How Much Would MLB's Best Swing-Off Hitter Be Worth?

Estimating the value of elite home run derby skill under the proposed new rules

The swing-off is the talk of baseball. The mini-home-run-derby conclusion to last week’s All-Star Game made for one of the most-thrilling Midsummer Classic moments of my lifetime. Yes, it was gimmicky. But it was fun! In the way that baseball should be. As someone who was initially skeptical of the idea — back in my day, a tiebreaker meant playing honest-to-goodness baseball until one team won — I must admit it was a blast to watch. Even more so than the previous night’s actual Home Run Derby, which is overdue for some major format tweaks.

So popular was the swing-off that there is (early, speculative, trial-balloon-esque) discussion about implementing the sudden-death swing-off in the regular season, too. And since the current extra-innings rules (in which each team starts each frame with a Manfred Man on second base) mean that both inauthenticity and undermining the league's stated desire to reinforce the value of starting pitchers are already sunk costs, the idea has grown on me. If adherence to the long-established rhythm of how runs are scored is no longer the first principle, then we may as well make MLB’s overtime structure as entertaining as possible.1

It isn’t going to happen. Not anytime soon, anyway. The Commissioner’s Office usually telegraphs such rule changes years before they are implemented. Removing the veneer of authenticity from extra innings would be a particularly tough sell, even if it’s now a question of degrees more than principle.

But what if it did?

The other day, a friend posed one of the best sports hypotheticals I’ve heard in a long time: In a world where the swing-off fully replaced extra innings, how valuable would the best overtime-homer-hitter be?2 Once I started chewing on the question, my mind wouldn’t let it rest. I’ve been tossing and turning at night, arguing with myself about whether or not a team would rush out to sign someone like Joey Gallo, who has prodigious power but makes unplayably infrequent contact, as a swing-off ringer.3 So I decided to try to figure it out.

The first question in developing a framework for swing-off value sounds basic but requires some thought: What are the odds that a good hitter who’s trying to hit a homer will hit a lobbed pitch over the fence? The answer is probably lower than you think. It feels like Aaron Judge or Shohei Ohtani could do it on command. But if you watch a big-leaguer take batting practice, you’ll see a number of towering fly balls die well short of the warning track. (Which then makes you appreciate how hard their job is when the pitcher is trying to get them out.)

There are two recent datasets for estimating how frequently a batter will homer in what is essentially a competitive-BP setting. The first was the All-Star Game swing-off itself. In the prototype demo for these potential new rules, the five participating players combined to swat seven dingers over 15 swings.

The second was the Home Run Derby the night before. The main portion of each round, in which the goal is to hit as many homers as you can within three minutes or 40 pitches (so players are incentivized to swing at suboptimal pitches), was fundamentally different than the swing-off, where hitters have unlimited time and pitches but must be choosy with their cuts. However, the outs-based bonus period, adapting the pre-2015 Derby format in which contestants were limited solely by the number of non-homer hacks they take, presented an effectively identical challenge: swing at only the pitches you are most confident that you can clobber. Boxscore-like data for the Derby proved surprisingly difficult to find, so I rewatched each bonus round and counted 30 total taters on a combined 78 swings.

Combine this year’s All-Star Game and Derby data and you get 37 homers on 93 hacks, for a dinger-per-swing rate — which I will henceforth refer to as “dinger rate” — of 40 percent. It turns out this is a stable baseline. From 2005 to 2014, the last 10 years in which the Derby was out- instead of time-based, the dinger rate held steady between 35 and 44 percent.

Is a 40 percent dinger rate a fair assumption for swing-offs? A skeptic could say that the baseline from the Home Run Derby, featuring eight of the top sluggers from around the league, is too lofty an expectation for a regular-season swing-off, where participation would expand to the third-best power hitter on each team. On the other hand, stars who sit out the annual skills contest (at least eight hitters are known to have declined invites this year, including Judge and Ohtani4) would presumably participate if an actual game were on the line. Hitters would also be fresher over the course of three swings than while taking dozens of hacks in quick succession (as in the Derby), and could train for it more consistently throughout the season. The fact that you can argue the benchmark from both sides, along with its consistency as an equilibrium point over time, tells me we are in the right ballpark (pun fully intended).

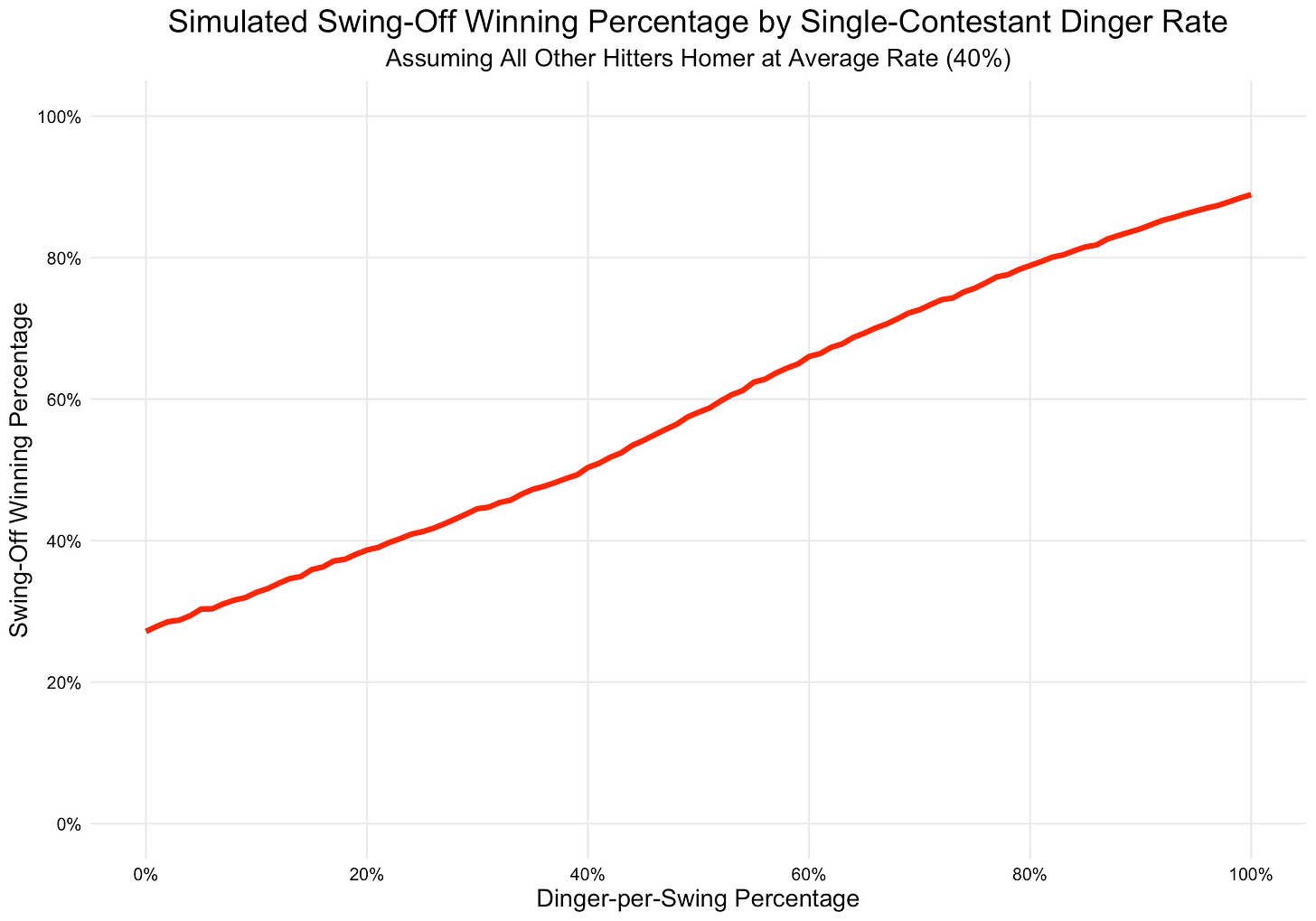

Using 40 percent as our baseline, I set out to model the impact of a single player’s dinger rate on their team’s odds of winning a swing-off. I wrote some quick derby-simulation code that assumed five of the six participants had 40 percent odds of homering on each of their three respective swings, while the sixth contestant’s chances could vary. For each integer value p between 0 and 100, I ran 100,000 swing-off simulations where the final batter had a dinger rate of p percent. If the teams tied after nine swings, our variable player took the subsequent sudden-death round(s) when they were an above-average slugger (p > 40), and a teammate stepped in otherwise.

Here’s how the team’s winning percentage varies along with a single contestant’s skill:

When one of a team’s three swing-off contestants was physically incapable of hitting the ball over the fence (p = 0), they won 27 percent of the time. After nine swings they were behind in 64 percent of simulations, ahead in 19 percent, and tied in 17 percent (which became coin-flips as two assumed-average hitters faced off until they reached a decisive result). By contrast, if a hitter were guaranteed to homer on every swing (p = 100), they would lead their team to victory in 89 percent of mini-derbies. They won outright in 75 percent of simulations, lost in just 11 percent, and went to additional rounds in 14 percent (in which case the invincible contestant always eventually came out on top). You may note that the line gets a little steeper just past the 40 percent baseline. That’s the impact of having an above-average contestant in both the initial round and potential tiebreakers.

Over the last two seasons (after the schedule disruptions from COVID and the lockout subsided), nine percent of MLB games went to extra innings, so teams averaged about 14 end-of-regulation ties per year. At that frequency, the absolute maximum range for the expected impact of swing-off skill — the 62-point gap in win expectancy between me and Sylvester Coddmeyer III — is 8.6 wins per year. For those not versed in contemporary player-evaluation methods, that is enormous. Most years, a hitter who was worth more than eight wins would be a frontrunner for the MVP.

Yet that exaggerates the realistic range of skills at a team’s disposal. There is no Homer Simpson with his Wonderbat whom you can count on to go yard on every swing, and no manager would be short-handed enough to tap Homer Simpson without his Wonderbat for a sudden-death mini-derby. To come up with a less-reductive answer, we must estimate a more-plausible distribution of leaguewide dinger rates.

Returning to the historical Home Run Derby data, Bobby Abreu’s 41 big flies in 2005 were the record under the previous, outs-based rules. He homered on 58 percent of his swings. The highest dinger rate in a night was Josh Hamilton’s 59 percent in 2008. From those observed maxima I would infer that the plausible sustainable upper limit for taters per swing is around 60 percent.

Based on the simulations above, inserting a slugger who goes yard on 60 percent of their hacks into an otherwise-average swing-off raises their team’s win probability from 50 percent to 66 percent. Given a typical number of would-be extra-inning games, this would peg the value of the best swing-off hitter in baseball at 2.2 wins above average per year.

That isn’t quite the final answer. A core tenet of modern sports analysis is that average is often the wrong comparison point. Everyday players don’t grow on trees. A full season’s worth of league-average production is a very valuable use of a roster spot. Rather, the relevant benchmark is how much better a given player is than whoever would take the team’s third swing-off spot if a vacancy arose.

It’s an especially interesting consideration here, where the average swing-off participant would be better than the average MLB hitter. In most cases, “replacement level” — the common (if impolitic from a labor-relations perspective) term for the performance you’d expect from a short-notice substitute — is equivalent to a waiver claim or Triple-A call-up. Here the replacement level would be defined by the fourth-best BP hitter on each team. A replacement-level slugger in the swing-off context could paradoxically still be expected to have above-average power.

At this point we can triangulate a rough estimated distribution of swing-off value given how the bell curves for other MLB skills are shaped. Unintentionally but very conveniently, the benchmarks we have already established map linearly to the 20-80 scale, a grading system common among baseball scouts in which 50 is the Major League average and 10 points of difference correspond to one standard deviation of skill. If a 60 percent dinger rate indicated a generation-defining talent (scouting grade: 80), 40 percent were the sign of an All-Star candidate (60), and a player who had zero chance of clearing the wall represented the lower limit for a plausible MLB player’s skill (20), that implies that the expected swing-off dinger rate for league-average hitters (50) is around 30 percent.

Given that estimated distribution of BP prowess and assuming that the typical backup derby contestant would have somewhere between average and plus raw power (a 55 on the scouting scale), we can calculate a replacement-level dinger rate of 35 percent, and a 47 percent chance of such a player’s team winning a swing-off if all the other hitters involved were average. That’s a 19-point difference in simulated win probability between a top-of-the-scale slugger and their likely backup. Translating that to WAR terms means we could reasonably expect the best swing-off hitter in baseball to be worth 2.6 wins a season beyond what they contributed during the actual games, for which the free-agent value (based on the commonly assumed price of $8 million per win) would be around $21 million a year.

With the crucial caveat that WAR is often described as an ill-fitting framework for evaluating relievers: the range of outcomes for swing-off sluggers would be similar to that of MLB bullpen arms, with the best derby ringer in the league contributing about as much WAR value as an elite closer.

As the initial shock from the major sport with the strongest commitment to consistent gameflow declaring that hundreds of matchups per year would end in a gimmick wore off, the baseball metagame would evolve quickly. Starting pitching would be further deemphasized, as capping the innings a team may need to cover at nine would give managers free rein to go to their bullpens even earlier. That, like banning the shift, would make strikeout rates go up. So would giving teams even more incentive to prioritize power over contact skill in evaluating players. Routine pregame BP would both feel more important as training for the swing-offs and be tracked more closely as tryouts for the tiebreakers. And as has happened lately for highly reputed managers and front-office leaders, the coaches who throw the best BP might become hot commodities around the league.

But the biggest change would be creating a new dimension for players to create value. A league-average player will be worth around two wins above replacement over 162 games. A hitter who’s merely sufficiently good at (what we now think of as) batting practice could conceivably exceed that by taking three swings every two weeks. And while the odds of making such an impact would be largely contingent on factors beyond their control (like how many taters their teammates hit), there could be even more upside if the stars align — like if they played for last year’s Boston Red Sox, who went to extra innings 20 times instead of our assumed 14.

Whom that applies to, I’m not sure. The Home Run Derby is famously unpredictable, with no clear common traits that separate the winners from the other prolific-slugger contestants. Maybe an established superstar like Judge or Ohtani finds yet another skill that they are the best at, and the price tags for truly elite hitters soar even higher. Maybe it helps all-or-nothing big-swingers like Gallo and Mark Reynolds retain value after their hit tools decline to heretofore-unplayable levels. Or maybe there’s some Quad-A player out there who can’t recognize quality spin and whose name fans don’t know yet, waiting for the day when being dinged for having “five o’clock power” turns out to have a silver lining.

You can bet that teams would start trying to find their designated derby contestants within five minutes of the league signaling that these new rules were a real possibility. And with that much impact at stake, they would swing for the fences in the endeavor. The league’s top swing-off sluggers could command eight figures in (additional) salary on the open market and legitimate prospects at the trade deadline. Ringers whose best skill is taking BP would replace all-around-better players for bench spots on playoff rosters. It would open up a new paradigm of on-field value, and the players who can prove themselves at it will knock it out of the park.

It is important to consider that the choice here is not between the swing-off and old-fashioned extra innings, but between the mini-derby and the already-bastardized status quo.

While there is room for compromise solutions here — I liked a suggestion of playing three unadulterated extra innings (sans the default runner), then going to a mini-derby if a tie persists after the 12th — for the purposes of this post I assume the swing-offs start immediately after the ninth inning.

Gallo is now converting to pitching, and I’m fascinated by the idea of a team signing him for the niche two-way role of mop-up reliever and designated swing-off hitter.

Ohtani said he would be more inclined to participate if the event were focused on distance — a nice validation of my proposal to reorient the Derby around hitting the longest moonshot.