Yes, the Shift Ban is Working

Revisiting the new rules' impact at the end of Spring Training

Three weeks ago, as the baseball world started analyzing how Major League Baseball’s new-for-2023 rules were affecting Spring Training play — from games getting shorter thanks to the new pitch clock to limits on pitcher pickoffs leading to a resurgence of catcher back-picks — I sought to investigate whether the restrictions on infield positioning had made a tangible impact on the game. These constraints are intended to create more offense and on-field action by banning a newly popular (though not new) defensive strategy of customizing defensive positioning to where the batter is most likely to hit the ball, popularly known as the shift.1

I am avowed anti-anti-shift-er. I don’t consider it a problem if the pitcher’s team correctly predicts that they should put a fielder in an unorthodox position, but merely the latest salvo in the decades-old give and take between offensive and defensive strategies. Even if it were, I say the solution is for batters to learn to hit it where they ain’t, just as the remedy for a hitter who chases low breaking balls is to work on pitch-recognition, not to ban sliders in the dirt.2 Furthermore, prior implementations of similar rules at lower levels had not necessarily led to appreciable increases in BABIP (batting average on balls in play, or the proportion of batted balls within the confines of the diamond that fall for hits), suggesting that a shift ban might be almost as misguided as an attempt at rebalancing the game as is it conceptually silly to tell fielders who’ve been floating freely for a century where they can and cannot stand.

Yet after analyzing about two weeks’ worth of Spring Training data, I found enough evidence to reluctantly offer some bold claims:

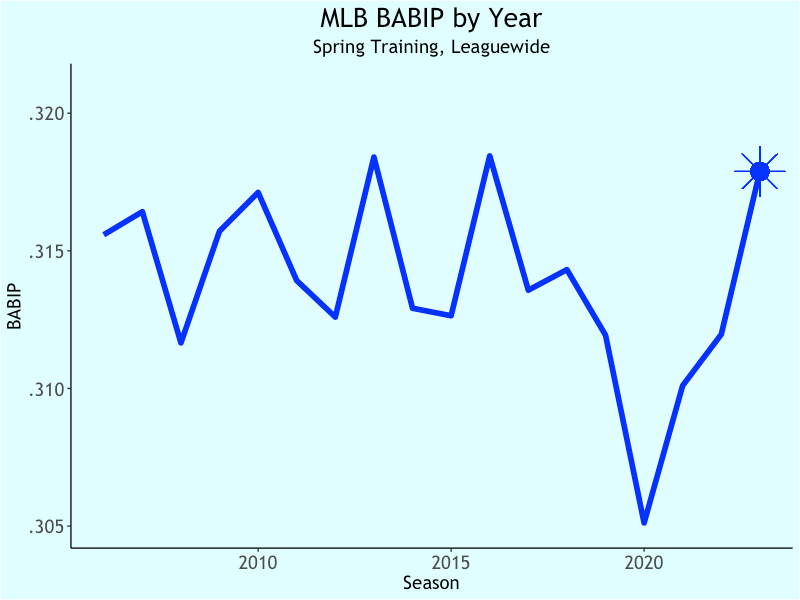

League-average BABIP, the most-common criterion for evaluating a change like this, had spiked to the highest on record in the MLB preseason (.320).

Despite the BABIP baseline being considerably higher in Spring Training, there is at least a clearly suggestive relationship between what the league average is in a given year’s early exhibition games and where it ends up over the summer.

Combining this year’s average with the typical relationship between Spring Training and regular-season BABIPs, the projected increase from 2022 translated to about two extra hits every three games — and the highest MLB seasonal BABIP ever.

I also noted that, while the shift ban was the most-likely suspect for causing such a change, it was possible that one of the other new rules or even random noise was to blame for all the extra hits finding holes.

Tomorrow is Opening Day, which means 2023 Spring Training is in the books. With a few more weeks of data in hand, the magnitude of the positioning rules’ apparent impact looks a little less dramatic than it did three weeks ago. Having said that, we are still on track for a considerable increase in BABIP compared to last year, and I am more confident in pointing to the shift ban as the culprit. Let’s dig in!

A note on Statcast data

The following analysis relies in large part on publicly available Statcast (and Pitch F/X for earlier years) summary data from Baseball Savant. These metrics vary in accuracy over time as the tracking tech has evolved. In addition, not all Spring Training stadiums have Statcast installed, and there is sample bias in which batted balls are able to be tracked. One hopes that these questions of accuracy and representativeness would work themselves out given the high volume of data at the league-aggregate level, but that’s not guaranteed. All data as of morning on March 29.

Where did Spring Training BABIP end up?

At of the end of preseason play on Tuesday night, the league’s baseline BABIP was .318. That’s down from the unprecedented .320 I found at the time of my first article (and the .321 it subsequently climbed to when I checked again a few days later), but it’s tied for the highest Spring Training BABIP since the requisite data becomes easily accessible in 2006, and the largest proportion of balls finding holes since 2016. If you go out another decimal point to .3179, it was still the third-highest year on record.

Based on the typical relationship between Spring Training and regular-season BABIP, my (incredibly oversimplified) model projects a 2023 MLB BABIP of .301. That’s no longer on pace to set the record (as was the case at my first writing), but it’s a rate that’s been exceeded only twice in the 69 years since BABIP’s inputs have been reliably tracked. It would also represent the most balls falling for hits since 2007.

The paltry .290 MLB BABIP in 2022 was the lowest in three decades. Holding the rate of balls put in play constant, an 11-point BABIP increase works out to an extra 0.52 hits per game over last year. An extra seeing-eye single every two days won’t convince someone who thinks baseball is boring to buy season tickets, but that’s a real difference that will lead to an analytically appreciable increase in the run environment.

Could this be part of a general increase in offense?

The shift ban is the most-obvious potential driver of this increased BABIP, but the full package of new rules was designed to boost offense, so we ought to consider other factors too. Rather than looking at BABIP alone, a higher baseline would be consistent with the general balance between run-scoring and -prevention tilting towards batters. However, such an holistic offensive boost did not materialize. This year’s .757 OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage, a quick measurement of offensive skill) fell squarely below the norm from prior Spring Trainings.3 It's a full 21 points below the 2022 preseason and exactly where it was in 2021.

Nor was there a substantial change in other aspects of hitting. The league 23.9% strikeout rate, while down from the Spring Training peak of 24.8% in 2021, was identical to 2022's. The 9.5% walk rate was above the historical norm but below the recent 9.9% high-water mark of 2021. Perhaps most interesting is the meager .165 isolated power (slugging percentage minus batting average, or extra bases per at-bat), the lowest since 2015. In addition to being at least conceptually related as a measure of batted-ball quality — hold that thought — league ISO definitionally increases along with BABIP, so it's interesting that the former was down while the latter was up.4

Has pitching been worse?

While there isn’t much practical difference between hitters getting better and pitchers getting worse, flipping our perspective might help identify some underlying changes. Pitchers who are still getting used to the new pitch-clock system might be uncomfortable, and thus more prone to mistakes. Limiting the recovery time between pitches could also mean they don’t throw as hard. Or maybe the interruption of the World Baseball Classic diverted more innings to lower-quality minor-league arms.

However, from the thousand-foot view, I don't see any sign of inhibited pitching.5 The 7.7% rate of meatball dead-center pitches — defined as being in both the horizontal and vertical middle of the plate — was in line with recent Spring Training norms, and better than the 8.1% high-water mark in 2022. Fastball velocity remained within a fraction of a tick of its recent peaks regardless of how you categorize them.

Are batters hitting the ball harder?

Even if overall offense hasn’t been invigorated this spring, batters could have been putting more of a charge into the ball when they made contact and thus getting more hits. Yet there’s no real evidence of that either. The Spring Training 88.0 mph average exit velocity on non-bunt balls in play was the lowest on record, and the 148-foot mean projected distance was tied for least in the eight years with substantial data-tracking. While the 4.5% rate of home runs is high by historical standards, it was the lowest since 2017 and significantly down from its 5.5% peak from a year ago.

Of particular interest is the juxtaposition between this decreased home run rate and the concurrent, lower-than-usual prevalence of doubles and triples relative to singles — i.e., how many non-homer hits went for extra bases. This spring’s 27.0% inside-the-park-XBH rate was the lowest since 2015. That’s counterintuitive, because a just-missed home run probably doesn’t become for a single. A fly ball that would have left the yard but for an unlucky breeze or a less-bouncy ball typically either caroms off the wall for extra bases or falls into an outfielder’s mitt. If BABIP is up despite more fly balls becoming catchable and in-play extra-base hits are down even though more big hits are staying in the park, something must be balancing that out by funneling a different source of would-be outs into singles. Perhaps there was a recent rule change that led to an influx of bloop hits?

Three weeks later, I’ll cool down my rhetoric: We are no longer on pace for the highest BABIP ever.6 Further, even if we do see an extra hit every two games in 2023, that might not be the final state of the post-shift-ban equilibrium. If all-or-nothing sluggers are disproportionate beneficiaries of the new defensive limitations, they will become more valuable relative to their all-fields-approach peers, leading to less action in the field.7 In addition, limiting contact of any sort will become even more important for pitchers, which could fuel a further increase in strikeout rates and decrease the number of balls in play.

Having said that, I expect to see a meaningful increase in BABIP this season to an extent that even a casual fan might independently notice more balls finding holes, and I’m running out of reasons to doubt the obvious explanation for why. Maybe it’s capricious to suddenly outlaw a hundred-year-old tactic that’s neither unsafe nor immoral. Perhaps it’s silly to interrupt the eternal strategic dance between hitters and pitchers for an aesthetic change that may well backfire in the long run. You can even say the Commissioner’s Office’s perception of what fans care sounds like it comes from credulously listening to sports talk radio. Still, the shift ban is working, and like a short line drive to right field under the new rules, there’s nothing we can do stop it.

Specifically, the rules mandate that the infielders must be standing on the infield dirt and divided evenly on either side of second base.

If the shift had really become such a menace to the modern game, why haven’t we seen player development departments across the league pivot to prioritizing an all-fields approach so that subsequent generations of hitters could counter it?

Or is it Springs Training?

While ISO is commonly understood as a measure of power production independent of a player’s other offensive attributes, every would-be out that falls for a hit has a chance to go for extra bases and thus increase the numerator without adding to the denominator (at-bats).

We should acknowledge the possibility that a more-nuanced analysis based on something like Stuff+ might show different results.

Though it’s not out of the question!

The additional rules encouraging baserunning may mitigate this perverse incentive.

I was a fan of the shift ban simply for the reason that reliance on true outcome metrics had made someone like Adam Dunn more valuable than someone like Tony Gwynn. Huh? Baseball created the monster of metrics when they really didn't need it. I'm looking at the ban like football moving the hashmarks towards the center of the field to open up the passing game. Can't wait to see if the rule changes get the desired effects over the course of the season.But the game was fine for 100 years before enhanced metrics, creating paralysis by analysis.