Unpacking the 2025 Baseball Hall of Fame Results

Six takeaways from this year's Cooperstown inductees and voting trends

The results are in, and the Baseball Writers Association of America has elected three new members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Ichiro Suzuki, CC Sabathia, and Billy Wagner all cleared the 75 percent threshold for selection, and will join Eras Committee picks Dick Allen and Dave Parker to be inducted in Cooperstown this summer.

As we celebrate some of the greatest players in the history of this great game, here are six takeaways about the present and future of the Hall of Fame selection process.

Celebrating a phenomenal Hall of Fame class

Ichiro Suzuki was the kind of player who could make you fall in love with baseball. From his signature speed and contact skill to his fierce training regimen to his legendary profanity-laden pregame speeches, he was truly a one-of-a-kind player. With all due respect to Shohei Ohtani, Ichiro is the closest any MLB player of my lifetime has come to how mid-aughts memers talked about Chuck Norris. It’s a shame that one anonymous voter denied him unanimty.

The greatest workhorse of his generation, a noted philanthropist, and an athlete who has overcome immense personal adversity, CC Sabathia was known throughout his career as both a bona fide ace and one of the game’s best people. Heading into the Cooperstown voting season, I didn’t think he would get in, at least not on his first ballot. I am thrilled to have been proven wrong.

Last but not least is Billy Wagner. I’ve written at length about Wagner’s candidacy multiple times. He is arguably the second-best reliever in the history of baseball, and on a pitch-by-pitch basis his may be the most-dominant arm the game has ever seen. He has been particularly open about how much this honor means to him and how disappointed he has been by his previous snubs, including missing induction by a mere five votes a year ago. Congratulations to him on a sadly belated but well deserved achievement.

…and lamenting some one-and-done candidates

There were nine first-time-eligible players on this year’s BBWAA ballot whom I believed deserved at least serious consideration for Cooperstown. Sabathia and Suzuki are in. Félix Hernández and Dustin Pedroia will remain in consideration for 2026. The others failed to reach the requisite five percent to stay on the ballot, so their paths to enshrinement is all but closed. (As Sam Miller noted in his ballot explainer, the nature of the selection process means no one is ever officially rejected, but one-and-doners from the writers’ elections tend not to be priority considerations for subsequent Eras Committees.)

This quintet of snubs is headlined by Russell Martin and Brian McCann, two catchers with seemingly underwhelming career numbers but who ranked among the elite pitch-framers of their generation, if not of all time. MLB teams place immense value on stealing strikes; the league clearly sanctions it despite the ethical concerns it raises. I had hoped a critical mass of voters would think about how much they’re going to care about catcher defense when Yadier Molina debuts on the ballot 2028, and apply that same logic to Martin and McCann. They were longshots to get in, but it’s a shame they didn’t get at least another year for their cases to percolate.

Ian Kinsler and Troy Tulowitzki were both in my honorable-mentions group — not quite good enough (Kinsler) for long enough (Tulowitzki) to compete for one of my 10 (hypothetical) votes this year, but close enough to the line where I could see myself being swayed in the future. Unfortunately I won’t get that chance.

Finally, there’s Ben Zobrist. I’m not going to tell you that his numbers come remotely close to the Hall of Fame standard. Yet he was the sport’s first super-utility star, and he had an enormous impact on modern strategy by making positional versatility cool. I thought that made him Cooperstown-worthy. Evidently not a single BBWAA voter agrees.

This was an exceptionally deep group of first-year-eligibles — if you account for Martin and McCann’s framing value, the 10 newbies with a JAWS score of 40 or higher are the most since 1948 — so it was inevitable that some worthy candidates would get lost in the shuffle. I hope they get the consideration they deserve from some future committee.

Get used to the holdovers

Fifteen players finished below the 75 percent threshold for induction yet above the 5 percent minimum to remain on the ballot. With no one falling off for exhausting their eligibility window — Wagner was the only tenth-try candidate this year — each will get another shot next year. It’s a strong group, as I think 12 of them had Hall-worthy careers, and the exceptions (Torii Hunter, Jimmy Rollins, and David Wright) are close enough that I wouldn’t want to be the reason why they fell short. Hopefully you’re not sick of hearing about them, because this is effectively the group we’ll be discussing for the next few years.

Looking ahead to 2026, Cole Hamels is the only new player whom I expect to get more than a handful of courtesy votes. (There’s an interesting contrarian case to be made for Ryan Braun, but it won’t find a sympathetic audience.) The 2027 first-year class is similarly shallow, with virtual-lock Buster Posey and maybe Jon Lester (more on him in a moment) as the only serious candidates. So for the most part, the debates we had this year will be the same ones we’ll have for the next two cycles.

The good news is, this reprieve from the recent fire hose of quality candidates will give the holdovers the chance to consolidate support. Carlos Beltrán, who missed election by just five percent of the vote today, can clear his calendar for Induction Weekend 2026. Chase Utley has an open lane as he heads into next year as both the best player and most-voted-for holdover on the ballot without character-clause questions attached to him. (The only player to earn at least as much support as Utley’s 40 percent on their second try who hasn’t gotten in eventually is Beltrán.) Hernández has time to build on the solid 21 percent he earned in 2025, and Andy Pettitte (who doubled his support from 14 percent in 2024 to 28 percent this time around) will look to keep his momentum going. It would be great to clear the slate, or at least get some deserving candidates on clear paths, ahead of the strong classes coming in 2028 (featuring Albert Pujols, Robinson Canó, and Molina) and 2029 (headlined by Miguel Cabrera, Zack Greinke, and Joey Votto).

Pitching standards starting to change?

The following statement will read like a complaint, but I mean it as a good thing: CC Sabathia is the worst starting pitcher the BBWAA has elected in my lifetime. Seriously. Tom Seaver gave his acceptance speech a few days before I was born. Here is a complete list of pitchers who made a majority of their appearances as starters and were selected by the writers since then:

Bert Blyleven

Steve Carlton

Tom Glavine

Roy Halladay

Randy Johnson

Greg Maddux

Pedro Martinez

Mike Mussina

Phil Niekro

Nolan Ryan

John Smoltz

Don Sutton

Lesser pitchers have gotten in in the past or via the Veterans Committee, but the BBWAA’s recent standards have been incredibly high. I would argue that, given how the league has changed and pitching strategies have evolved, they have been impossibly high for modern starters. It took Mussina six elections to get in. Blyleven had to wait until his 14th try. Kevin Brown, David Cone, and Rick Reuschel were one-and-dones. There ended up to be good reasons not to vote for Curt Schilling, but I’ll never understand why he wasn’t an easy yes before that.

Sabathia getting in on his first ballot with a resounding 87 percent of the vote feels like the writers planting a flag to modernize their standards. The bar is still high, mind you — Sabathia was really good! — then perhaps so can Hernández, who did better than I expected in his debut election, or Mark Buehrle and Pettitte, who have spent years languishing at the bottom of the ballot. Hamels and Lester will be good test cases for this in the next couple years, followed by now-more-interesting names like Corey Kluber, David Price, Stephen Strasburg, and Adam Wainwright.

Continued silence on partner violence

Andruw Jones stands on the precipice of immortality. With nearly two thirds of the vote in his pocket and less competition on the horizon over the next two years, he is very likely to earn election before his eligibility expires in 2027; the only candidates to reach 66 percent and not eventually get in somehow are Schilling and Barry Bonds. As one of the most-dynamic players of his generation and arguably the best defensive outfielder of all time, his on-field achievements are clearly worthy of Cooperstown. As a person who was arrested for and pled guilty after a brutal incident of domestic violence, it’s important to consider the larger implications of celebrating him.

Maybe it’s naïve — especially this week — to expect voters to consider partner violence when they cast their ballots. That doesn’t mean they shouldn’t.

The Hall of Fame is not a preordained force of nature. It is what we make it. There is both official guidance and established precedent for considering candidates as people, not just as stat lines. There are much better players than Jones whose busts are absent due to far less societally harmful violations of Cooperstown’s character clause. Yet while it’s become de rigueur for writers to explain their positions on dopers one way or the other, most ballot reveals don’t mention domestic violence at all. Only a handful of voters have named Jones’ arrest as why they do not support him. Particularly vexing are the dozens of writers who stopped voting for Omar Vizquel after he was accused of assault, yet continue to check the box for Jones.

This issue is bigger than Jones. It’s about Ramírez, Vizquel, and Francisco Rodríguez, who are also on this year’s ballot (though stand little chance of getting in). It’s about Miguel Cabrera when his time comes in a few years. It’s about Trevor Bauer, who has said that the sport’s selective tolerance for such acts gives him hope of returning to the Majors. It’s about people who have experienced partner violence seeing an abuser soak in the applause at the induction ceremony, the adulation blurring the lines between his athletic accomplishments and his personal character. That means more than making the Plaque Gallery a slightly less incomplete curation of the sport’s biggest stars.

For the folks reading this who voted for Jones, I understand your mindset. I used to believe in compartmentalizing personal conduct from Cooperstown conversations. It’s not too late to change your mind. I hope you will reconsider next year.

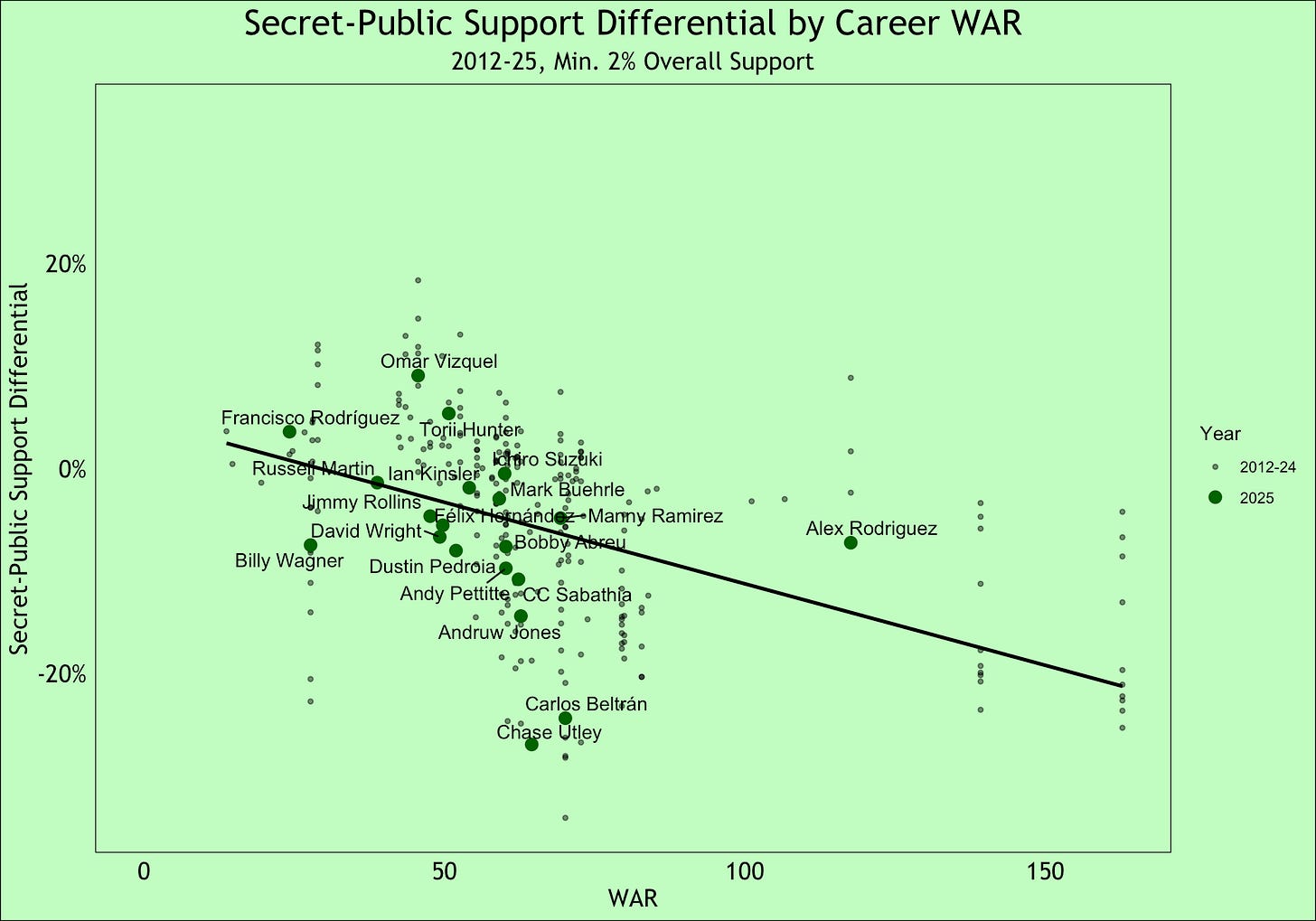

Secret ballots strike again

I’ve been tracking the impact of secret ballots on the Hall of Fame selection process for more than a decade — including a longitudinal study demonstrating this persistent trend. Voting for Cooperstown is not a right but a privilege, reserved for a specifically selected cohort of journalists with extensive experience in both analyzing baseball and communicating their knowledge to the masses. In other words, every voting member of the BBWAA should be more than capable of explaining their choices. Not to mention the conflict of interest of writers not disclosing their own roles in the news they help create.

In fact the association has voted to make their ballots public multiple times, only to be overruled by the Hall of Fame itself. So the fact that writers who choose not to unveil their ballots vote not just differently but worse is troubling. And this trend has continued in 2025.

Based on the counts from publicly revealed ballots as of a few minutes before the results were announced — as dutifully tracked by Ryan Thibadoux, Anthony Calamis, and Adam Dore — there are some conspicuous differences with the official results:

Only one voter declined to vote for Ichiro. Whoever denied him the honor of a unanimous did not put their name on it, knowing that snubbing him is indefensible.

Carlos Beltrán would have sailed into Cooperstown had everyone voted like the public voters, who named him on 82 percent of their ballots. He got just 58 percent support from anonymous writers.

The candidate who benefited the most from secret voting relative to public ballots? Omar Vizquel, whose support falls from 22 percent to 13 percent when writers put their names on their picks, and who also happened to be the most shameful choice among this year’s candidates.

While correlation is not causation, there is a clear connection between players’ skills and their public-private vote differentials. You can see how this year fits into the historical trends, whether you measure players’ deservingness by WAR:

Or by JAWS:

Or, most damningly, by how worthy the candidates are according to the voters themselves:

Each of the top 12 finishers in this year’s voting lost support from voters who did not put their names on their picks. Coincidence or not, the fact that this keeps happening is a very bad look. Voting for the Hall of Fame is a privilege, not a right. If you are an experienced journalist with a history of covering baseball and communicating information to an interested public and you cannot satisfactorily explain your choices to your readers, you voted wrong.