Why Do Cheesesteaks Outside Philadelphia Suck?

Three explanations for the Delaware Valley's sandwich superiority

National Cheesesteak Day is a grand oxymoron. If you live in the Philadelphia metropolitan area, today is among the holiest days on the calendar. Otherwise? You don’t have much to celebrate.

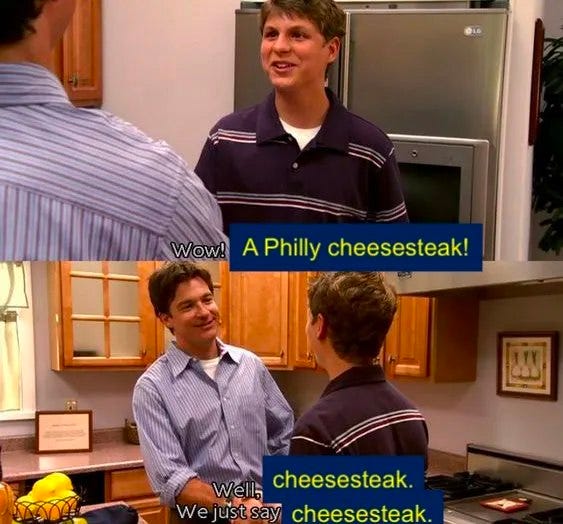

Moving to South Philly as an adult instilled in me a particular appreciation for cheesesteaks. Growing up in Ohio, I liked cheesesteaks, or at least I thought I did. A vaguely melty beef and cheese sandwich, even the suburban-mall food-court version, is usually pretty tasty. Then I moved to Pennsylvania, and my eyes were opened as when Plato’s shadow-watcher stepped out of the cave. Even a mediocre steak in Philadelphia, like those at the tourist traps of Pat’s and Geno’s, was so much better than any other I’d had before.

Cheesesteaks helped me learn my adopted home. I would hear of an intriguing new-to-me deli and use it as an excuse to visit a different part of the city. In my eight years in the Delaware Valley, I ultimately tried over 50 different steaks. I devoted countless hours and cholesterol to fine-tuning my Top 10 list. I even got to call myself a Professional Cheesesteak Writer.

My cheesesteak intake has precipitously declined in both quality and quantity since my wife and I moved to Rhode Island last year. I knew this reckoning was coming, but now that I’ve seen the light it’s been hard to be back in the shadows. So over the last few months I’ve spent a lot of time pondering why it’s so hard to find a quality cheesesteak anywhere else in the world.

Here are the three theories I’ve come up with for why other places’ cheesesteaks suck. If you’re a Philadelphian, I ask you to help spread the good word so that others may know the joys you take for granted. And if you’ve never had an authentic cheesesteak, these are some reasons — on top of the many I’ve offered in the past — to make a pilgrimage and try the real thing.

1. The bread is wrong

This may sound silly. Everywhere has bread! But it’s by far the most common culinary complaint I’ve heard from fellow Philly ex-pats. I liken it to the cliché New York snobbery about bagels, especially because the ideal characteristics of a hoagie roll are similar to those of a bagel. (Ironically, it is surprisingly hard to find a good bagel in Pennsylvania.) In South Philly, the names adorned on famous bakeries, like Amoroso and Sarcone, are as beloved as those of Utley and Kelce.

The most distinctive feature of good hoagie bread is the texture. It should be spongey with some give on the inside, like the seat of a well-worn couch. It needs enough structural integrity to hold together when it’s stuffed with meat and grease, and a crust that’s chewy but not crispy. It’s a Goldilocks zone that doesn’t really exist outside the Delaware Valley. Sub rolls are too squishy and fall apart while you’re eating them. Baguettes or crusty Italian loafs dominate the mouthfeel with their crunch. A lightly toasted soft roll can approximate the right texture in the aggregate, but you lose the wonderful contrast of the juice-soaked innards and the slight bite of the crust.

Flavor is also a balancing act. The bread should be innately tasty enough to enjoy it on its own, so even a particularly bready bite is not bland. Yet a too-flavorful roll can disrupt the balance of the cheesesteak. I find that the taste of sourdough clashes with the taste of the ribeye. A little sprinkle of seeds is a nice accoutrement; a dominant sesame flavor is more befitting of a chicken cutlet or roast pork. (This is one of the reasons why I don’t get the hype around Angelo’s, probably Philly’s most-beloved steak shop — their heavily seeded homemade rolls are delicious, but they pairs better with their meatball parm.)

It’s no coincidence that the most-authentic cheesesteak I’ve had outside the Delaware Valley is served on the best roll. Julie and Dean Couchey, who used to live in Philly and now run the popup shop Jawn’s here in Rhode Island, tried nearly a dozen different rolls in their search for the right combination of softness and strength. (Their favorite from their time in Pennsylvania was Liscio’s.) The winning roll is sourced from a bakery in New York. “Other customers definitely remarked on the bread, about how they liked it and made for a great sandwich,” Julie told me. “But the Philadelphians definitely made it known when they were comparing it to their local spot!”

2. No one uses whiz

I’m not here to defend the integrity of Cheez Whiz as a product. Just reading the name of the product may have triggered your gag reflex. Even the family that runs Pat’s King of Steaks, where whiz was popularized as a cheesesteak topping, concedes that they started selling it out of convenience, not taste.

Yet whiz became the standard in Philadelphia for a reason. It’s actually really good on a cheesesteak, where having enough salty sharpness to stand up to the ribeye is more important than, say, whether it’s actually cheese. More importantly, its viscous liquid state allows it to coat every nook and cranny of the meat inside the sandwich. It even soaks into the bread, which solid cheese cannot do without first melding with the steak grease.

Have you ever found that kind of ubiquitous gooeyness on a cheesesteak outside the Delaware Valley?

You don’t need whiz to get that level of all-encompassing cheesiness. The best places can effectively mix and melt normal sliced cheese into the ribeye — ideally Cooper Sharp American — but it’s harder to do. (Even in Philly, not every deli makes the effort.) However, I’d argue that whiz’ presence in the zeitgeist is key to establishing a common understanding of how cheesy a cheesesteak ought to be.

Most sandwich shops outside Philadelphia don’t have the guts to offer whiz. As a result, there’s no broader awareness that the cheese ought to seep into every bit of the sandwich, and diners don’t understand what they’re missing when they’re served a couple slices lazily melted on top.

3. It gets overcomplicated

There are four standard ingredients to a cheesesteak: a roll, griddled ribeye, American(-like) or provolone cheese, and optional fried onions. That’s it. Compare that to how menus in other places list a “Philly” (this terminology alone is a guaranteed sign of inauthenticity).

A “Philly” served elsewhere usually comes with mushrooms (an acceptable addition in the Delaware Valley, but not the standard) and chopped bell peppers (uncommon at a real steak shop). They may substitute a fancier cheese like pepper jack (used only occasionally for specific spicy-steak specials) or Swiss (an explicit violation of the Cheesesteak Commandments). And god help you if you walk into a store in South Philly and ask for a steak with mayo.

So where did expectations of peppers and Swiss come from? I suspect they were added because it’s easier to make a sandwich feel distinctive with more toppings than by nailing the techniques that make a few basic ingredients shine: The perfect color on the ribeye, the sweet kiss of soft onions, the salty creamy cheesy goo that melds with the meat juices and seeps into the bread. Skimp on the execution and it’s just a boring old beef and cheese.

The extra accoutrements aren’t just unnecessary. They upset the elegant simplicity of the dish. What’s more, they distract from the task of balancing of humble ingredients, which is what makes a cheesesteak truly special. Deemphasizing the basics turns one of the greatest culinary pleasures known to mankind into just another sandwich.