Is the Shift Ban Working?

A reluctant acknowledgment of the promising early evidence

The biggest storylines of Spring Training this year have been the new rules Major League Baseball implemented for the 2023 season, and how they are changing the game. The introduction of a pitch clock to increase pace of play has led to a notable reduction in game lengths. Larger bases have facilitated a spike in stolen bases. Increasingly aggressive baserunners, emboldened by a limit on pre-pitch pickoffs, have inspired a resurgence in catcher back-picks. And of course, the implementation of new limits on on-field behavior are already provoking new methods of gamesmanship.

Amidst the conspicuousness changes caused by these more-visible new rules, there hasn’t been as much focus on what was arguably the most-anticipated and -controversial change the league made this year: Banning the shift.

For the uninitiated, “the shift” is a strategy in which a team puts its fielders in nontraditional places in accordance with where the batter tends to hit the ball. The defending team is essentially betting that they are more likely to turn a would-be hit into an out with unorthodox positioning than they are to let an otherwise-routine play get through the hole where a fielder would normally be. Over the course of a season, a team that bases such decisions off of good data will probably come out ahead. The downside, for both the other team and the fans who like to see hits, is that this leads to less action in the field. There are times when sports leagues truly need to step in to make their on-field product better. Reasonable people can disagree about whether this is one of them.

Modern defensive positioning is far more nuanced than skeptical fans give it credit for; the question coaching staffs and analytics departments have tried to answer is not the binary “Should we use the shift?” but the broader “How do we optimize for outs?” But when you hear “the shift,” you probably think of this alignment, which was popularly used against left-handed pull hitters and is now illegal:

When the ban was announced a few months ago (and as the proposal was batted around the industry in the years prior) I was vociferously against it, as both a fan and an analyst. Contrary to how its detractors bemoan its recent proliferation, the shift has been part of the game for a century. Telling formerly free-floating fielders where to stand on the diamond is conceptually strange. The shift is part of the grand tradition of the ever-evolving balance of baseball as hitters and pitchers discover and counter new advantages. And of course, there’s nothing stopping a frustrated batter from focusing on an all-fields approach that would render the shift irrelevant.1

What’s more, banning the shift wouldn’t make a big difference anyway! Defensive positioning is not a binary. Infielders can still adjust their starting spots to align with a hitter’s tendencies within the confines of the new restrictions. The arms race to find creative loopholes in the rules has already begun. Besides, the empirical impact of the shift ban when implemented elsewhere has been muddled at best.

Well, the early returns are in, and I may have been wrong about that last part.

The most-germane measurement for assessing the effectiveness of banning the shift is batting average on balls in play, better known as BABIP. The stat is exactly what it sounds like: Of all the batted balls that land within the confines of the diamond, how many of them fall for hits? You can basically think of it as batting average that doesn’t count strikeouts or home runs. On an individual level, BABIP is seen as an expression of a batter’s quality of contact (or a pitcher’s ability to induce weak contact), though noisy fluctuations are possible even over hundreds of plate appearances. Across the league, it serves as one measure of the balance between offense and defense. Successful positioning brings BABIP down because more balls in play turn into outs.

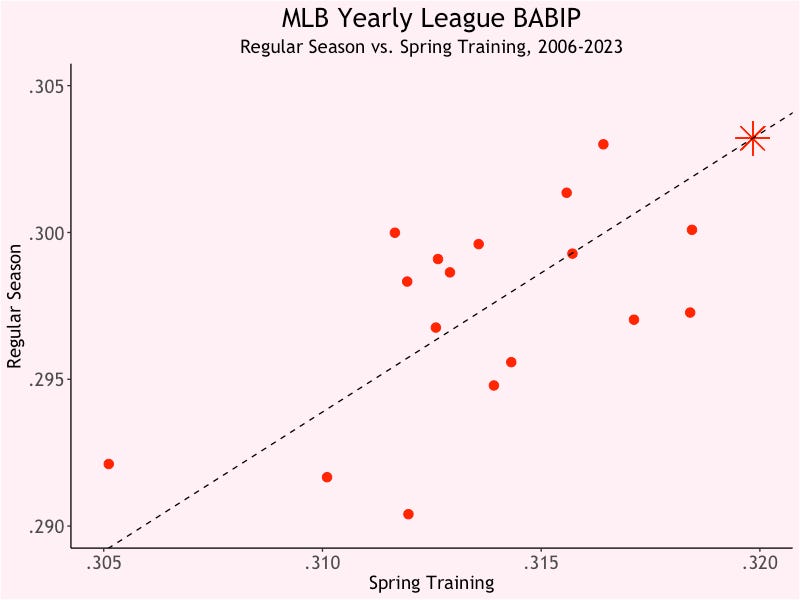

So far in 2023, leaguewide Spring Training BABIP is .320.2 That probably does not mean anything to you without context. So here is some context:

Going back to 2006 — the earliest season for which sufficiently detailed Spring Training stats are easily available — the highest BABIP on record was .318, reached in both 2013 and 2016. This year is on track to comfortably exceed those previous highs. The contrast with the recent past is particularly stark, as the two lowest-BABIP springs on record have come in the last three years. It’s the first time the league average has been above even the recent-historical Spring Training median since 2016.

Does this really matter? Spring Training baseball is very different than normal MLB play. Pitchers are still ramping up to full strength and may be more concerned about regaining feel for their arsenal than getting batters out. You’ll see minor-leaguers with low-quality stuff take the mound in the later innings. Some players are learning new positions in the field, and they may let a ball drop rather than risking an injury with a diving play in an exhibition game.

Even if BABIP weren’t noisy, which it is, it stands to reason that the league baseline would be higher in February and March than June and July. Indeed, the data bears that out. But it turns out you can still tell something about the season to come by how many hits get through the hole in Spring Training:

At the risk of torturing meaning from 17 prior data points, there is a clear correlation between the league’s BABIP in Spring Training and what it goes on to be that summer. Simply shading down a given year’s preseason aggregate BABIP by about 5% explains nearly a third of the variation in how many hits find holes over the next few months. And if we apply that simple linear translation to 2023, the extrapolated regular-season BABIP would be the highest on the chart.

And ever.

The first season for which we have data for sacrifice flies, which are needed to calculate BABIP, is 1954. The .303 BABIP in 2007 is the highest the league has managed in the 69 years since. At the current .320 Spring Training average, if the typical relationship between pre- and regular-season BABIPs holds, the 2023 MLB BABIP will match that. If you go out another decimal point, the forthcoming season is poised to surpass it.

After sitting with these numbers for a while, I wondered if the fact that we have only the earliest games’ data so far could explain the high BABIP. All the factors listed a few paragraphs up about why more balls fall for hits in the preseason apply even more so over the first leg of camp. Frankly, as an anti-anti-shift-er, I was hoping that would give me an excuse to dismiss what we’re seeing. But looking at daily data from the last few years, there’s no apparent pattern of BABIP going down over the course of the spring. If there’s any discernible trend in the clearly noisy dataset, it’s the opposite — BABIP goes up as the calendar turns towards Opening Day.

Last season’s .290 regular-season BABIP was the lowest in 30 years. Holding the rate of balls put into play constant, a baseline increase to .303 translates to about 0.63 additional hits per game. A fan who watches all their team’s games would get about two extra hits to cheer for per week (and two more chances to sigh in frustration as the other teams’ dribblers sneak through the hole). Is that enough to convince someone who thinks baseball is boring to change their tune? I doubt it. But is it enough that a casual fan would notice a difference? It honestly might be. (You can be sure that countless internal models across the league will be retuned, too.)

This is where I concede that the foregoing paragraphs are probably too credulous. It ought to be the first rule of baseball analysis, and really any data science work, to take unexpected results with a grain of salt. Spring Training isn’t even halfway over, and there is plenty of time for league BABIP to regress towards the mean. Less than a fortnight’s worth of exhibition games is hardly enough evidence to refute what we’ve seen in prior experiments. The correlation between pre- and regular-season averages is suggestive, but it's hardly ironclad.

Further, if the BABIP increase is real, the shift ban might not be (the only reason) why. It sounds like the faster pace dictated by the pitch clock takes some getting used to, which could lead to easier pitches to hit or fielders who aren’t as ready to react. I haven’t heard any chatter about the baseball itself changing again this spring, but if we’ve learned anything over the last few years, it’s that you can’t rule that out if the ball is carrying differently off the bat. Perhaps the pendulum of league balance is just swinging back in the hitters’ direction. A relative dip in strikeout rate (23%, still very high by historical standards but the lowest since 2019) and an elevated walk rate (10%) also suggest a generally offense-friendly environment, with the latter in tension with the shift ban as the causal factor.

Even if the shift is the primary driver of a genuinely elevated league BABIP, that doesn’t mean the current equilibrium will hold. Banning the shift encourages batters to the ball in the play by increasing the value of even a weak dribbler relative to a strikeout. Yet the (not always accurate, but not baseless) stereotype of the players who are most vulnerable to defensive positioning — the ones who will benefit most from the new rules, and thus whom teams will increasingly seek out under the new rules — is that they are plodding, all-or-nothing hitters who walk and strike out a lot. In addition, if balls in play become harder to convert into outs, pitchers will have even more reason to pitch away from contact. The recent spike in strikeout rate is in large part because, at the macro level, pitchers have more incentive to optimize than hitters do to avoid them. The new rule dovetails with this trend, and I wouldn’t be surprised if it ultimately leads to fewer balls hit into play.

Finally, if you don’t find any of these nuances convincing enough to temper your optimism about the impact of banning the shift, there’s still the fact that telling fielders where to stand instead of making hitters adjust to a legitimate and longstanding defensive strategy is silly. Surely that principle counts for something.

Yet much as there is reason to be skeptical — as much as I am eager to find reasons to remain pessimistic — the circumstantial evidence is apparent. Batted balls are finding holes this spring at an unprecedented rate. Such fluctuations even in exhibition games have historically been harbingers of the year to come. The leaguewide spike directly corresponds with the implementation of a rule meant to have exactly this effect. Many of us who mourned the loss of unrestricted defensive positioning dismissed the change as window-dressing. It may be time to shift our thinking.

Except of course for how hard it is to do. But so is hitting a 100 mph fastball! No one is proposing banning nasty sliders.

All Spring Training data is through March 8 and courtesy of Bill Petti and Saiem Gilani’s terrific baseballr package.

It's interesting there is a shortstop position. I assume that came into existence very early in baseball history due to the large number of right-handed hitters. To me, the shift is somewhat of a bastardization of the position in that it can be used not only for left-handed hitters, but also for anyone who has a predisposition to hit the ball to the right. The batting average of balls in play is a fascinating stat, one I'm sure the average fan (like myself until I read the incredibly informative Lewsletter) hasn't heard of. I think you bring up a good point about other changes affecting the BABIP (sp?). It makes sense the pitch clock could have an influence. In the end, I think players and coaches will adjust to the rule(s). Thanks for the reluctantly acknowledging the promising early evidence!