up with against this idea is that batters will lean into pitches to draw ejections. This is a fair critique, but it’s a manageable one. The league would have to pair this plan with clearer guidelines assessing batter intent and a directive for greater umpire scrutiny about crowding the plate; as obnoxious as this would be in practice, perhaps the batter’s attempt to avoid the pitch could be subject to replay review. (The head of the working group to hash out the implementation can be called the Chairman of the Ks and Beans Committee.) That said, I’m not sure that we would see significantly more plate-crowding than we do now, since the prospect of a free base is already a clear incentive for conniving hitters — rare are the occasions when taking the equivalent of an automatic walk isn’t helpful to the batter’s team.

Is Catcher Framing Cheating?

On September 15, 2010, New York Yankees shortstop Derek Jeter pretended to get hit by a pitch.

I don’t think the Commissioner’s Office needs to meddle in the ecosystem of the game. The balance between hitting and pitching is always shifting; teams constantly innovate, adapt, and overcorrect. But I respect the notion of interfering to make the on-field product more entertaining, and if the league feels pressure to curtail its soaring strikeout rates, they might as well do it in a way that will actually work. I believe cracking down on hit-by-pitches would make the game better. Or MLB can keep futzing with the rules without considering the incentives they’re creating, but that won’t amount to a hill of beans.

I have argued for literally a decade that anyone who’s really worried about young people losing interest in baseball would be trying to sell the virtues of the modern game instead of constantly talking about how much it sucks. Or at least be more worried about how the increasing cost of youth baseball, contraction of the minor leagues, and byzantine blackout rules for streaming are denying countless kids the chance to fall in love with the game.

I have a vivid (albeit possibly warped) childhood memory of reading about a reliever rehabilitating from an injury, in which a coach described pitching two innings on back-to-back days as part of the standard recovery process. How times have changed!

While we’re at it, we should revoke the abominable change to place a runner on second base at the start of each extra inning. In addition to being an aesthetic affront to baseball and violating the rhythm of how runs are scored, reining in the right-tail outcome for how many innings a bullpen might have to cover enables the short-stint bullpen usage and thus increases the strikeout-heavy style of play that the league now seeks to curtail.

I was thinking your idea would be to put a hit batter on second instead of first. I think I like that idea better because as you alluded to, it punishes pitchers more equally. With the ejection rule, starting pitchers have a strong advantage because they're more likely to have a HBP forgiveness available. More pitcher ejections could also lead to roster balance issues.

Found your piece on Notes. Very interesting stuff. I believe pitch velocity is an issue on a range of fronts, but never connected the dots to potential rules changes. Gonna mull on this on.