My 2026 Baseball Hall of Fame Mock Ballot

Picking eight worthy players is easy. Finding two more is harder.

Conversations about the Hall of Fame should start from a place of positivity. This is both my longstanding view of the Cooperstown selection process, as I believe we ought to focus more on finding reasons to put players in rather than looking for excuses to keep them out; and the premise of the essay you are about to read. But we must start by acknowledging a harsh truth: This year’s slate of nominees is the weakest of my adult life.

We can quantify just how shallow this class is. For those who lean on sabermetric evaluative frameworks to fill out their Cooperstown ballots, 60 wins above replacement is the typical standard at which a candidate becomes a clear yes. There are just seven nominees on the 2026 Baseball Writers Association of America ballot with 60+ career rWAR, the fewest since 2008 — and that includes two who are barely over the line at 60.2. The 11 players with 50+ rWAR (around the threshold for a borderline inductee) are the fewest since 2012.

The slate’s underwhelmingness is largely a function of how last year’s vote went. The usually stingy BBWAA electorate has corrected course of late, inducting three players two years in a row. This has helped mitigate the backlog of worthy candidates that plagued recent ballots. On the flipside, three players I definitely would have voted for (Russell Martin, Brian McCann, and Ben Zobrist) fell off the ballot, having failed to reach the five-percent threshold to get another try.

The holdovers are joined by a notably shallow crop of first-time-eligible candidates. This year is just the second time a ballot has contained fewer than three newbies with 40+ career WAR since 1987. Looking for something more sophisticated than raw WAR totals? Per Adam Darowski’s Hall Rating, which is standardized such that 100 is the threshold for induction, only two debutants have scores above 60. By Jay Jaffe’s JAWS system, just two ballot rookies come within 20 wins of the Cooperstown average for their respective positions — the fewest since 1978, and a stark drop-off from the 11 such players who were considered for the first time in 2025. (Which, in turn, was tied for the most since Jackie Robinson’s second season with the Dodgers.)

The upshot is that, as a vocal Big Hall guy who routinely advocates for more candidates than any writer is allowed to vote for, using up each of my (hypothetical) 10 allotted slots is unusually challenging this time. A year ago, there were 21 players on the ballot whom I thought merited serious consideration. A few minutes into sitting with the 2026 slate and considering their respective candidacies in the most-favorable lights I could, there were only eight names I was enthusiastic about checking off.

Yet Friend of The Lewsletter and actual Hall of Fame voter Sam Miller has convinced me that it is a voter’s duty to use all 10 of their available slots. In an essay last year explaining how he filled out his ballot that has stuck with me ever since, Sam articulated two critical asymmetries about the Cooperstown selection process. First, induction into the Hall is permanent, yet rejection is transient. There is effectively no limit to how many times a prior snub can be reconsidered. Second, fans are ultimately happier when beloved players who may fall short of conventional standards get in than when candidates on the bubble are turned away. “When you accept this,” Sam wrote, “there’s really not much point being a hard-line gatekeeper”:

Nobody has been “rejected” by the Hall of Fame, and so nobody who isn’t in sets the standard for who shouldn’t be in. They’re all just still waiting. Scores of long-retired players who we don’t currently think of Hall of Famers will be inducted someday, and then they’ll be Hall of Famers, helping define the “standards.” There’s no point saying “I can’t vote for Bobby Abreu if the superior Dwight Evans/Kenny Lofton/Jim Edmonds isn’t in.” It’s true that Dwight Evans is still waiting, but the future is long. He’s just not in yet. Betcha he’ll get in. Betcha they all get in.

The real consideration for a borderline player, Sam explained, “is whether I want to help him or slow him down.” I’m sold on this framing. And especially since the stress of going through an election cycle is so great that it is actuarially measurable for candidates on the bubble, I would rather let them in as quickly as possible. So I intend to use all 10 of my allotted (hypothetical) votes.

In recent election seasons, I have spilled thousands of words expounding upon my approach to the Hall of Fame and why each of the players I would vote for meet my standards. I may not have an actual vote, but during my years of not being allowed to write about baseball, being part of the annual Cooperstown conversations is what I missed most. Plus, given my stridence in calling for all Hall of Fame ballots to be made public, it seemed only fair to model the behavior I expect from real voters.

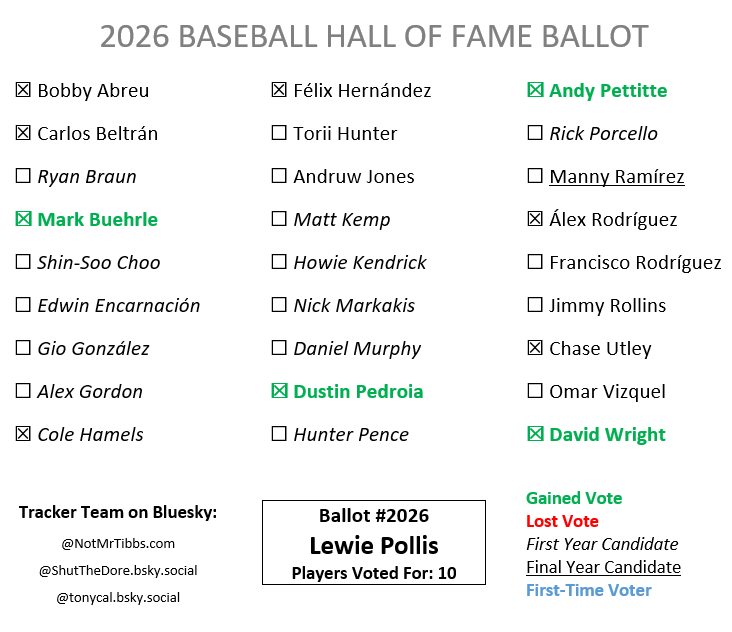

Most of what I have to say about this year’s best candidates has already been said. Of the 10 players I checked off on my mock ballot last year, five are still eligible in 2026: Bobby Abreu, Carlos Beltrán, Félix Hernández, Alex Rodríguez, and Chase Utley. There are two returning candidates whom I have supported in the past, and omitted in 2025 only because of the 10-vote limit: Mark Buehrle and Andy Pettitte. I have written plenty about all of them before, especially Utley, so I won’t rehash those arguments again here. That makes seven easy yeses from me.

You have probably inferred that I don’t consider doping or cheating to be a dealbreaker. To briefly summarize an argument I’ve made in depth before, I see these are sins against the sport, not society, and therefore it is ahistorical and unnecessary to retroactively penalize behavior that the league contemporaneously abided.1 By contrast, given how easily adulation of athletes’ on-field accomplishments bleeds into personal veneration, and that selective outrage undermines the sport’s occasional gestures towards taking the issue seriously, I am an automatic no on any player facing credible accusations of intimate partner violence. (If this hasn’t been your philosophy in the past, it’s not too late to start now.) Which this year applies to an unfortunately large group of candidates whom I would otherwise support: Andruw Jones, Manny Ramírez, Francisco Rodríguez, and Omar Vizquel.

The easiest addition to my list this year is Cole Hamels. Establishing new standards for starting pitchers in an age when reduced workloads put historical counting-stat benchmarks out of reach for even the game’s generational talents is still a work in progress. In the meantime, my suggested heuristic is that any modern starter who isn’t an obvious no should probably be in, and any borderline candidate ought to be an easy yes. Hamels was a true ace who ranks as one of the Top 60 pitchers of all time by Hall Rating and among the Top 75 by era-adjusted JAWS, and authored one of the greatest runs of playoff pitching of my lifetime en route to a 2008 World Series championship. CC Sabathia’s first-ballot election last year was a promising first step. Hopefully Sabathia’s success greases the skids for some of his contemporaries.

But what about the rest of the slate?

In my prior mock-ballot write-ups, I haven’t focused much on the candidates who fall short of my bar for induction. Yet my initial list exhausted only eight of the 10 votes I plan to use. With two spots left on my ballot and 15 remaining candidates I had initially dismissed, I faced a different and more-challenging question than the usual premise of this exercise: Who among the players I snubbed is the easiest to talk myself into voting for?

At first glance, the first name left alphabetically is the best of the remaining first-time candidates. Ryan Braun has the makings of Hall-worthy résumé: he was an MVP (and a three-time top-three finisher), a Rookie of the Year, a five-time Silver Slugger, and a six-time All-Star. His top similarity-score comp on Baseball-Reference is in the Hall. Had he sustained his prime a couple years longer or provided positive value in the field, there would be more than a perfunctory case for his bust to adorn the Plaque Gallery. Yet Braun’s conduct as he contested his first suspension for PEDs, up to and including slandering the integrity of the urine test collector, was reprehensible. As a Jewish person in 2025 I have little patience for public figures making disingenuous claims of antisemitism to further their own self-interests. If he were actually a worthy candidate, I would think more deeply about whether Braun is merely a schmuck whose accomplishments can be compartmentalized from his character, or whether (like Curt Schilling) his behavior rose to the level of fully disqualifying. For this exercise, when I’ve already established that I don’t think he is good enough and am considering him as a mere gesture of goodwill, it’s a distinction without a difference.

For much of his early career (until his legal issues arose), Shin-Soo Choo was my favorite player. Three-time 20-20 players don’t grow on trees, and you could make a Ben Zobrist-esque argument that he deserves recognition for embodying an evolution in the game (the $130 million free-agent deal he signed 2013 was understood as a sign that the industry was finally valuing on-base skill properly). I’d enjoy the poetic justice of the most-snubbed All-Star candidate of his generation — he made his lone appearance at age 36, in what was merely his seventh-best season — earning the sport’s top honor. Yet he had only about three-and-a-half great years, and a similar number of merely good ones. I’m trying to avoid tit-for-tat comparisons like Choo can’t be in while Bobby Abreu is out, but Abreu’s contemporaneous candidacy is a template for how a convincing case for a solid-at-everything, underrated-in-his-day outfielder could look. Choo falls well short of that.

Edwin Encarnación is the kind of guy I’d love to find room for. There is no conventional case for him. His 424 home runs aren’t enough for a headlining statistic, he came well short of the effective 2,000-hit minimum, and no major WAR model has him ever eclipsing even five wins in a season. But he wasn’t that far off of some milestone numbers, and he’d probably have gotten there if he weren’t such a late bloomer — he had eight straight seasons with 32+ homers despite not topping 26 dingers until he was 29. And gosh, was he an exciting hitter. I previously argued that his longtime lineup-mate, José Bautista, should be a Hall of Famer. Encarnación didn’t quite reach the same heights, and on a deeper ballot I probably wouldn’t give him a second thought. This year, with spots to spare, it would be fun to offer him a salute.

Did you remember that Gio González once won 21 games in a season? Me neither. I admit that my reflex was that was he was a borderline candidate…to be on the ballot at all. But I realized that believing in laxer standards for starting pitchers, as I do, was incompatible with dismissing his case out of hand. González had maybe two ace-worthy seasons, and a few more really solid ones. Is that what greatness looks like for starters these days once you get past the inner-circle Scherzer-Verlander tier? Or was he just a reliable mid-rotation guy who punched above his weight for a couple years? Or is that, in turn, what second-rung greatness looks like for modern starters? You could liken González’ career to Buehrle’s, as a fellow lefty who was better than you remember…though Buehrle threw 70 percent more innings and was also one of the best-fielding pitchers of all time. I don’t think González is a Hall of Famer. But if we’re serious about setting new standards for starters, there are worse uses of a token vote.

In his prime, Alex Gordon was one of the best defensive players in the game (relative to his position), a good hitter, and arguably the face of one of the most-iconic championship cores of the 21st century. From 2011-14 he ranked tenth in the Majors in fWAR and won the first four of his eventual eight Gold Gloves. Had he sustained those superlatives for a few more years, or played a tougher defensive position, he would have an interesting case. Winning eight Gold Gloves is nothing to sneeze at (hold that thought for the next paragraph) but it means less when he did it as a left fielder, especially since there are two other players on the ballot who won even more times in center.

One of them is Torii Hunter. I confess I’ve been confused that Hunter, who depending on your preferred flavor of WAR never had a single five-win season, perennially picks up just enough support to remain on the ballot after Jim Edmonds and Kenny Lofton were one-and-dones, but I tried to go into this exercise with an open mind. Before the disqualifying allegations against him came to light, I had argued that Omar Vizquel was a Hall of Famer, because in my book being one of the greatest defenders of all time is sufficient for induction no matter how he fared in the batter’s box. Hunter won nine Gold Gloves while playing a premium defensive position in center field. Wouldn’t the same logic apply to him? Just 20 other players in history have won at least as many Gold Gloves at a position harder than first base, and the only ones who aren’t in Cooperstown are either not yet eligible or currently on the ballot. Yet it’s tough to argue that Hunter set the standard for his generation of center fielders (as Vizquel did for shortstops) when three of the six outfielders in history to win even more Gold Gloves were his contemporaries: Ken Griffey Jr. and Andruw Jones’ careers overlapped with Hunter’s, and Ichiro shared the American League honors every single year Hunter won plus one more. And while I typically prefer retconning awards to be a strictly positive exercise, it’s worth noting that Hunter won in several years when he rated as a below-average fielder by the then-state-of-the-art defensive metrics, and a modern electorate would likely have given him only two or three. Overall it’s a tenuous case, but in a year when I have spots on my ballot to spare, I won’t rule him out.

I have long believed that Cooperstown candidates should be considered in terms of whatever statistical frameworks were most-favorable to them, even if they are now antiquated. In Matt Kemp’s case, that means giving him some credit for how he rated in a now-deprecated version of WAR. As Neil Paine recently noted, Baseball-Reference contemporaneously valued Kemp’s 2011 season as worth 10 wins above replacement. Reaching 10 WAR in a single year, even once, is a marker of what sports statisticians call “signature significance,” in that almost every hitter who’s ever done it is a Hall of Famer. Subsequent updates to Baseball-Reference’s formulae have knocked his total down to eight WAR (in line with FanGraphs’ model). He’d be a negative outlier anyway: While every other player on the list had at least one more six-win season, 2011 was the only time Kemp reached even five. It’s a flimsy foundation for a Cooperstown résumé, but according to a commonly accepted metric of his time, Kemp’s best year outshined all but one other candidate’s on the ballot (Alex Rodríguez). That has to be worth something.

Howie Kendrick’s memory will live forever via his decisive go-ahead home run in Game 7 of the 2019 World Series. He was a good hitter and a fun player. He is not a Hall of Famer.

Nick Markakis was a consistently tough out and one of the most-durable players of his era, averaging 154 games a year through his age-34 season. He was a roughly league-average player in the aggregate, with a prorated WAR-per-game below Rabbit Maranville’s. He is not a Hall of Famer.

Daniel Murphy had a legendary run in the 2015 playoffs and two pretty good years after that.2 He is probably the worst player on the ballot, and I’ll remember him most as a trailblazer for bigotry: In an unfortunate presage of the recent clubhouse backlashes against ballpark Pride Nights, Murphy’s takeaway from a team meeting with league ambassador for inclusion Billy Bean was to “disagree with the fact that Billy is a homosexual.” He is not a Hall of Famer.

The last cut from my deserving-candidate list a year ago was Dustin Pedroia. My gut says that Pedroia belongs in Cooperstown, but the more I try to rationalize that the less confident I am. He was pesky at the plate but finished well shy of 2,000 hits. He was speedy but never stole 30 bases in a season. He played a terrific defensive second baseman in an era when that wasn’t distinctive. He was the face of some great Red Sox teams but wasn’t particularly impactful in those playoff runs (.687 OPS in 51 postseason games). The knee injury that effectively ended his career is the kind of romantically tragic what if? that captures fans’ imaginations, and a few more decent seasons would have bolstered his case, but by that point his relatively brief run of superstardom was already long behind him. Is the alternate timeline where he stays healthy that much more compelling than it is for, say, Grady Sizemore or Troy Tulowitzki? Still, it’s hard to say anyone else in this group had a better career than Pedroia did, and he just feels like a Hall of Famer. Does that count for anything?

I would love to make a contrarian case for Hunter Pence, an incredibly fun and fully unique player, to have a place in Cooperstown. Unfortunately I can’t think of what it could possibly be.

I’ll give Rick Porcello this: He won a Cy Young award, which is more than you can say for anyone else on the ballot save Félix Hernández. However, that was the only year when you could call him even a Top 25 pitcher in the game. His 4.40 career ERA was worse than league average after adjusting for the context in which he played, and is over a half-run above the next-highest on the ballot.3 I guess a vote for him could help shift the Overton window and make Buehrle and Pettitte look better by comparison.

Jimmy Rollins received 18 percent of the BBWAA vote last year, making him the best-performing candidate whom I previously omitted for reasons besides scandals or ballot space. As a Phillies fan I’d love to vote for Rollins, though I haven’t quite figured out how to get myself there. He was a good hitter for a shortstop yet ended up with a below-average OPS+ and wRC+. He was a strong defender who won four Gold Gloves, though he wasn’t regarded highly enough for his fielding to get him into Cooperstown. Six of Baseball-Reference’s nine most-similar players to Rollins are in the Hall, but even his closest statistical comp is fairly attenuated.4 He was the NL MVP in 2007, when he wasn’t the best player on his own team. He held on as a solid contributor for a while, and reaching nearly 2,500 hits is nothing to sneeze at in today’s game. Neither is stealing 470 bases. Is that enough to be the first line on a plaque? Carl Crawford stole 480. José Reyes swiped 517. Still, I’d be happy to see him get in, and this is the year to look for players like that.

Finally, we come to David Wright, whom I previously judged as just below the mark. In his prime, he was the face of baseball, both figuratively and officially. He had eight different seasons good enough to earn All-Star nods or MVP votes (including the year Rollins won, when Wright probably deserved it more) and went back-to-back in both Gold Gloves and Silver Sluggers. His résumé feels light — he has fewer hits (1,777) and home runs (242) than Hunter Pence — and voters have notoriously tough standards for third basemen. Like Pedroia, his career was prematurely derailed by injuries (to his neck, shoulder, and spine). Given their established levels of play leading up to their respective maladies I would argue that an if he’d stayed healthy counterfactual is even more interesting for Wright than Pedroia. It’s a compelling narrative, though it’s still merely hypothetical.

If you’re keeping score at home, that gives us a total of 15 plausible candidates on this year’s ballot. Eight of my 10 votes already locked down, leaving two spots open for seven players: Edwin Encarnación, Gio González, Torii Hunter, Matt Kemp, Dustin Pedroia, Jimmy Rollins, and David Wright.

First I had trouble filling my ballot. Now I face the task of winnowing the field down.

My cases for three of the players above felt more obligatory than enthusiastic. González in service of loosening standards for pitchers, Hunter for his historic collection of hardware, and Kemp for enjoying what was contemporaneously seen as an all-time-great prime season. I am sincere in having reasoned myself into taking their candidacies seriously. But if I’m triaging my votes, they are the easiest cuts.

There are two more names whom I would enjoy voting for, but who in my heart of hearts I can’t say are Hall of Famers: Encarnación and Rollins. Turns out I don’t have room for them after all.

The two men left standing are close enough to the Cooperstown standard that I’d be proud to vote for them. Coincidentally, they are also the names from this group whom I am most confident will get in eventually someday. As Sam Miller would say, I’d rather help them than slow them down.

Beltrán was never punished for his alleged role in the Houston Astros’ sign-stealing scandal. Ditto Pettitte for his admitted use of human growth hormone. Rodríguez was suspended for his role in the Biogenesis doping scandal, but it was not a lifetime ban (he returned and played well afterward), and it would beggar belief to argue that the greatest infielder of all time would not have had a Hall-worthy career without illicit substances.

That Murphy got a first-place MVP in 2016, when he finished outside the National League’s Top 15 in WAR, shows just how rapidly the consensus for player-evaluation methods has changed.

Aside from Alex Gordon, who had a 19.29 ERA in two outings of mop-up work.

The most-similar player to Rollins is Barry Larkin, at an 86 percent match. The only other candidate on the ballot with a more-distant top comp is Alex Rodríguez (82 percent for Willie Mays).

Great ballot, and I fully agree with your reasoning behind voting for the maximum of 10. If guys with statistical and personal profiles like Jeff Kent get in through the era committee anyway, then it's perfectly defensible to support "sub-standard" candidates through the BBWAA.

I'll be very curious to see how your bubble candidates (Wright, Pedroia, Rollins) fare with the electorate again. I expect the vast majority (minus Manny) to receive more support than usual given the dearth of options. How much more is the question.

As a Mets fan, I SO WISH could justify voting for David Wright. Just not enough of a career. If he had like two more years at that peak production? I'd have no choice. Was just too painful to watch him finish his career as a fragile scarecrow.

As for Daniel Murphy, I would feel comfortable leaving him out because he always seemed like an idiot. I still remember one of the Mets pitchers having a big night, and they asked Murphy how many miles per hour that pitcher was throwing and, without irony, he turned and answered, "All of them."