Unpacking the 2026 Hall of Fame Results

Five takeaways from this year's Cooperstown inductees and voting trends

The Baseball Writers Association of America have revealed their annual selections for the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Joining Jeff Kent (who was already selected by the Era Committee) on the podium for the induction ceremony this summer will be two star center fielders who finally reached the 75 percent threshold for the game’s highest honor: Carlos Beltrán and Andruw Jones.

There is plenty to say about the new inductees’ incredible careers, but I have written about them both before, and I am not particularly interested in venerating Jones any further. But there are other subtler trends among the voting results that are illuminating for interested fans. Here are my five biggest takeaways about the Cooperstown selection process as we start looking ahead to 2027 and beyond.

Content warning: domestic and sexual violence

A new tolerance for cheaters…

The modern electorate’s approach to cheating could charitably be described as idiosyncratic. Mike Piazza is in the Hall of Fame despite having admitted to using androstenedione, and several other recent inductees are commonly suspected or assumed to have used performance-enhancing drugs as well. Other players have been less lucky, as their doping became the defining feature of their respective candidacies. Like Rafael Palmeiro, a member of both the 3,000-hit and 500-homer clubs who failed to maintain the requisite five-percent support to even remain on the BBWAA ballot. Or Mark McGwire, who never reached even a quarter of the vote despite the fact that the commissioner had contemporaneously condoned his drug use.

To me, Carlos Beltrán’s involvement in the Houston Astros’ sign-stealing scheme was more objectionable than his peers using PEDs: The connection between the cheating and the outcome on the field is clearer, and there has never been any ambiguity that using technology to steal signs is illegal. (Though I would have voted for him regardless.) Clearly the electorate disagrees, since Beltrán is getting his flowers while Alex Rodríguez has barely half the support (40 percent) required for enshrinement.

Still, I wonder if Beltrán’s induction will spark a reconsideration. If the sole player explicitly named as responsible after the commissioner’s office’s monthslong investigation into the Astros’ sign-stealing scandal can receive the game’s highest honor, what about the raft of other recent stars who allegedly cheated but were never found to have violated MLB’s collectively bargained drug policy? Many voters today make a distinction between those who juiced before the league had a real testing and enforcement program and those who violated it, and since Beltrán was not suspended for cheating he is nominally more comparable to the former group. But the scandal cost him his job as manager of the New York Mets before he had coached a single game, which was widely understood as a de facto punishment.

One of the strongest arguments for letting dopers into the Hall is that the typical recourse for PEDs is not a lifetime ban. Palmeiro and Rodríguez, for example, each played the Majors again after they served their time. Even sure-to-be controversial upcoming candidate Robinson Canó, who missed a combined 242 games after testing positive for banned substances on two separate occasions, later returned to the big leagues in good standing. By contrast, Beltrán has not coached an MLB game since he lost his nascent managerial job,1 so I’d argue that he is effectively closer to being on the league’s permanently ineligible list than any recent candidate who’s been kept out due to drugs.

I’m not holding my breath. If the BBWAA’s views on inducting (alleged) cheaters into Cooperstown were consistent, we wouldn’t be in this mess in the first place. But if the writers were looking for an off-ramp from their incoherent approach to PEDs, Beltrán’s election provides a potential reset button. At the very least, it clarifies that the voters’ stridence is specifically about juicing, not other forms of cheating, so perhaps we won’t see similar efforts to retroactively punish other recent contemporaneously abided yet ethically questionable behavior like pitch framing and grip enhancements.

And speaking of inferring moral judgments…

…and abusers.

On December 25, 2012, the police were called to Andruw Jones’ house. His wife told police that Jones had dragged her down a flight of stairs and threatened to kill her. He was arrested for battery and later pled guilty to the charges; there is no need here to say “allegedly.” Today the man who committed these heinous acts was granted the highest honor the game can bestow.

Our society and the sport purport to take intimate-partner violence seriously. I suspect that virtually every individual BBWAA voter — even the ones who voted for Jones, or Omar Vizquel, or Manny Ramírez, or Francisco Rodríguez — would tell you that they do, too. They might say that recognizing Jones’ achievements and condemning his personal conduct are not mutually exclusive, even as such veneration of an athlete’s performance inevitably bleeds over into adulting their character. I used to hold that view, so I get it. But the more I think about the pain that doing so causes to survivors of IPV, and that selective tolerance for such acts gives other abusers hope that their crimes will be similar swept under the rug, the harder it is for me to understand voters’ eagerness to separate the player from the man. Grosser still is the philosophy, implicit among the dozens of voters who stopped supporting Vizquel after the disturbing allegations against him arose yet continued to check Jones’ name (and even explicit among some writers who in their ballot explainers), that such issues are irrelevant if a player is good enough — if they have enough home runs or Gold Gloves, their other sins are washed away.

Hall of Fame elections aren’t political campaigns, and there is no consideration towards choosing a lesser evil for the greater good. Is making our already-flawed collective list of the best players of all time marginally less incoherent really worth the moral compromise? Seventy-eight percent of voters said yes.

It’s a particularly frustrating outcome for two reasons. First is that Jones received disproportionate support from newer voters. Of the 37 BBWAA members who cast a ballot for the first time in 2026 and who have revealed their picks, 34 checked off Jones’ name. We as a culture like to think that we are moving away from countenancing domestic violence — that attitudes change as old boys’ clubs (like the Cooperstown electorate) get younger and more diverse. Yet the BBWAA is heading in the other direction. Which doesn’t bode well for the next few years as abusers like Miguel Cabrera and Aroldis Chapman reach the ballot.

More importantly, Jones represents an inflection point in how voters interpret the so-called “character clause,” because there is no recent precedent for the BBWAA electing an admitted domestic abuser. Yes, there are plenty of scumbags in the Hall of Fame, and a number of objectionable candidates over the last few years have coincidentally fallen short for less-important reasons. But Jones is the only player to be selected to Cooperstown despite facing (let alone having pled guilty to) allegations this detailed and gruesome since MLB instituted its first domestic violence policy in 2015. The only player in my lifetime I can recall the BBWAA selecting amidst remotely comparable allegations is David Ortiz, whose financial dispute with his ex-partner led to mutual restraining orders and accusations of threats and intimidation. Unless I’m forgetting someone — a crucial caveat as such stories do not always make headlines2 — that’s it. Bobby Cox got in via a different selection process, the less-transparent Eras Committee. Roberto Alomar and Kirby Puckett were inducted before their worst scandals broke.

I’m under no illusions that Johan Santana went one-and-done because of his sexual battery accusation instead of his simply being underrated, or that Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens have been kept out due to their domestic violence and child-grooming allegations, respectively, rather than PEDs. Yet even if unintentionally, the writers had set a precedent of generally keeping players accused of such heinous things out of the Hall of Fame. In electing Jones, the BBWAA didn’t merely decline to draw a moral line. They retreated from the one they had already effectively established.

I suppose the silver lining is that Jones’ on-field accomplishments were clearly worthy of Cooperstown, so if this collective Andrew Berry-esque disinterest in athletes’ personal conduct is a sunk cost, then at least his getting 78 percent of the vote suggests that player-evaluation standards have improved since he earned a mere seven percent support in his 2018 ballot debut. But he’s not the only manifestation of that…

Increased hope of future inductions…

The relative dearth of strong candidates on this year’s Cooperstown ballot is bittersweet. On the one hand, it’s a sign that the backlog from the writers’ notorious stinginess is finally clearing up. On the other, it’s a reflection of how many worthy candidates from recent overcrowded ballots were prematurely dropped from consideration after failing to reach the five-percent threshold for another shot. However you slice it, the manageable crop of returning names, combined with a conspicuously shallow slate of newly eligible candidates and the curious phenomenon of critical masses of veteran sportswriters sometimes deciding that players have gotten magically better many years after they retired, made this ballot a great opportunity for holdovers to consolidate their support.

After Beltrán and Jones, the top finisher was Chase Utley. I remain flummoxed that Utley, who was an inner-circle great in his prime, will require (at least) a fourth try to earn his flowers. The silver lining is that, after reaching 59 percent in 2026, he is on track to get in soon. Every candidate to get 57 percent of the vote on their third ballot has eventually reached 75 percent, and the only player to earn 43 percent support on their third try who hasn’t gotten into Cooperstown one way or another is Omar Vizquel (whose candidacy was subsequently tanked by off-field scandals). Utley will be the headliner on the 2027 ballot, and another increase as big as the one he got this year would be more than enough to put him over the line in 12 months.

Arguably the biggest narrative shift came belongs to Utley’s teammate, Bobby Abreu. Abreu, who initially barely cleared the five-percent threshold to remain on the ballot, leaped from 20 percent in 2025 to 31 percent in 2026. In practical terms, that’s not huge — especially with only three more years of eligibility remaining. But by vibes, which if we’re being honest is what Cooperstown voting largely comes down to, that feels like the difference between a marginal candidate and a legitimate consideration. Most players who exceeded 30 percent on their seventh ballot and weren’t dragged down by character-clause questions have gotten in eventually. Abreu is now notably ahead of fellow outfielder and eventual inductee Larry Walker’s trajectory. Fellow Phillie Jimmy Rollins also took a notable step forward on his fourth try on the ballot, going from 18 percent last year to 25 percent now. Moving around the horn, Dustin Pedroia (21 percent) and David Wright (15 percent) nearly doubled their respective shares from a year ago.

There are some big gainers on the pitching side, too. Félix Hernández saw his support shoot up from 21 percent in his 2025 debut to 46 percent now; there is no precedent for a candidate reaching that level on their second ballot without getting voted in later. Andy Pettitte, whose support had already doubled from 14 percent to 28 percent last year, nearly lapped himself again with 48 percent in 2026. Even with only two years of eligibility left, nearly every candidate who cleared a third of the vote on their eighth try (as Pettitte did comfortably) is now in Cooperstown. Most of the exceptions are juicers, which also applies to Pettitte, though the more-than-threefold increase in his support over the last two years implies that voters are more open-minded about him than Bonds or Clemens, so he has a real chance. It also helps that we’ve reached an inflection point for modern aces…

…especially for pitchers.

A year ago, when CC Sabathia made it into the Hall of Fame on his first try, I observed that he was the worst pitcher the BBWAA had elected in my lifetime. (This was not a dig at Sabathia, who was clearly deserving.) I posited that his induction represented an inflection point for Cooperstown pitchers:

Lesser pitchers have gotten in in the past or via the Veterans Committee, but the BBWAA’s recent standards have been incredibly high. I would argue that, given how the league has changed and pitching strategies have evolved, they have been impossibly high for modern starters. It took Mussina six elections to get in. Blyleven had to wait until his 14th try. Kevin Brown, David Cone, and Rick Reuschel were one-and-dones. There ended up to be good reasons not to vote for Curt Schilling, but I’ll never understand why he wasn’t an easy yes before that.

Sabathia getting in on his first ballot with a resounding 87 percent of the vote feels like the writers planting a flag to modernize their standards.

It’s hard to say for sure what drives momentum in Cooperstown campaigns, though this year’s surges in support for Hernández and Pettitte offer early support for my theory. Yet the biggest evidence for the electorate’s evolving mindset is the support for Cole Hamels. Hamels was the definition of a modern ace, but changes in pitcher usage and the league run environment rendered his numbers fairly pedestrian by the Hall’s standards. He’s got a long way to go from his initial 24 percent support to 75 percent, but there is plenty of precedent for players who start out in that range getting in later. And looking over the list of starters who went one-and-done on recent ballots, the fact that he so comfortably cleared the five-percent threshold to maintain eligibility is itself a sign of progress. We’ll see if this group continues consolidating support next year — and whether their success will extend to longtime holdover Mark Buehrle and 2027 newcomer Jon Lester.

Finally, checking in on the beat I’ve covered for years…

Anonymous ballots are at it again

The secret ballot is a foundational principle of representative democracy. Ordinary citizens must be free to express their political desires without fear of intimidation. This does not apply to the BBWAA electorate. Voting for the Hall of Fame is a privilege, not a right. The honor is bestowed only upon veteran sportswriters, who definitionally both possess expertise in analyzing and communicating their opinions about baseball and a journalistic responsibility to disclose their roles in creating the news they cover. But don’t take my word for it: the BBWAA members themselves have repeatedly voted to make all their Cooperstown votes public, only to be overruled by the Hall of Fame’s leadership.

There is a persistent, conspicuous difference in results between writers who reveal their ballots and their more-secretive peers. In the early days of social media, it was possible to chalk this up to demographics: the voters who took the time to post their selections on Twitter were probably younger and more interested in modern analytics than their less-online peers. Nowadays, when the organization has voted multiple times to make writers’ picks mandatory and ballot contains a checkbox asking the electorate to opt into sharing them with no further effort required, that’s a tougher argument to make.

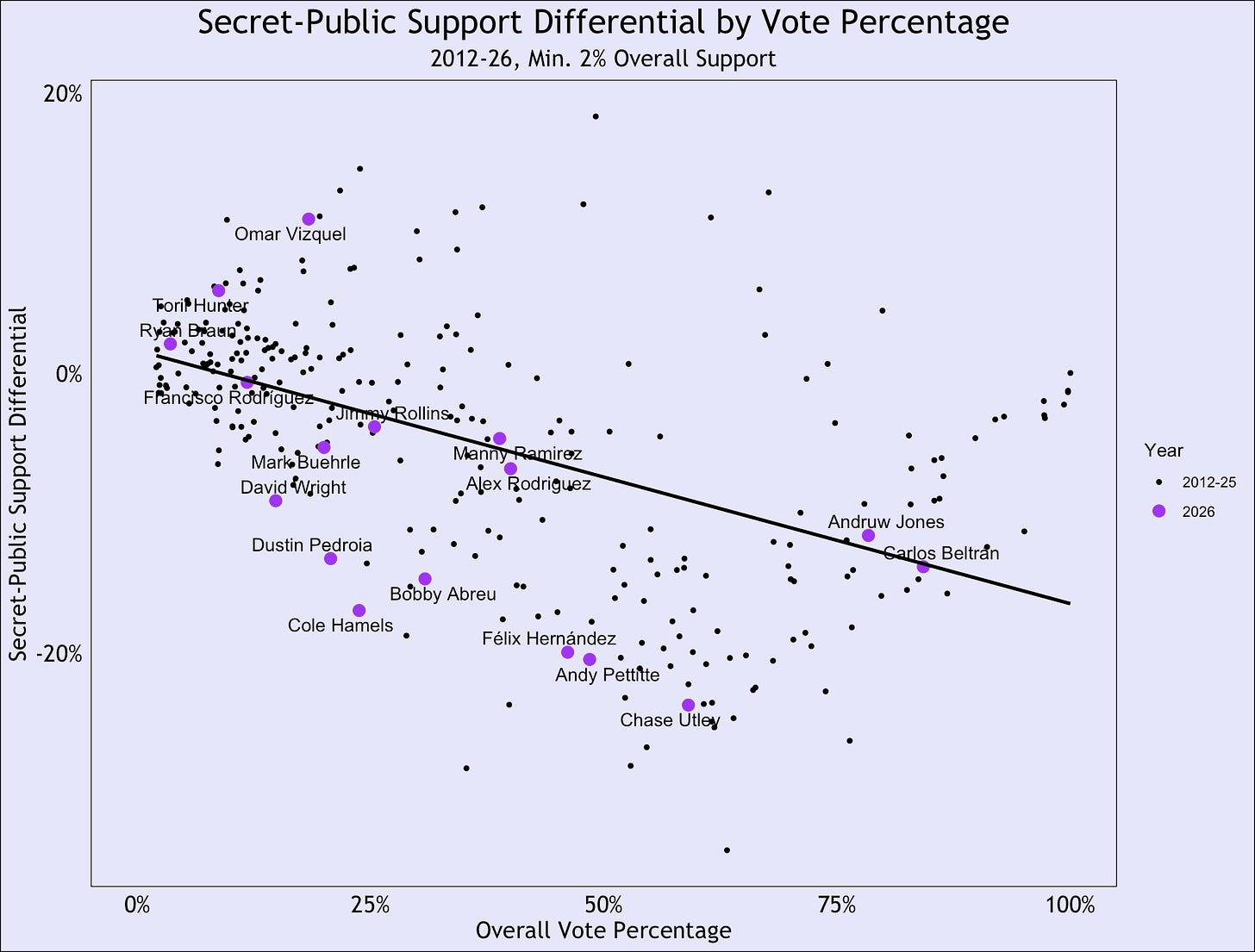

The 232 ballots that were revealed before the election, as diligently recorded by Ryan Thibadoux, Anthony Calamis, and Adam Dore via the BBHOF Tracker, do not represent the whole group of transparency-oriented voters; the BBWAA will officially release the full list of shared ballots in a couple weeks. But comparing the preliminary results from public vs. anonymous voters yields some familiar trends:

Those who shared their picks checked off more players, at an average of 6.4 voters per ballot compared to their secretive peers’ 5.0.

Anonymous voters were more likely to snub the two inductees, leaving both Beltrán (16 percent vs. 9 percent) and Jones (22 percent vs. 16 percent) off their ballots at notably higher rates.

The 24-percent delta between Chase Utley’s share among public (70 percent) and private votes (46 percent) would be tied for the ninth-largest since the BBWAA began publishing ballots in 2012…with himself a year ago (among a few other instances).

The player who got the biggest relative boost among anonymous voters? Omar Vizquel, who was named on 13 percent of public ballots but 24 percent of secret ones. I wonder if his supporters were simply ashamed to have their names attached to a candidate who has been accused of such horrific things.

While the ultimate outcome was the same among both electorates, it’s worth noting that anonymous voters once again voted objectively worse than their more-transparent peers. The top ten players on the ballot by rWAR all earned more support from public ballots than secret ones. More damningly, the same can be said for the top 12 vote-getters — meaning private electors’ picks (or omissions) were less-defensible according to the voters themselves. Which is in keeping with a long-established inverse correlation between how qualified the writers think players are and how willing their naysayers were to own up to their contrarianism.

I’ve said it before, and until either ballot-sharing becomes mandatory or this phenomenon abates, I’ll say it again: If you are a veteran sportswriter who communicates your thoughts on baseball for a living and you are not confident that you can explain your Cooperstown ballot in a logical way, you voted wrong.

Though the Mets eventually re-hired him as while a special assistant to the front office.

It’s also worth noting that same people who determine what is newsworthy also decide who gets into the Hall of Fame.

When it comes to the Hall of Fame, if you want to leave out half of the record books for alleged-or-proven PED usage (and/or character issues), that's fine. Then I would petition for the removal of the FIRST player ever elected to the Hall. That would be noted bigot and hate crime purveyor Ty Cobb. Simple as that. You got a character clause, make it retroactive.

Now, the attitude I PREFER is to can the character clause. Because there is a PLAQUE, and the PLAQUE immortalizes the story of said player. So the plaque for Barry Bonds would say:

-Greatest player of his, and maybe any generation.

-All-time leader in home runs and walks.

-Only player to hit 500 home runs and 500 stolen bases.

-Leaked Grand Jury testimony revealed he was using PED's.

-Infamously prickly and unpleasant with teammates and the media.

And with Andruw Jones, you'd say:

-One of the greatest centerfielders of all time.

-Cumulative stats of (not looking it up, whatever)

-Defensive wizard in the outfield.

-Domestic abuse details.

You get the highest honor any baseball player can receive. But for the rest of your life, the sins you've committed stare back at you. And the fans are allowed to invent their own legacy (and let's face it, they'll probably be forgiving), but all the information is in one place.

I also would have voted for Curt Schilling to be in the Hall of Fame. And his plaque should have read:

CURT SCHILLING: Massive Jerk.

That's it. That's the plaque.